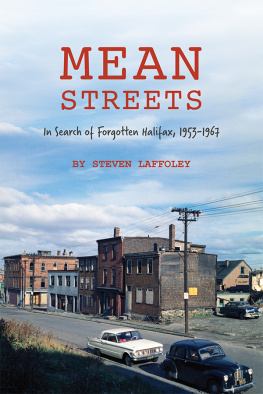

RAZING AFRICVILLE:

A GEOGRAPHY OF RACISM

Razing Africville

A Geography of Racism

JENNIFER J. NELSON

University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2008

Toronto Buffalo London

Printed in Canada

ISBN 978-0-8020-9252-6

Printed on acid-free paper

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Nelson, Jennifer J. (Jennifer Jill), 1972

Razing Africville: a geography or racism / Jennifer J. Nelson.

ISBN 978-0-8020-9252-6

1. Africville (Halifax, N.S.) History. 2. Racism Government policy Nova Scotia Halifax History. 3. Blacks Relocation Nova Scotia Halifax History. 4. Whites Race identity Nova Scotia Halifax. 5. Blacks Race identity Nova Scotia Halifax. 6. Halifax (N.S.) History. I. Title.

FC2346.9.N4N45 2007 971.622504 C2007-903920-0

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council.

University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial support for its publishing activities of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP).

If you dont know my name, then you dont know your own.

James Baldwin

Contents

Acknowledgments

The project on which this book is based has now spanned almost a decade. In this time, I have relied on countless individuals and various modes of support, from the intellectual to the emotional to the very practical none of which can be stressed enough.

My family, friends, and colleagues have all contributed to seeing me through this work and to making it what it is. I especially thank Sherene Razack, who thought she was finished with me after my dissertation, for her ongoing interest and encouragement to publish. I have continued to draw upon her passion and her brilliantly incisive critical gaze while making revisions. The early invaluable contributions from my dissertation committee have also seen their way well into the final work. The thoughtful engagement shown by Ruth Roach Pearson, Kari Dehli, and Nicholas Blomley offered insight and wisdom well beyond the call.

This research was supported by a four-year fellowship from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and I remain very grateful for their support.

While it is standard to thank ones peer referees, I truly cannot say enough about mine. I owe much to the three anonymous reviewers who took the time to engage in such depth with this work. All were respectful and supportive while offering the most constructive criticism. I felt I was in conversation with them as I completed the manuscript.

My editor at University of Toronto Press, Virgil Duff, has been nothing but dedicated and helpful throughout the publication process, patiently and promptly responding to my two thousand new author questions regarding what happens next? (He was also responsible, of course, for finding those excellent peer reviewers.) Mary Newberry worked as both an early consultant and, later, my copy editor. Her footprint is throughout these pages; her attention to detail and her ability to decipher and clarify many threads of argument at once are rare gifts.

I thank Manon Labrecque, another expert on details, for her keen interest, support and bibliographic assistance. I have also relied immeasurably on the friendship and insight of Donna Jeffery, who has always kindly reminded me that this book was worth pursuing and that it would actually, one day, be finished.

My early work on this project benefited greatly from the support and encouragement of Doreen Fumia, Zoe Newman, Donna Jeffery, Sheila Gill and Laura Cleghorn, all of who were instrumental in fostering my ideas, and in sustaining me while I attempted to turn them into something intelligible. On this count, many connections with colleagues at OISE/UT have enriched my learning and continue to challenge me.

I thank Nancy Nelson, Tony Colaiacovo, and Kevin Davison for being dedicated Halifax correspondents during my research, sending much-needed articles and information across the miles. And when I was able to do it firsthand, the staff at the Public Archives of Nova Scotia, the Halifax Regional Library, and the Black Cultural Centre were incredibly helpful, showing interest and patience as I monopolized great volumes of their collections.

Finally, but certainly not least, I thank my husband, Andrew, for what is now nearly a decade of love and support in my work and the rest of life.

I dedicate this book to my parents, Joyce (Tingley) Nelson (193285) and Harry Nelson (193085), and to my grandmother Winnie (Carpenter) Tingley (19092003).

A hundred times every day I remind myself that my inner and outer life are based on the labors of others.

Albert Einstein

RAZING AFRICVILLE:

A GEOGRAPHY OF RACISM

Authoring Africville: A Selected History

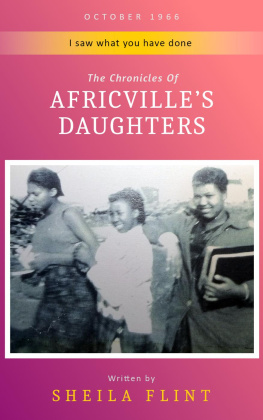

Replying Africville to a question about my work tends to elicit an impassioned response. It is a well-known story at least in eastern Canada and many individuals have their version at hand: It was a shame, a tragedy. The city had no choice. It was a slum. It was the era of integration. What ever happened to those people? We didnt want to leave. Its shocking. It isnt surprising. It was only because we were black. Theyre terribly bitter. They cant forget the past. It will never happen again Other responses betray the ease with which ugly moments in history get erased from public consciousness: Really? Thats hard to believe! When? Afric-what?

To quickly fill in historys blank spaces, I find myself supplying the abbreviated form: Africville was a black community in Halifax, Nova Scotia, on the east coast of Canada, that was bulldozed by the city during the 1960s. I move on to attempt to answer what follows: How? Why? And what would motivate me to write about that? These questions, simple and logical, are the most important ones.

As with any account, opinions vary with individual and group histories, wavering as we draw nearer or farther away. For me, it is a story both immediate and remote. For an academic writer attempting to think critically about race, it is both a crucial moment in the nations history of racism and an ongoing struggle for justice. As a white woman from a working-class, rural town in Nova Scotia, I see Africville as a shadow of the past, mirroring the black community near my own home. Africville is far removed from my experience, yet it is inseparable from the history of white settlement, which shaped its evolution and foreshadowed its destruction.

White perspectives on the many variations of the story are often characterized by a mixture of pity, regret, shame, defensiveness, and anger. A common belief is that Africvilles destruction was an unfortunate incident that was born of a necessary and humanitarian effort. This perspective is accompanied by a sense that the past must be forgotten, that we, and therefore they, must move on. But what is at stake in forgetting the past? Simply put, why should anyone be concerned with Africville today? Some of the answers seem apparent: it is a monumental example of racism at work in Canadian history; it had a devastating effect on the black community; it is a relatively recent event; it is not over in the sense that nothing has really been done about it; it is not unique racialized communities are neglected, denied, destroyed all the time. I think it could, and absolutely would, happen again. It is both shocking and ordinary at the same time. Perhaps the key challenge in writing about it is to hold both aspects in balance: to demonstrate the matter-of-fact banality of racism that belies shock, while conveying the very ugliness and violence of that banality.

Next page