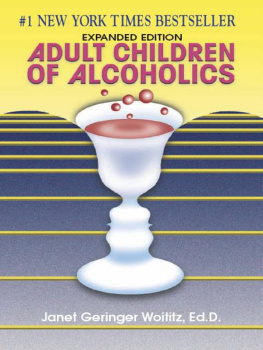

ADULT CHILDREN

OF ALCOHOLICS

(Expanded Edition)

Janet Geringer Woititz, Ed.D.

Health Communications, Inc.

Deerfield Beach, Florida

www.hcibooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

is available through the Library of Congress.

1983 Janet G. Woititz

ISBN-13: 978-1-55874-112-6

ISBN-10: 1-55874-112-7

ISBN-13: 978-0-7573-9341-9 (ePub)

ISBN-10: 0-7573-9341-1(ePub)

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher.

HCI, its logos and marks are trademarks of Health Communications, Inc.

Publisher: Health Communications, Inc.

3201 S.W. 15th Street

Deerfield Beach, FL 33442-8190

Cover redesign by Andrea Perrine Brower

Inside book redesign by Dawn Von Strolley Grove

ePub created by Dawn Von Strolley Grove

CONTENTS

I want to thank those many people who helped to make this book possible. They are the children of alcoholic parents of all ages, and the children of nonalcoholic parents of all ages.

To Diane DuCharme, who convinced me to write this book.

To Sue Nobleman, Debby Parsons, Tom Perrin and Rob, for their tireless devotion to the project.

To Lisa, Danny and Dave.

To Kerry C., Jeff R., Irene G., Eleanor Q., Barbara P., Martha C., Loren S., my students at Montclair State, my students at Rutgers University Summer School for Alcohol Studies, my students in the Advanced Techniques in Family Therapy Course (Westchester Council on Alcoholism), Sharon Stone, Harvey Moscowitz, Linda Rudin, Eileen Patterson, Bernard Zweben and James F. Emmert.

Ten years ago when I began to explore the possibility of writing a book about what happened to children of alcoholics when they grew up, I had no idea what the impact of such a book would be.

It has long been my belief that anyone who sees the world in a slightly different way from others has a responsibility to publish and make those perspectives available to others. It was with this in mind that I began working on the project. My friends and colleagues shrugged their shoulders. I was, once again, making a mountain out of what others considered a mole hillor less. Since it was a familiar position for me to be in, I was not discouraged.

I had done my doctoral dissertation, Self-Esteem in Children of Alcoholics, in the middle 1970s. At that time, the only other work in this area was Margaret Corks The Forgotten Children. There appeared to be very little interest in this topic. The prevailing thinking in the alcoholism field was that if the alcoholic got well, the family would get well. So attention was focused on the alcoholic. After all, most folks find the person with the lampshade on his/ her head more interesting than the partner cowering in the corner. This was not true for me; I have always been more fascinated by the reactors than the actors.

The 70s, when I was doing my research, was an era of great individual exploration. It was a time of encounter groups, drug exploration and sexual freedom. It was a time of III. So the idea that there were millions of people being profoundly impacted by the behaviors and attitudes of others and who had no self to indulge ran contrary to the flow of the time.

I had been outspoken against the Vietnam war when John Kennedy was in office. I had argued for civil rights before the sit-ins. Since I was acutely aware of the overwhelming impact of my husbands alcoholism on me and my children, it was only natural that I call it the way that I saw it. It also was not surprising that my point of view was not shared.

My continuing interest in what happens to the family led to my writing Marriage on the Rocks. I had found that if I gave my clients a talk about what other folks I knew felt about living with alcoholism, it would cut down their denial. When I told them before they told me, they were amazed and relieved. This led me to believe that if someone saw their feelings and experiences in print, it would validate them even more strongly and be helpful in the therapeutic process. Someone needed to bring this reality out of the closet. This information had to be shared.

When Marriage on the Rocks was published, I went on a book promotion tour that covered all the major markets in this country. The idea of the influence of what we now call co-dependency was not of general interest. Although the need was great, the denial was clearly greater.

Ironically enough, almost every radio and television station I visited greeted me with an apology because my book had been stolen. I knew what that meant. Someone living with alcoholism was too embarrassed to ask to borrow the book. I also found that I was invited not because it was a hot topic but because a reporter or producer had the problem and wanted a private session with someone who understood.

The Al-Anon program was and continues to be a primary resource for family members. I will always be grateful for the personal support and professional encouragement I received in those rooms. It was the one place where folks believed that the family could get well regardless of what the alcoholic did. Since the program is designed primarily to serve the newest member living with an active problem, and rightly so, others who are in different life circumstances have to do some translating in order to relate what is being said to their own lives and to gain the benefit. So adult children, although equally needy, dont quite connect. The development of much-needed support groups specifically for ACoAs fills that gap.

In 1979 I was invited to participate in a symposium in Washington, D.C., on services to children of alcoholics. It was sponsored by the National Institute for Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (NIAAA). Twelve of us were invited, and we were told that they only had twenty-four people in the country to choose from. For the first time I felt that I was among other professionals who appreciated the importance of the work.

In 1980, I was invited to design and teach a course on counseling children of alcoholics at Rutgers University Summer School of Alcohol Studies. It was thenand to the best of my knowledge still isthe only course of its type in the world. It is a great credit to Rutgers and the willingness of those involved in the summer school that they were educational leaders. That course set the spark. And it was so wonderful to be validated and supported. Soon there was much interest within the alcohol treatment community, and I received invitations from all over the country to address and train professionals.

At about the same time the adolescents whom I had known through friends in Al-Anon and through my clinical practice were growing up. It was clear to me that the struggles of those who were affected by an alcoholic parent were somewhat different from others of the same age whom I knew and with whom I worked. One day when I was giving a lecture on children of alcoholics, I happened to say, The child of an alcoholic has no age. The same things hold true if you are five or 55. I am convinced that it was from that moment on that people started listening differently. I was no longer talking about the children. I was talking about them.

I made the decision to form a group that focused on the problems of being an ACoA, to work in this area with individual cases and to test my findings nationally. For the next two years I did precisely that. No matter where I went in this country or abroad, the response was the same: You are describing me and my life. At long last I feel validated. I am not crazy. From those findings, I wrote the book Adult Children of Alcoholics.