Big Band Jazz in Black West Virginia, 19301942

Big Band Jazz in Black West Virginia, 19301942

Christopher Wilkinson

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member

of the Association of American University Presses.

Copyright 2012 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2012

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wilkinson, Christopher, 1946

Big band jazz in black West Virginia, 1930-1942 / Christopher

Wilkinson.

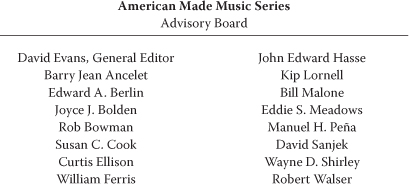

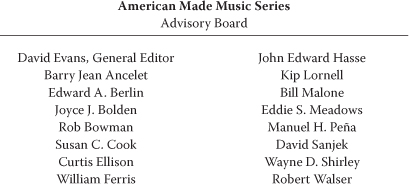

p. cm. (American made music series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61703-168-7 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-61703-169-4

(ebook) 1. JazzWest Virginia19311940History and

criticism. 2. African American coal minersWest Virginia

Social life and customs20th century. I. Title.

ML3508.7.W5W55 2012

781.65089960730754dc23 2011020889

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

To Carroll Wetzel Wilkinson,

Samuel Wilkinson, Bobbi Nesbitt,

Alexis Wilkinson, Jack Wilkinson,

and especially to the memory of my mother,

Jule Porter Wilkinson

Their patience and support made this book possible.

Contents

Preface

Mention the state of West Virginia to many devotees of American music, and they would probably envision small ensembles of white musicians playing fiddles, guitars, banjos, and upright (that is, string) basses. Occasionally, a hammer dulcimer might be part of the sonic mix of such string bands, but no keyboards, rarely drums. Depending on a groups preferred style or that of a particular piece, the music might be labeled old timey or traditional, bluegrass or country. The repertory could range from fiddle tunes of long ancestry and gospel hymns of the early twentieth century to songs by bluegrass masters, who began to define this style after World War II and brought it to prominence by the end of the 1950s, and more recent music by the singer/songwriters who call Nashville, Tennessee, home.

Such perceptions of this musical culture are overly simple. Most obviously, current technology has made an enormous variety of musical styles accessible to West Virginians, who may choose to engage with almost any musical tradition found in the world. Less obvious may be the fact that, despite what may seem at present to be a kind of stylistic and racial homogeneity within the musical culture native to the Mountain State, its musical past was more complicated.

The place of big band jazz in West Virginia during the 1930s and early 1940s has not been studied until now, nor, for that matter, has West Virginias place in the history of big band jazz of that time. These intertwined perspectives reveal a great deal not previously known about how this music was imported to the state from the major northern cities that were home to the leading bands of the period. While one encounters passing descriptions of the tours dance bands made during the Swing Era, until now those tours have not been closely examined from the perspective of the audience to be found along the routes the bands followed. Who were they? In a time of economic crisis, how did they acquire the financial resources to attend dances with great regularity? Where did the dances take place? Who organized them? How did word get out that a band was going to be performing in a particular location?

This study addresses not only these questions but also others more fundamental. How did there come to be so many African Americans living in West Virginia? What brought them to the Mountain State, and why did they stay? How did they become part of the national audience for big band jazz, and how did they stay up to date with its latest developments? What sort of music did they like to hear during a dance, and how did the bands satisfy those preferences? In what ways, if any, does the reception of this music in West Virginia enlarge previous understandings of the connections between a band, its style and repertory, and the audiences it encountered while touring the country?

The answers to these questions (and others as well) emerged as evidence presented itself in the newspaper record and in the scholarly literature on an array of subjects. In addition to the larger history of jazz in the 1930s, equally important are the parallel histories of the coal industry and the labor it required, of state politics and racial policy, and of the formation of a black musical culture in West Virginia prior to the arrival of the big bands. Finally, a number of African American informants, all of whom had resided in the coal fields of the state during the 1930s, provided invaluable insight into life in the states black communities and the place of music in that life.

As evidence accumulated, answers to the questions cited previously began to present themselves. As I will show, during the 1930s West Virginia provided a unique economic and social environment in which African American music could flourish. There were two reasons for this. First, West Virginias coal industry responded positively and proactively to the Roosevelt administrations New Deal legislation that created the National Recovery Administration (NRA), resulting in high levels of comparatively well-paid employment. Second, West Virginia had from the early 1870s forward guaranteed blacks voting rights, and their relatively large numbers assured sufficient influence upon state policies to guarantee a freedom of action not found in adjacent southern states. This included creating their own cultural environment without interference.

The economic conditions created by the policies of the NRA and, after it was ruled unconstitutional, subsequent legislation intended to maintain many of its policies enabled black coal miners in the state to earn wages not only considerably higher than those earned by sharecroppers and other African American agricultural workers in the Deep South, but substantially more than those of blacks working in the heavy industries of the North as well. Thus they had more discretionary income at their disposal than did black folk in surrounding states and further south.

Though the styles of big band jazz and dance music so admired by African American Mountaineers originated principally in the black communities of northern cities (of which the most prominent was New York), black West Virginians were almost as well informed about this music as anyone living in one of those urban areas. This was due in part to the fact that they read the coverage of black music in one of the leading black newspapers of the time, the Pittsburgh Courier, and like most Americans they listened to live performances of this music on the radio. Black West Virginians were knowledgeable about the styles of individual bands, had very strong preferences for one style of dance music or another, and their spectrum of tastes was broad.

I have concluded that, beyond its entertainment value, the principal reason for the popularity of big band jazz and dance music among African American Mountaineers was that it served as a source of racial identity and pride. Unlike the music of many of their white neighbors that was embedded within the folk traditions of the central Appalachians and was thus a marker of

Next page