Copyright 2021 by Nice Lengete

Cover copyright 2021 Hachette Book Group

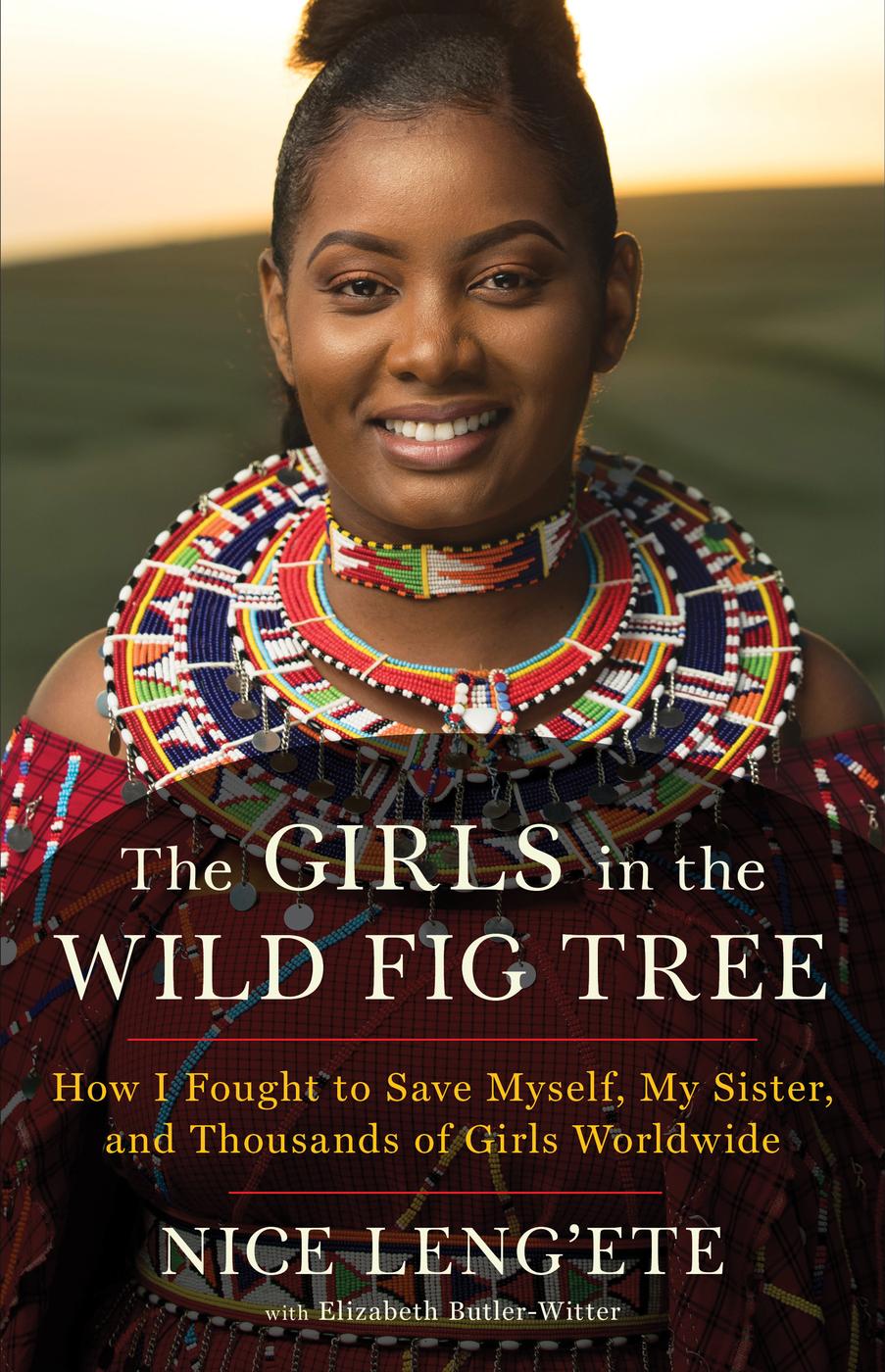

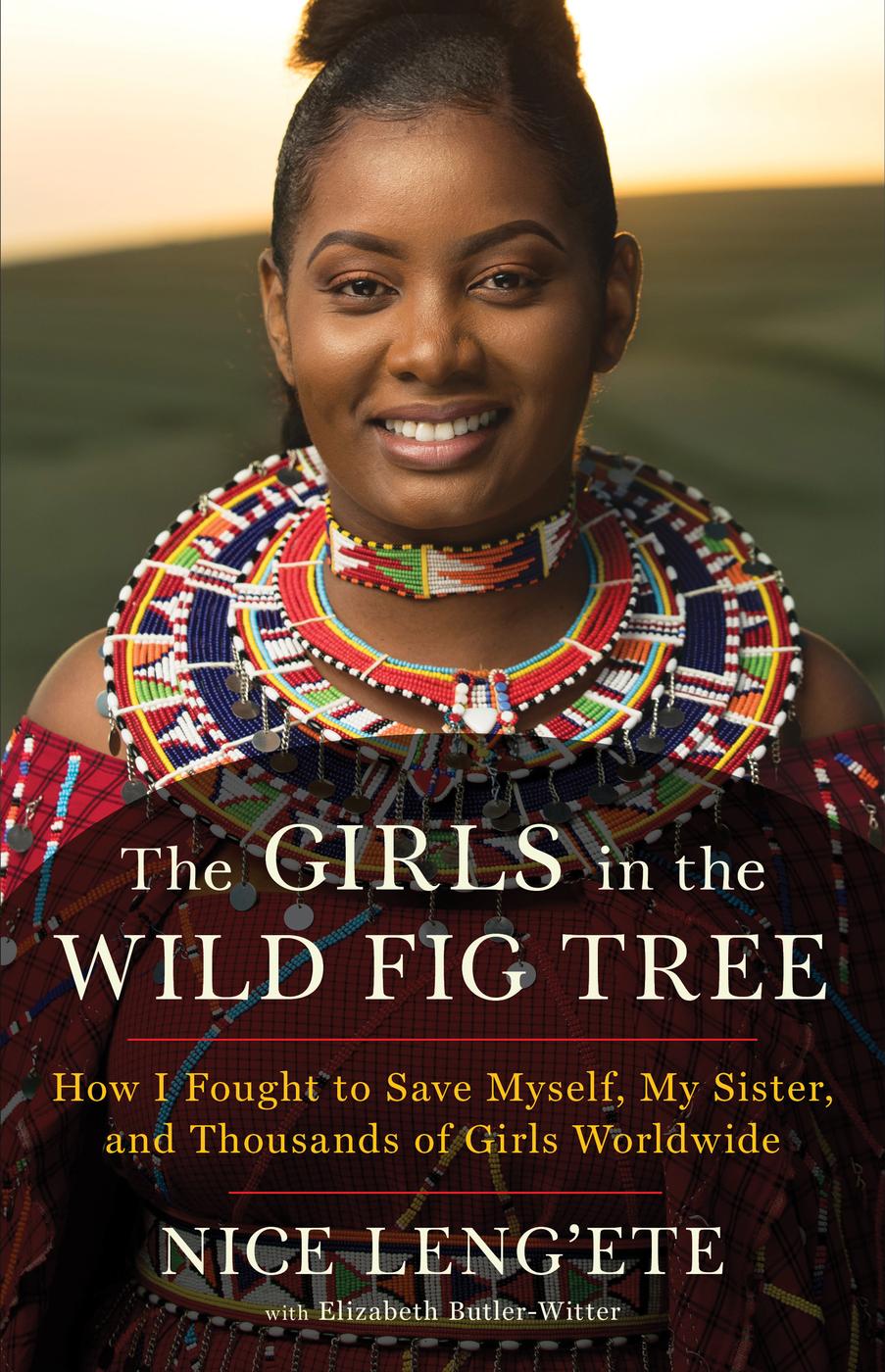

Cover design by Lucy Kim

Cover photograph by Emmanuel Jambo

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany/

First ebook edition: September 2021

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN 978-0-316-26786-1

LCCN 2021930809

E320210726-DA-ORI

To my parents: I hope I have made you proud and that the bravery and strength I saw in you, the joy, compassion, and commitment that you taught me, I have been able to share with others.

To the girls who have been mistreated and forgotten, and who dare to dream: I hope this serves as an inspiration that your dreams and hopes will always be bigger than your reality and that you can achieve anything.

To my sister, beloved family, friends, and all who have walked this journey with me: thank you.

To the girls in A Nice Place Rescue Center and Leadership Academy: you are the future!

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

W hen I was born, people said I had smooth skin and bright eyes. My parents gave me the nickname Karembo, meaning beautiful.

