To my boys Garth, Henry, and Theodore for being at the heart of every community, table, or life I could ever hope to celebrate. You are my joy.

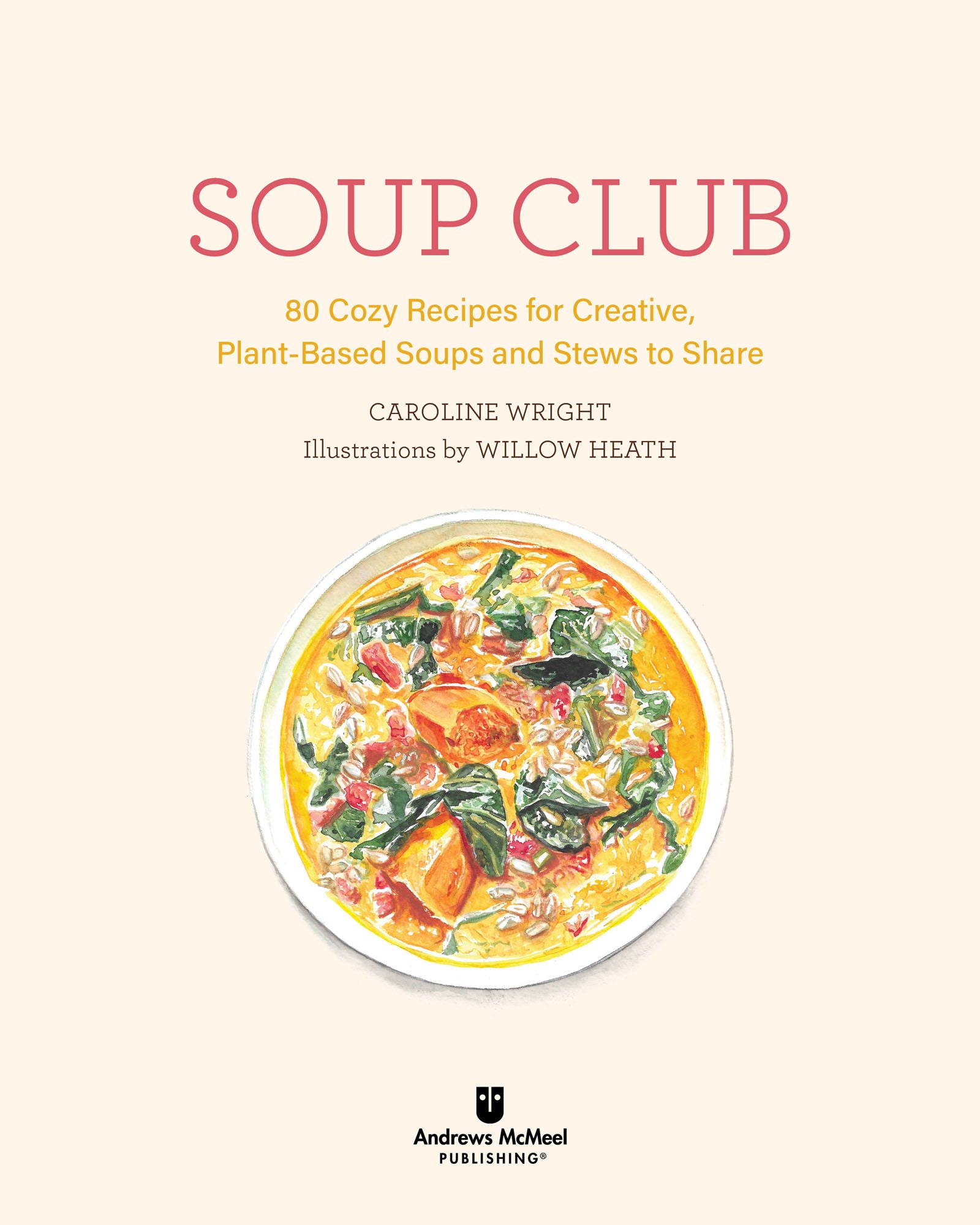

First published by Caroline Wright in 2020. Soup Club text copyright 2021 by Caroline Wright. Haiku 2021 by Amy Baranski. Photographs copyright 2021 by Joshua Huston. Paintings copyright 2021 by Willow Heath. Bean paintings copyright 2021 by Carrie Zabarsky. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of reprints in the context of reviews.

Andrews McMeel Publishing

a division of Andrews McMeel Universal

1130 Walnut Street, Kansas City, Missouri 64106

www.andrewsmcmeel.com

www.soupclubcookbook.com

ISBN: 978-1-5248-7566-4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021936508

Editor: Jean Z. Lucas

Designer: Amy Chinn

Art Director: Diane Marsh

Photographer: Joshua Huston

Production Manager: Carol Coe

Production Editor: Dave Shaw

Ebook Production: Kristen Minter

ATTENTION: SCHOOLS AND BUSINESSES

Andrews McMeel books are available at quantity discounts with bulk purchase for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail the Andrews McMeel Publishing Special Sales Department: .

