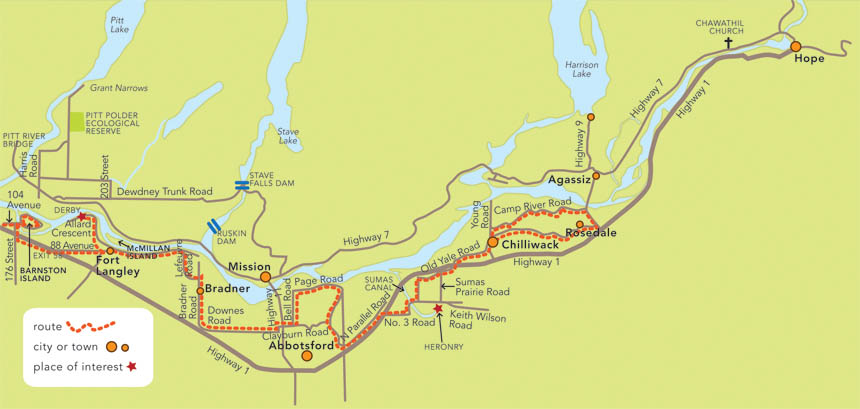

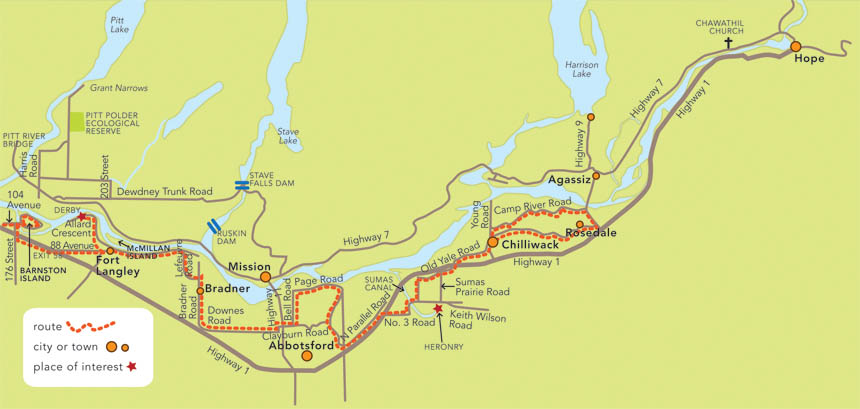

Fraser Valley Slow Roads

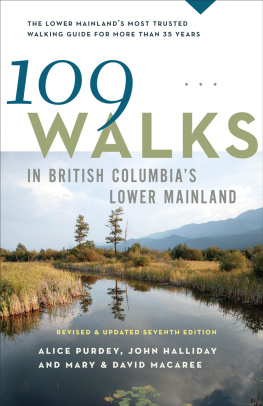

The Fraser Valley stretches in an alluring triangle 150 kilometres from its apex near Hope to the great rivers three-fingered delta at Vancouvers southern edge. On a geological time scale, the valley is all new landsediments 500 metres thick scoured by the river from the British Columbia heartland during tumultuous eons of land erosion, vulcanism and glaciation. The sediment filled what used to be an inlet of the sea, bounded by the Coast Mountain ranges to the north and the Cascade Mountains to the south. In all of B.C.s deeply indented and fragmented coast, the valley is unique, the largest area of fertile arable land in the province. And thanks to a government policy of agricultural land preservation, it is still mostly an idyllic rural landscape, a mosaic of small farms that is divided east-west by the surge of the Fraser River. Though increasingly nibbled at the edges by expanding subdivisions, the valley offers worthwhile country road explorations.

Above the yellow fields of daffodils around Bradner rise the snowy peaks of the Golden Ears, so named because of their golden hue at sunset.

The river was the valleys first transportation route, used by First Nations who lived along its banks and later by European miners boating upriver to the Interior goldfields. Steamboat landings along the way became the focus of later towns and villages. The first land track through the valley was slashed by Hudsons Bay Company fur traders, who followed a First Nation trail from White Rock beaches up the Nicomekl and Salmon rivers to the Fraser, where they later founded Fort Langley. Later trails were made by surveyors mapping Canadas boundary along the 49th parallel and by the Royal Engineers, who carved the first wagon road from New Westminster to Hope and the goldfields beyond. Later still, railway travel dominated the valley: first the Canadian Pacific and the Canadian National and then the feisty little B.C. Electric Interurban, which provided passenger service on its all-electric tramcars until the 1950s. Now the automobile era has taken over, and there are roads everywhere.

