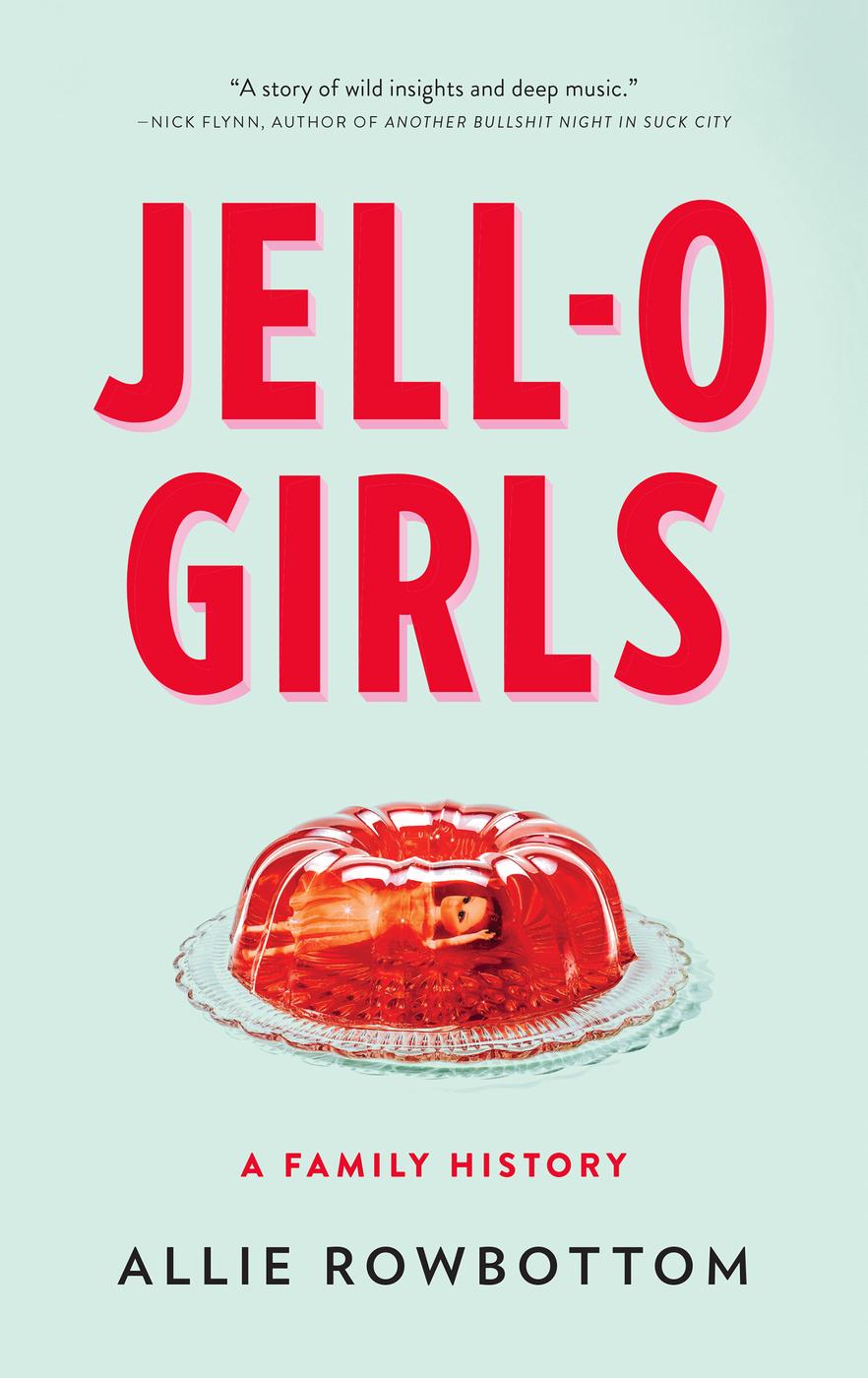

Much of this book is memoir. To write it, I relied on my own present recollections of experiences over time. Elsewhere, I relied on my mothers memory, as recounted to me through the years and as conveyed in her writings. All memories are subjective and affected by time, and I suspect that my mother would be the first to point that out, as well as to offer additions and amendments to the story Ive told here. I am confident, though, that I have been true to her own sense of herself and to her story as I came to know them.

Like many memoirists, I have chosen to change some names and characteristics, compressed or omitted some events, and re-created dialogue.

She leaned forward, mouth opened for the wobbling pink Jell-O I steered toward her. Here comes the Jell-O train, I sing-songed, as if she were a child and I her mother, piloting a spoon into my babys mouth. She kept her lips closed over a laugh, focused on swallowing, and said nothing.

