This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our bookspicklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1956 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2016, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

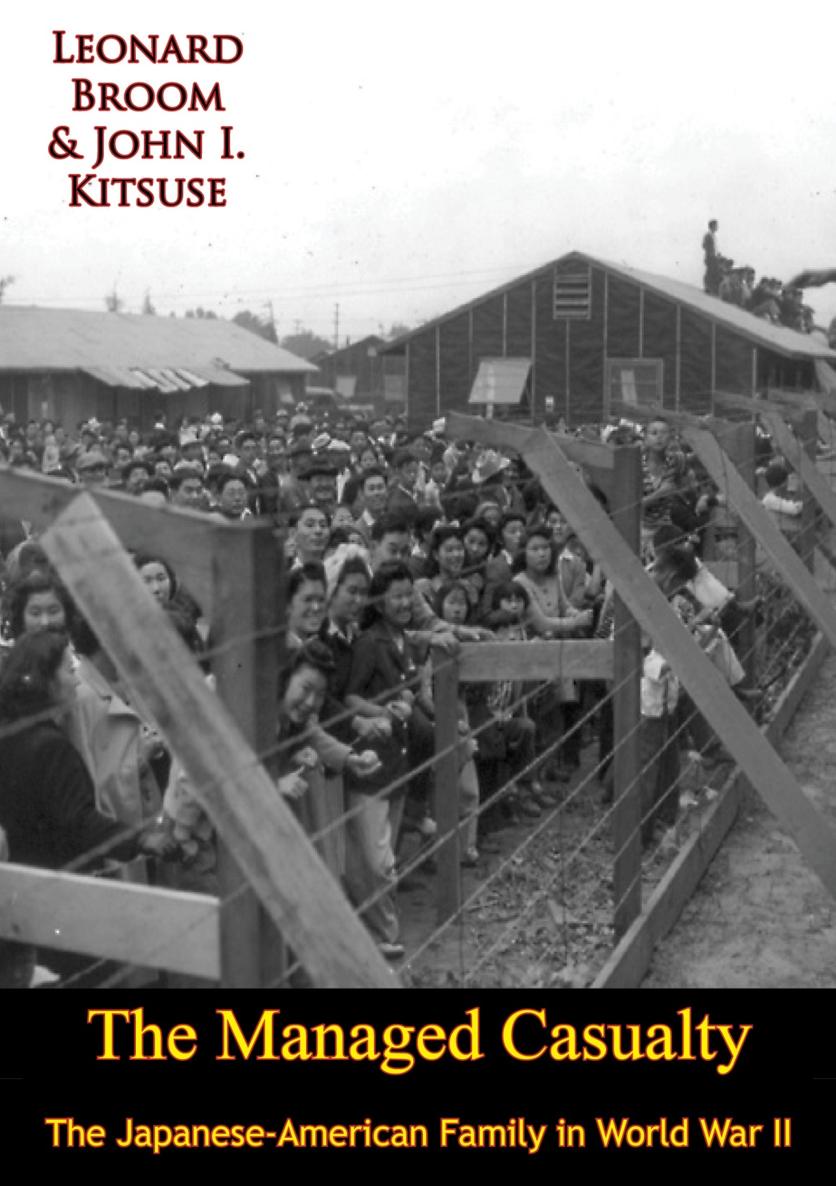

THE MANAGED CASUALTY:

THE JAPANESE-AMERICAN FAMILY IN WORLD WAR II

BY

LEONARD BROOM

AND

JOHN I. KITSUSE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE

T HIS STUDY is an assessment of one major aspect of the adjustment of Japanese Americans to the series of events comprising their removal from the communities of the Pacific Coast early in World War II, their sequestration in temporary centers under governmental control, and their eventual release. It is in a sense an impact study in that attention is directed toward the effects administrative policies had on family groups and the resources these groups commanded to adapt to and ameliorate the conditions imposed upon them.

