Acknowledgments

Thank you to all who have contributed their time and knowledge to making this book a fitting tribute to the carriage roads and to the ideals of their creator. They include:

Michele HiltzikArchivist, Rockefeller Archive Center

Keith MillerSuperintendent of Acadia National Park from 1971 to 1978

Ken OlsenPresident, Friends of Acadia

Debbie DyerBar Harbor Historical Society

Brooke ChildryArchivist, National Park Service

Tom ViningNational Park Service

Steven Haynesfor his great stories of the quarrying activities on Mount Desert Island

Bryant Woods, Michael Furnari, and Linda Thayer for their editorial direction.

Willie GranstonThe Great Harbor Maritime Museum, Northeast Harbor

All the people at Down East Books for their confidence and support, especially my editor, Chris Cornell, and designer, Lindy Gifford, who in the end complete the process and make my ideas come to life.

A special thanks to the Historic American Engineering Record (HAER), whose artwork graces this book and the others in my Acadia series. A group of talented artists and historians employed by the National Park Service, the HAER staff members document historically significant engineering works in the United States. Their drawings are not merely impressions of the bridges and buildings but accurate renderings. Each stone is as it occurs in real life. Acadias bridges and buildings were recorded in 19941995, and the team members included: Todd Croteau, Richard Quin, David Haney, harlen d. Groe, Ed Lupyak, Sarah F. Desbiens, J. Shannon Barras, Kate E. Curtis, Joseph Korzenewski, and Neil Maher.

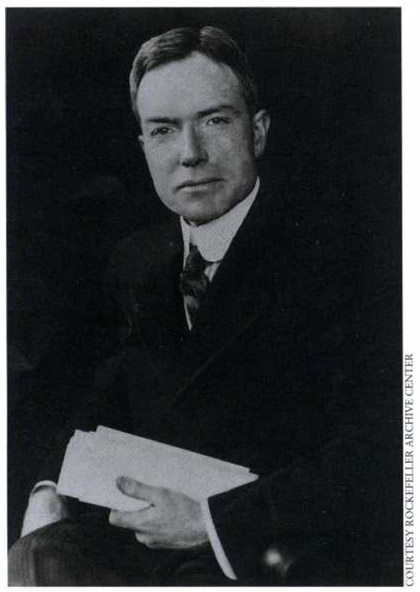

John D. Rockefeller Jr.

John D. Rockefeller Jr. in his forties (circa 1915).

A cadia is unique among national parks in that it was established with the gifts of private donors, rather than by the preservation of public lands. In 1901 Charles Eliot, the president of Harvard College; George Dorr; and other summer residents of Mount Desert Island formed the Hancock County Trustees of Public Reservation. Their mission was to acquire by devise, gift or purchase, and to own, arrange, hold, maintain or improve for public use land in Hancock County, Maine ... In 1903, two small parcels of land were given to the trustees, and in 1908 came its first substantial acquisition: the Bowl and the Beehive, a small pond and mountain near Sand Beach.

That same year, John D. Rockefeller Jr.; his wife, Abbey; and their two children vacationed in Bar Harbor. Abbey was expecting their third child (Nelson), who was born that August. The memories of that summer were so pleasant that the next year the Rockefellers rented again. Eventually, they purchased property in nearby Seal Harbor, where they built a large estate, the Eyrie. This was the beginning of a lifelong relationship with Mount Desert Island and Acadia National Park.

The fifth child and only son of John D. Rockefeller Sr., founder of Standard Oil Company, John Jr. was the heir to one of Americas greatest fortunes and would make the Rockefeller name synonymous with philanthropy. Although the privilege of the familys wealth was obvious to others, it was less a factor in young Johns upbringing than were the strong work ethic of his father and the devout religious attitudes of both his parents. In 1941, John Jr. presented a statement of principles under the title I Believe, which reflect the tenets of his upbringing and the philosophy by which he lived his life. The construction of the carriage-road system and Rockefellers giving it to Acadia National Park, personify this philosophy.

I believe that every right implies a responsibility; every opportunity, an obligation; every possession, a duty.

T hroughout his youth, John Jr. summered at the family estate in Forest Hill, west of Cleveland, Ohio, where his attitudes about life and his love of nature took shape. It was there and at Pocantico Hills, on the Hudson River in New York state, that he also learned how roads and paths could best be designed to heighten the experience of nature.

John Jr. shared a love of horses and carriagedriving with his father and was considered an excellent horseman. Tom Pyle, an employee at Pocantico Hills, wrote, With the four-in-hand he was actually better than either the estate coachman or the head of the stable. Even when the automobile came into vogue, Rockefeller preferred to drive his carriage to work each day and was often seen coaching with his family in New Yorks Central Park.

The pressure of assuming the reins of his fathers empire was a daunting task. John Jr. was an astute businessman, but in 1910, at the age of thirty-six, he decided to change his role in the family company. He would devote his energies to philanthropy, directing his wealth to the betterment of society. The scope of his subsequent endeavors would encompass religion, education, health, and conservation. He showed a special interest in historic preservation and in the formation and development of national parks.

I believe that the rendering of useful service is the common duty of mankind and that only in the purifying fire of sacrifice is the dross of selfishness consumed and the greatness of the human soul set free.

J ohn D. Rockefeller Jr.s love of nature and his abilities as a landscape designer converged in the building of the carriage-road system on Mount Desert Island. He envisioned a network of roads stretching from one side of the island to the other, connecting the major populated areas and opening the interior to the public. He quietly began purchasing land with this mission in mind. Rockefeller was particular about the projects he undertook. He wanted to expend his efforts on fresh, undisturbed areas. Mount Desert Island and the rapidly growing national-park movement provided just such an opportunity. His carriage roads would strike that delicate balance between preserving nature and providing access to those seeking a natural expenence.

The automobile came late to Mount Desert Island. In 1907, the Maine state legislature passed a bill giving individual towns the right to ban or permit cars. By 1913, automobiles were allowed in some towns on the island, but not in the town of Mount Desert (which includes Otter Creek, Northeast and Seal Harbors, Somesville, and Pretty Marsh). This severely restricted vehicular traffic on the island and was a source of concern and controversy among local and seasonal residents. A poem by Herbert Weir Smythe recounts the events of the Mount Desert town meeting where a vote took place on eliminating the prohibition on automobiles.

Now, glory hallelujah, hip, hip and three times three,

Mount Desert town, of fair renown from autos will be free.

In Eden Town they rage around, with horrid smell and soot,

And make Bar Harbors streets unsafe for those who go afoot;

But Northeast and Seal Harbors are in Mount Desert Town,

And the autos in town meeting, have there been voted down.

The poem goes on to explain how one after another, wealthy summer residents, including John D. Rockefeller Jr., rose and pleaded to continue the ban and maintain the quiet charm of island life. They were successful, and the town overwhelmingly voted in favor of the status quo. While this act slowed the wheels of progress, they could not be stopped. Two years later the state legislature, influenced by the auto industry and the other towns on the island, passed a resolution requiring the town of Mount Desert to allow automobiles on its roads. In that same year, Rockefeller began in earnest the task of expanding the carriage-road system that he had started in 1913. His hope was to preserve forever the natural serenity that existed before the automobile.