Contents

The Soup Club Story

At the base of every bowl of soup is a story, often rooted in profound resourcefulness, creativity, and rich personal history. The soups in this book are no exception.

It was mid-February in Seattle when I found out I had a tumor in my brain. After learning that it was cancerous and being told I had a year to live, I noticed the gray and rain differently than I ever had before in the year since moving there; it made me cold, colder still with a shaved head studded with staples clinging to tender wounds. Cooking was out of the questiontoo physicalwhich stole from me my belonging and purpose in my own home. It was as if I had already started to disappear. I spent those days shuffling to the kitchen in my slipp ers, taking note of the intentional movements demonstrated by the occupational therapist I met with after my brain surgery as I moved, to rummage the refrigerator for leftover takeout. Eating soulless food made by strangers behind a counter made me feel empty, I noticed, as I pawed the contents of the containers in my refrigerator for some sign of life with my spoon. The lifeless food I was eating had made me feel lifeless, too.

I was writing a journal online at that point, one where I was documenting my thoughts and feelings for my sons in case my prognosis proved to be accurate; it was frequented by everyone Id ever met and many I hadnt. There I sounded a call for a kind of help that I felt I desperately needed: one for homemade soup. I needed soulful food, meals that would help me and my family heal. One of my dearest and oldest friends managed the flood of responses, a rushing tide of Mason jars with my name on them. Suddenly I was eating soup every day.

Soup began to take on a kind of electricity in my mind, a current that connected me to my community and conveyed their flow of support and sorrow and hope in a digestible way. Other than my keyboard, my simmering saucepan was the only conduit that tethered me to the outside world. Friends and strangers brought me soup, quietly placed in a cooler by our front door. Soup became a kind of currency of support transmitted through this magicians box; into it went soup, from it came hope. Eventually, this soupmostly lentil, the overwhelmingly popular choice in my area of Seattle in which to infuse words that cannot be spokenfilled in the broken parts of my exhausted, worried being. Just like that I was full. And restored, ready to cook.

Every part of my life had shifted since my diagnosis, filled with a kind of meaning that perhaps only those negotiating mortality can fully comprehend. I had an acute clarity and profound appreciation for simplicity. In the process of finding strength, I listened to my bodys call for gentle foods and researched a point of entry for what my health could look like. My decisions were brutal, sudden, and unyieldingovernight I severed lifelong romances with favorite ingredients, meals, and recipes and with them, any hopes Id held for my beloved career as a cookbook author. I no longer ate sugar, chocolate, or gluten, along with what otherwise read like a grocery list of produce, in an effort to calm my system as I sent it into war.

At first, I baked. I quested after these pillars of celebration and comfort as if following a road map to the person I was becoming, required for what I recognized as a joyful life shared with friends and family. It was also a way to translate the meaning of my pastmy beloved baking recipes, the result of my most favorite projectsusing my new vocabulary. It was challenging and rewarding and made me feel like myself.

The Rebirthday

Before I knew it, I had baked my way to a year from my diagnosis, the day I was told I was unlikely to see. In my kitchen was a cake Id figured out along the way that I used to celebrate my rebirthday. Creating the recipe over numerous trials, tweaking the ingredients in a way that suggested, even if only in that single case, a kind of mastery of this unknown palette to result in a celebration of life, community, and family, made me feel whole, powerfulhealthy, even.

Being diagnosed with an impossible cancer at a young age is surreal to say the least. The thing that no one says out loud, however, is that surviving it after emptying out the pockets of your life is surreal, too. Both are hard and strange. You survive to live a life you dont recognize, surrounded by a lot of people who might always see you as sick or less capable somehow. I was confused, scared, and searching for answersthe only thing I knew for sure is that I wasnt done cooking or telling stories.

That is when I started to make soup and bring it to people I love, drop it on friends porches with some chocolate chip cookies during the rainiest months of Seattle winter. I was determined to return the loan of comfort I was given in spades and knew that cooking and connecting with people from an authentic place of love would lead me back to a version of myself that I recognize. Having people other than my family have a visceral reaction to my food restored my confidence as a cook. Nourishing them also nourished me.

There is something magical about soup, I discovered, as I cooked vats of the stuff each week. You assemble these disparate ingredients, and with time and care, they transform into something cohesive and altogether different. As with baked goods, soup makes the person it is served to feel something. The biggest characteristic difference between them, however, is utility and intent: Baked goods are usually celebratory; soup is somewhat its opposite. Soup holds a humble kind of magic. Foremost among its most impressive displays of sleight of hand, it transformed the gray and rain of Seattle winter into, simply, soup weather and me into a survivor.