The preoccupation of the present study is easily justified. The importance of the family, in Japan as well as in the organization of the Japanese communities in the United States, makes this aspect of the social organization of the minority group a major concern for a rounded understanding of the evacuation. The relevance of the family as the unit of study is also indicated by the administrative policy which explicitly directed that family units be maintained in the processing of the population through the evacuation and relocation programs.

Although compilation of cases began at the outbreak of war, the evacuation and relocation of the families and the breaking up of some family units imposed progressive difficulties on the study. Cases would have been easier to complete if the unit of study had been the individual rather than the family, but the institutional focus of the research would then have been damaged. There was, therefore, some unavoidable attrition of cases, and in addition the loss of some cases which might have been saved if the study had not been meagerly staffed and financed.

Confronted by these limitations and opportunities, the study took the following form:

1. An account of the cultural and social origins of the Japanese family system, the immigration experience, the formation of ethnic communities, and the process of family building in the United States.

2. A summary of the conditions obtaining just before the outbreak of the war, giving a base line with which the wartime experience could be compared.

3. A minimal description of those administrative decisions and policies that set the conditions within which the families had to adjust.

4. Against this background the main alternatives available to the families and the adaptations made by them to administrative manipulations are described.

5. The case materials are presented as illustrative instances to give substance and depth to the events being interpreted. It is not claimed that the cases are a random sample of the types of families constituting the Japanese-American population, but strenuous effort has been made to include families that represent the chief categories of religion, occupation, education, urbanization, degree of acculturation, and age and generation composition. {1}

Thanks are due Professor Ruth Riemer for help at all stages of the work, and to Professor E. Ashikaga for verifying the rendering of Japanese terms. Especially, we are grateful to those who collaborated with us in assembling the information for their family histories and for thoughtfully participating in the reinterpretation of their experiences. We have intended to give order to the events contained in the cases, but we have tried so far as possible to avoid the rewriting of reality. That is, we have had both documentary and analytic objectives, and our interpretations are intentionally set apart so that the reader may, if he wishes, use the cases for other lines of analysis.

L.B.

J.I.K.

CHAPTER ISOCIAL AND CULTURAL BACKGROUNDS OF THE JAPANESE POPULATION

T HE PERIOD of Japanese immigration was brief and its termination abrupt. Miyamoto {2} divides the pre-evacuation adjustment of the Japanese population into three intervals: (1) The Frontier Period ending with the Gentlemens Agreement in 1907. During this time the immigrants, nearly without exception, planned to return to Japan. (2) The Settling Period, from 1907 to the Exclusion Act of 1924, saw the formation of Japanese ghettos, economic improvement, the balancing of sex ratios, and the founding of families. (3) The Second Generation Period beginning in 1924 found the people resigned to a life in America and orienting themselves to the rising Nisei {3}

The trends and adjustments were interrupted by the interlude beginning with the evacuation in 1942 and ending with resettlement in 1945. Our study concentrates on the wartime experience of the population. The post-war period, however, has opened a new chapter in which patterns of individual and community adaptation are being set for the next two or three generations.

We shall be concerned here with those aspects of cultural adaptation and family structure which affected the processes of decision-making and adjustment to the exigencies of the evacuation. In general, the most important of these fall into two parts: ( a ) cultural considerations, particularly as expressed in acculturation and cultural conservatism, and ( b ) family authority and dependency patterns, which comprise the critical context in which most decisions were actually made.

This treatment does not deal with traditional community forces, such as voluntary associations and prefectural organizations, which are commonly regarded as important for the Japanese-American population. The nature of the wartime handling of the population consistently undermined community resources, removed or weakened community leaders, and devalued many community institutions. Some 5,000 Issei males, comprising the bulk of qualified leaders, were removed to internment camps at the very outbreak of the war and, although many eventually were returned to their families in the relocation centers, they never recovered their pre-war authority. The peremptory removal of the community leaders weakened the organizations with which they were associated. The members failed to find new leaders and permitted the organizations to fall defunct. Except for the Christian churches, which were the most important agencies mediating between the Japanese and the hakujin population, and the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), an organization of Nisei, the community was left without organizational resources.