I still like to tease my older sister, Soila, that when she was born, no one called her Karembo. My mother said that when she came out, her skin was wrinkled and her head ended in a sharp point. Even those who looked with the most loving eyes had to admit that she looked a little like a conehead.

We were wanted and loved, coneheads or not. To a Maasai, no man is wealthy unless he has many cattle and many children. As soon as a baby is born, the father hosts a large party. There is tea and roasted meat for everyone, and people bring presents for the family. My father liked to show us off to his friends. He brought a coworker, a white English speaker, to my celebration.

Isnt she a pretty one? he said, watching me smile. Nice baby, nice baby, he cooed.

I like that, said my father. We will call her Nice.

He also named me Retiti, after the oretiti tree that grows in our part of Kenya. It spreads by sending down shoots that form new trunks, and after many years, walking beneath a single tree can feel like walking through a massive grove.

Some people use oretiti bark for medicine. The wood is strong, good for making sticks to help herd animals. The tree produces figs to feed animals and people. It offers shade in a part of Kenya that is often dry and dusty. In the days before most of us converted to Christianity, people would pray under the branches of the tree and make offerings of cow or sheep blood in times of trouble. Some still pray there; the many trunks of the oretiti can feel as cool and sacred as a cathedral.

The oretiti, people say, has many branches. It is a single tree, but it can support many people.

When I was young, the children would tease me for the name. Ret-tet-tet, they would say, like a bird drumming on a hollow log. I hated the name and I picked a new oneNailanteiinstead. It was a traditional girls name with no special meaning; I chose it because it sounded nice.

My aunty Grace says the old name suits me better. Like the oretiti, she says, I have grown to hold many people in my arms. I have sent down roots not just in my hometown but all over the world. People depend on me, Grace says, and if I fell, many people would weep.

It is hard for me to think of myself that wayin my heart, I still feel like a simple village childbut Aunty Grace has a point. I have devoted my life to saving girls from female genital mutilation (FGM), a brutal and sometimes deadly procedure. I have traveled throughout the world, met kings and celebrities, given speeches and received awards. I have helped save thousands of girls. I am still rooted in a small Kenyan town, but I have spread my branches wide.

It is fitting that I was named for a tree because it was a tree that saved my life when I ran away from FGM. Without that tree to hide me, my family would have cut off my clitoris. I might have literally died from FGM, but even if I had survived, I would have experienced a different kind of death. I was a young girl, but after the cut I would have been considered a woman, and I would have been married to an older man. I would have dropped out of school. I would have worked myself to exhaustion every day caring for my husband and children. Instead, because of that tree, my life has branched out into something entirely different. That tree gave me my life, the one I have now, the one that my father could not have dreamed of when he held me in his arms and called me Nice.

I grew up in Noomayianat, a Maasai village near the town of Kimana, close to the border of Kenya and Tanzania. It is an area of plains where elephants, wildebeest, and giraffes graze on grass and the occasional spindly tree. Baboons and vervet monkeys will sneak into human homes to steal sugar or honeylike us, they have sweet tooths. Where water runs, plants are thicker, and animals gather to drink and to hunt one another. Mount Kilimanjaro looms, and at the end of the day, when the sky is clearest, the sunlight glints pink off its icy summit.

My town was small then, though it has since grown much larger. It was just a couple of streets of simple one- and two-story cinder-block buildings. Perhaps five thousand people lived in the town, though many of these, my family included, lived in homes far from the city center. The Maasai own cows, sheep, and goats, so we need plenty of space for our animals to graze.

In the center of town, there was a rickety market, and on Tuesdays people would walk from miles away to display, on upturned crates, their freshly slaughtered goat and lamb, tomatoes and onions from their small gardens, and handmade traditional clothes. Back then, the route from Nairobi was unpaved, so you needed a strong backside to ride the washboarded road. When tourists came, they usually arrived on small airstrips and bypassed our town entirely. The locals got around on motorbikes or their feet. Groups of Maasai women would cross the plains carrying loads of water or firewood. Maasai men, their bright shukas spots of color against fading paint and dusty plants, gathered on corners or under trees.

It is a dry place, and everywhere there is dust. Great funnel-like clouds of it move through the plains. The animals and people walk past, hardly noticing.

The Maasai have lived in this area for centuries. Unlike some of our neighbors, we never hunted. We raised cows and goats and lived off their meat and milk. These are still our favorite foods. We ate very few vegetables or plants. One of my uncles brags that he has never tasted chicken.