Contents

Guide

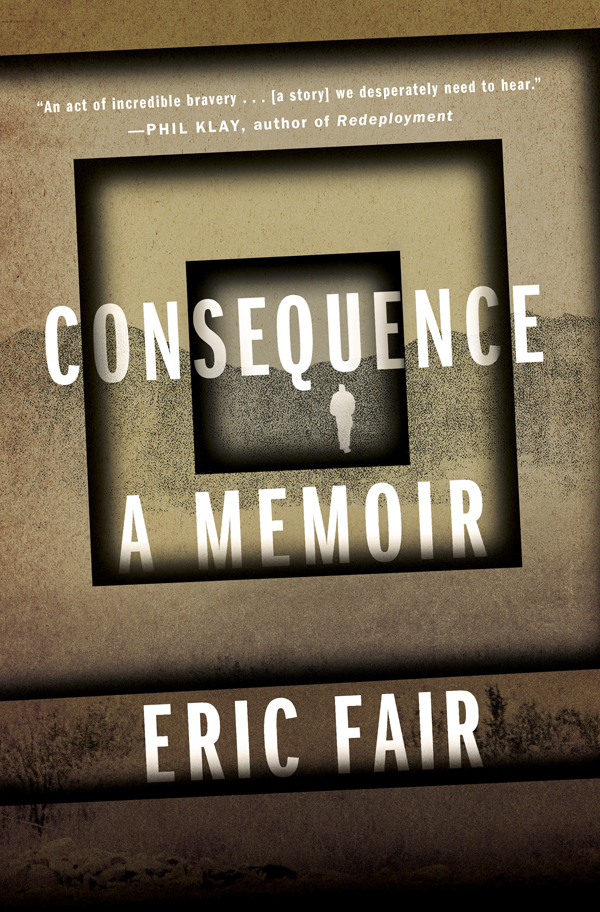

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For my son, Carl Ferdinand Fair

For example, a person is not forgiven until he pays back his fellow man what he owes him and appeases him. He must placate him and approach him again and again until he is forgiven.

Maimonides, the Laws of Repentance

JANUARY 2004

One of the interrogation booths at Abu Ghraib has comfortable chairs. I like to use this booth because theres a small space heater inside that cuts through the chill of the Iraqi winter. Theres even a hot plate to boil water for tea, but it only works when you run an extension cord from the generator, and that prevents you from closing the door all the way. Im interrogating an Iraqi general today, so I make the tea.

Its hard to schedule this booth because everyone wants to use it, and were only supposed to use it when we have someone important to talk to. Its always a good thing if youre interrogating a former Iraqi army officer, especially a major or a colonel. And if you get a former general, like today, then the booth is yours for sure.

The comfortable interrogation booth is designed for an approach called change of scenery. The prisoner is supposed to think hes somewhere else; hes supposed to be tricked into thinking hes just holding a normal conversation in an office building or his living room; hes supposed to forget hes being interrogated at Abu Ghraib prison. But its still just a plywood interrogation booth that smells like fresh-cut lumber, and its still surrounded by the mud and the filth and the incoming mortar rounds that mark Abu Ghraib.

Its early morningthe afternoon sun is still a few hours awayso when two U.S. Army soldiers deliver the general to the booth he is shivering from the cold. I havent had time to read the screening report, so I dont know much about him, but Im sure his story is similar to so many of the others Ive already heard. Hes Shia, which means he probably commanded some poorly trained army unit that probably had more men than rifles. And he probably couldnt pay his men because he embezzled the units payroll in order to fund the bribes that got him promoted to general in the first place. He probably deserted during the invasion, never wanted to fight U.S. troops, and just wanted to go home and live in an Iraq free of Saddam Hussein. This is what all the former generals tell us. None of us believe it.

The report says something about the generals sons being involved in anti-Coalition activities, which doesnt make much sense because hes Shia, and its January 2004 and the Shia havent turned their guns on us yet. But its hard to know whats true inside Abu Ghraib, and its hard to make sense of anything going on in Iraq.

Im working with one of the two good translators today. She grew up in one of Baghdads Christian communities and moved to Michigan during high school, so unlike most translators, shes fluent in both languages. And shes fast. She doesnt wait for you to finish your sentences the way the other translators do, or ask you to repeat yourself, or waste time debating the exact meaning of a word. She talks as you talk, making the conversation seamless.

Im supposed to collect information about the location of the generals sons, but like so many things in Iraq, its an impossible task. Hes been detained since October 2003. Its unclear what, if anything, hes done wrong. Hes had no contact with his family, no information about the outside world, and no cooperation from the men who have imprisoned him. My task is to gain his trust and convince him to betray his sons.

By the time Ive read the initial screening report and gathered basic background information, Ive given up. I shouldnt be here. I should have quit by now. A single month at Abu Ghraib is enough to know that all of this is wrong, but I stay, in hopes of salvaging the experience and finding some way to excuse what Ive done. With each day, the hole gets deeper.

I have the booth scheduled for another hour and I dont have the energy this morning to start on someone new. So I take the time to ask the general about his life and learn what I can about Iraq. I do this with most prisoners, whether they have intelligence value or not. When I write the report, Im supposed to call this the approach phase. Im supposed to be building rapport. Some interrogators talk about how good they are at this, how they develop relationships with prisoners and come to some sort of understanding, opening lines of communication that will eventually produce good intelligence.

Its all bullshit. This is Abu Ghraib prison. The Iraqis hate all of us.

As I talk to the general about the village where he grew up, his service in the Iran-Iraq War, and how much he loves his sons, I ignore the memories from the previous night, when I interrogated a young man in one of the uncomfortable interrogation booths. I made him stand with his arms in the air until he dropped them in exhaustion. He lied to me, said he didnt know anything about the men he was captured with or the bomb that had been buried in the road. So I hurt him. Now Im in a decent room serving decent tea and acting like a decent man. The comfortable interrogation booth is all I need to convince myself that the general and I are enjoying this conversation. Ive fallen for my own stupid trick. When I pour the tea and turn up the heater, I complete the illusion.

As we drink our tea, the translator starts a conversation with the general about what it was like growing up as a Christian in Iraq and how her Muslim neighbors always took good care of her. I was an Arabic linguist in the Army, and while my language skills have faded, I understand enough to allow the translator to steer the conversation for a bit. The general says he was never very religious, but as he gets older he attends Friday prayers more often. The translator seems to like him. I do, too. I pretend the general feels the same way about me.

I talk about growing up in Pennsylvania and attending a Presbyterian church as a boy and how hearing the call to prayer from the mosques of Baghdad reminds me that I should be praying to my god more often. No, no, the general says in English. Not a different god. Same god. Same god. He points at both the translator and me. We are same god.

The general and I are excited to discover that we are both former police officers, so we talk about how hard that job could be and how police officers are the ones everyone turns to when something goes wrong. He says he always thought about going back to police work, but now something is wrong with his kidneys and he has to take too many kinds of medicines.

I take too many kinds of medicines, too. I have heart failure. It cost me my job with the police department. I shouldnt even be in Iraq, but Id been a soldier once, and I felt an obligation to be part of the war, so I lied during the physical and became a contractor. Besides, I say to the general, why do doctors only send healthy men to war?

This makes the general laugh. He hates his doctors, too. He grabs his belly and shakes it and says the medicines make him gain weight. He says I look too healthy to be sick. But he says I should do what my doctors tell me. American doctors are much better than Iraqi doctors. I am too young. I have more life to live.