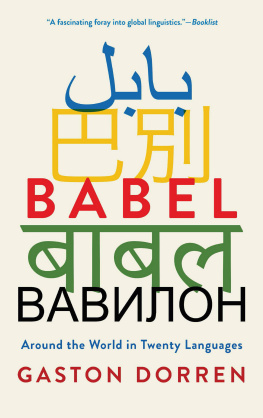

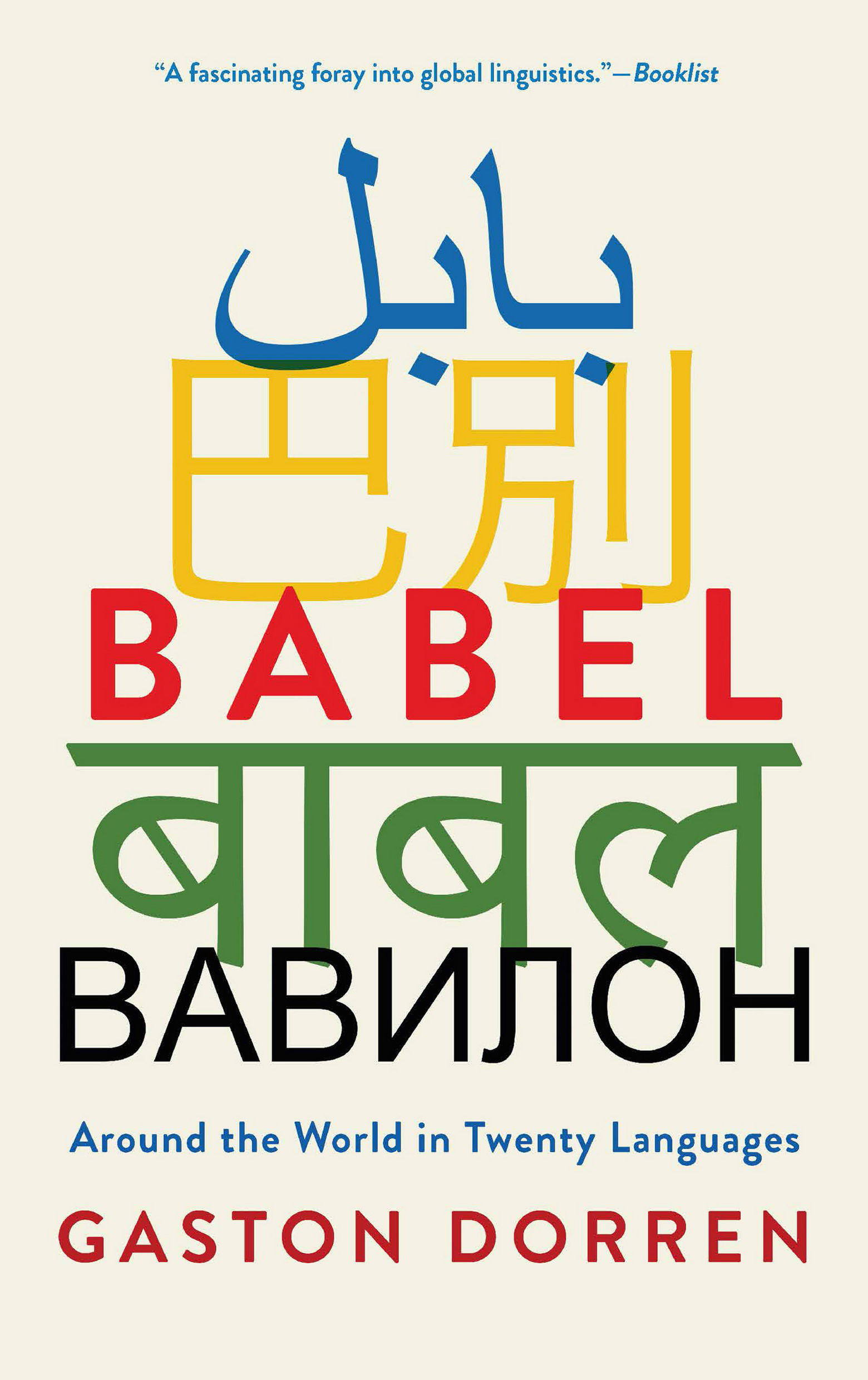

Babel

Around the world in twenty languages

Gaston Dorren

Copyright 2018 by Gaston Dorren

Cover design by Keenan

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or .