The Trans-Canada Highway dominates the valley, but this can be avoided. A great many smaller roads wind through the heart of farm country still embellished with old barns and pioneer houses, dairy pastures, orchards and vineyards, fields of berries and vegetables, farm markets, nature preservesand a gentler, slower pace of life. And when one lifts ones gaze from the fields, there is always the beauty of the mountains. The highway drive from Vancouver to Chilliwack takes less than an hour; on country roads, the same journey could very well take all day, a day spent driving slowly and savouring the serenity.

Our first excursion begins with a visit to Barnston Island, a fat little crescent-shaped island, one of several beached in the lower Fraser. Amazingly, it still can only be reached by an odd little ferry: a barge, accommodating five or six cars, pushed by a tugboat. The service is free and runs on demand from 6 a.m. to almost midnight. (The residents apparently like the access the way it is, having voted down plans for a bridge.) Also amazingly, for land so close to a growing metropolis, the island is mostly farmland protected within the Agricultural Land Reserve: a wide-open country space laced with weedy drainage ditches and sprinkled with a few old barns and farmhouses, an organic beef farm, a herb-and-vegetable farm, two dairies, cranberry fields, cows, goats, sheep, ponies, and many hawks and eagles. Along the south shore, the small Katzie First Nation reserve accommodates homes and small docks for fishboats.

Devitts farm barn is one of the few remaining pioneer structures left on Barnston Island.

Lying low in the river, the island farmland is shielded from floods by a high perimeter dyke. A 10-kilometre loop road on top of the dyke provides paved footing for winter walks, when the mountains across the river are ethereal with snow, and hoarfrost coats the wayside weeds. Spring is lovely, too, with young goats and lambs in the fields and dandelions thrusting up beside every ditch. The island has become a popular biking destination, especially for young families on sunny weekends. Whether you circumnavigate Barnston on foot, by bike or by car, it will be a pleasant excursion. To reach the island, drive east on the Trans-Canada from Vancouver and take 104 Avenue (Exit 50) north to the ferry landing, which is next to Surrey Bend Regional Park. Because of the peculiarities of the ferry, automobile traffic must back on and off the ramp on the island side of the crossing.

Barnston Island was named in 1827 for Hudsons Bay Company clerk George Barnston, who accompanied Factor James McMillan on his journey to found the trading post of Fort Langley, so it is appropriate that the fort is the next destination. Once off the ferry, turn south on 176 Street, join the highway heading east, and then take Exit 58 onto 88 Avenue, which is signposted for Fort Langley. Turn left (north) on Glover Road. The village that grew up around the fort has become almost a destination in itself, for it still holds many traces of its pioneer past, including vintage homes, two heritage churches, a large and shady Victorian graveyard, a magnificent community hall, antique shops, boutiques, restaurants and several museums. One of the museums is located in the 1915 Canadian National train station, which is surrounded by banks of peonies planted by the station masters wife. From the riverside parking lot of historic Jacob Haldi House (now the Bedford House restaurant), there is a fine view of McMillan Island and the steepled 1897 church of the Holy Redeemer, situated on the Kwantlen First Nation reserve. Across the river, the snowy peaks of the Golden Ears really do turn golden in the sunset. Until 2009, a ferry crossing the Fraser here added to the antique ambience of the village but has since been replaced by a toll bridge downstream.

Before the establishment of Fort Victoria, the fort at Fort Langley (at the east end of Mavis Avenue) was the main Hudsons Bay Company coastal depot for furs and diplomatic dispatches, the nucleus for colonial trade, industry and settlement. Barrels of salted salmon and crates of cranberries found a ready market in the gold-mining camps of California. The fort is a historic park, and while only one log building is original, several others have been faithfully reconstructed. Stores, workshops and residences (including the two-storey Big House, where the crown colony of British Columbia was first proclaimed in 1858) are well stocked with authentic artifacts, and the forts stockade and bastions have been partially rebuilt, complete with cannons.

In summer, interpreters in antique garb act as workers pressing stacks of furs, making barrels for salted salmon, manning the forge in the blacksmiths shop, spinning, weaving, serving behind the counter in the trading room and engaging in other pioneer pursuits. For a contemplative overlook, climb into a fort bastion, squint through one of the gun ports at the fields and river below, and imagine the wilderness that once lay all around and the isolation the traders must have felt so far from civilization.

The present fort, which dates from 1839, is not the first to be built here. Twelve years earlier, in response to urgent claims of American sovereignty over all the land known as the Oregon Territory, the Hudsons Bay Company, acting for the British Crown, sent the schooner