Across the room the TV flashed images of a Main Street somewhere in America, a dilapidated factory. Faded red brick, a smokestack, and a plaque: The Jell-O Company, 19001964. My mother gestured, mouth still full, pointing at the screen, suddenly frantic.

Today were revisiting LeRoy, New York, the newscaster said. Birthplace of Jell-O, where, in late 2011 and early 2012, a group of girls suffered mysterious Tourettes-like symptoms with no known cause.

The camera cut to old footage of the girls, seated around a table, twitching, holding their own hands to stop themselves from flailing. Their eyes were rimmed in black liner. Their hair was neatly swept into headbands. Their lips were glossy and pink. Their mothers sat beside them, tensed against the cameras gaze, as if reined in to compensate for their daughters unbounded bodies.

We had followed the story closely, my mother and I. The mystery of Katie Krautwurst, a senior at LeRoy High School, who, in October 2011, awoke from a nap with her chin frozen. It jutted from her face at an unnatural angle. Her face was in spasm, her whole body twitching. Weeks later, her best friend, Thera, took a nap and woke up similarly altered. She, too, was ticking, throwing her arms, jerking her head, stuttering.

The girls were both popular, both cheerleaders. Both had neatly conformed to the ideal of girlhood in their community, where the football team reigns supreme and Jell-O salads are still served on holidays and at local church potlucks. And the other girls, the girls who followed, also falling asleep, also awakening changed: those girls were cheerleaders, too. But after a while the numbers grew and the symptoms spread. Quiet girls like Lydia Parker were afflicted, too. One girl wasnt a girl at all but a thirty-six-year-old woman, a nurse.

About this mystery illness the media said many things. They said This is how it all started and then offered theories of train wrecks and toxic spills, black mold in the classrooms, witchcraft in the woods. They said There is no end in sight and talked about the diagnosisconversion disorder, mass psychogenic illnessbut always with a disbelieving tone, their faces floating on the television screen, disembodied heads in small side-by-side boxes. On other shows, the girls sat on sofas beside their mothers, answering questions and twitching more violently the more they spoke. I know my daughter, Theras mother said. Shes a normal happy girl. There must be something physically wrong with her. The mothers insisted, and the girls all agreed. A refrain emerged: they wanted the world to know they werent crazy.

Before this, Thera stuttered, arms flailing as she started to speak, I was fine. As she convulsed, the other girls began to as well, their movements picking up until the couch was rocked by the violence of their bodies.

We werent afraid of them, though the nation was. In the years approaching my mothers death, she and I were fixated on these girls. We talked about every unfolding aspect of their story. Hours on the phone about their lives, about our lives, about how our histories were entwined, about how we were implicated. How this mystery illness was a part of a system of symbolism, one older than us, older than Jell-O, consumerism, and America itself. One older even than witchcraft. One as old as men and women and words. This illness and its attendant metaphors, my mother told me, were what shed been trying to write about all these years. This, she said, was why shed started her memoir in the first place.

She pronounced memoir with a soft rmemwahand talked about hers constantly. In fact, the book, almost as old as I was, sometimes seemed to me like my mothers second child, and I resented her flourished memwah for all the years she spent writing it, all the years she spent away from me. But until I got older, I never thought of her book the way she did: as a spell she wrote to stop her family curse and save herself.

Her writing would reclaim her life story, she believed, and the story of her mother before her. Her writing would become a counter-curse.

* * *

We come from Jell-O. It is our birthright, bought by my mothers great-great-uncle by marriage for $450 in 1899 and sold twenty-six years later for $67 million. Jell-O money paid my mothers health insurance. It many times bought my ticket to her bedside in the cancer ward at Mount Sinai, where in the winter of 2015 we watched the girls of LeRoy, searching for glimpses of ourselves.

Even so, my mother rarely ate the stuff. She saw Jell-O as an effigy of a curse she longed to escape. An apron, a kitchen, and long hours spent molding the perfect dessert had always seemed a cage to her, and she dreamed of freedom. Art and travel, music and self-expression, a life sung loudly and lived without fear.

But, sick as she was that winter, Jell-O was all she could keep down. Who would have thought, she whispered one night as I was feeding her. I pretended not to hear. It hurt too much, to acknowledge every incremental loss she bore on the road to losing her life. I learned to be choosy with my empathy. She smacked her lips in mock satisfaction then, and listed the food shed eat if she could. Cold slices of pineapple, fried-egg sandwiches, a burger so rare it dripped bloody juices. Youll get there, I said, coaxing her to take