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by Profile Books

Published simultaneously in Canada Printed in Canada

First Grove Atlantic hardcover edition: December 2018

ISBN 978-0-8021-2879-9

eISBN 978-0-8021-4672-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title.

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

18 19 20 21 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Language is such an intimate possession, something that one possesses in the same measure that one is possessed by it. Language is bound up with the foundations of ones being, with memories and emotions, with the subtle structures of the worlds in which one lives.

________________________

Alok Rai,Hindi Nationalism

C OUNTING THE WORLDS LANGUAGES is as difficult as counting colours. There are scores of standardised languages, such as English, French, Russian and Thai; making a tally of them is as easy as counting the colours in a Mondrian painting. But most languages have never been standardised. In many areas, there is only a multitude of local varieties, and deciding where one language ends and the next one begins is as hard as distinguishing individual colours in a Turner painting. So there can be no definitive total. That said, 6,000 is a common estimate for the number of languages spoken and signed in todays world an average of one for every 1.25 million people. Such amazing diversity what a Babel we live in!

Or do we? Heres another statistic: with proficiency in just four languages English, Mandarin, Spanish and Hindi-Urdu you could smoothly navigate most of the world, without any need for an interpreter. Hindi-Urdu and Mandarin are widely understood in the two most populous countries on earth, Spanish will serve you well in much of the Americas and English is the nearest thing we have to a global linguistic currency. So much for Babel, one might think.

The worlds biggest languages, which are the subject of this book, are causing the decline of hundreds, even thousands of smaller ones. This is a tragedy, as smaller languages fall out of use across every continent, wiping out valuable knowledge codified in words, stories and names Alok Rais subtle structures of the worlds in which one lives. At the same time, the dominant languages in themselves represent more linguistic, cultural and historical variety than is commonly realised. The contrast makes Babel a bittersweet book: the twenty tongues portrayed herein are delicious and dangerous in equal measure.

Between them, these languages are the mother tongues of no less than half the population of the world. Take second-language speakers into account, and the numbers are much larger still. Again, the figures are debatable, but its safe to claim that at least 75 per cent of people on this planet are able to communicate in one of the Babel Twenty. A less pertinent but more exact figure would be this: over 90 per cent of humankind live in countries where one or more of the twenty are routinely used by central government.

How have these big languages risen to their current station? Individual stories differ, but most have this in common: they are lingua francas languages that bridge the gap between people with different mother tongues.

Two of Babels lingua francas Swahili and Malay first thrived as trade languages. Later on, several governments embraced them as languages of administration, but even today theyre spoken more as second languages useful gap-bridgers than as mother tongues. But the primary creator and carrier of lingua francas has always been imperialism Persian, Portuguese and English all outgrew their cradles in this way. Other Asian languages went through similar episodes: Arabic was spread by the caliphate, Mandarin by successive Chinese dynasties, Turkish by the Ottomans and Vietnamese by the kings and armies of the Vit people. Like Portuguese and English, other European languages also piggybacked on colonial empires. Spanish and French were spread by sea, and Russian overland. Nor has history changed its ways or so the people of South India feel, as they vehemently resist the advancement of Hindi as the all-Indian language.

I have mentioned thirteen languages so far. The remaining seven are German, Japanese, Javanese, Korean and three languages of South Asia: Bengali, Punjabi and Tamil. To categorise these as lingua francas would be a stretch. What they have in common is that they happen to occupy compact but densely populated regions.

If the Babel Twenty have triumphed in different ways, thats only the beginning of their diversity. Unsurprisingly, all languages are different in the words they offer, the grammar they employ and the sounds they travel on. Their writing systems are not just alluringly varied in appearance, but also profoundly dissimilar in their functioning. People have different collective feelings about their languages: we find veneration, pride, protectiveness and sometimes indifference, but also, especially among second-language speakers, resignation and even loathing. Languages are put to different uses: most, but not all, are popular with governments and businesses; some have long and rich literary traditions, others less so; some will be maintained by migrants for several generations, while others are soon given up. All languages display internal diversity, but the patterns differ: usually, there are regional varieties; sometimes, theres one for speech, another for writing; or one for formal conversations, the other for informal chats; or different varieties for speaking to ones social superiors, inferiors or peers, et cetera. In other words, apart from being a unique system of communication, each of the Babel Twenty also has its own language history and its own linguistic culture. They are worlds unto themselves.

In the following twenty chapters (plus one bonus semi-chapter) I will peer into one of these worlds, starting with the smallest of the bunch and working towards the biggest, the worlds linguistic superpower. But while each story will focus on a language, it will also focus on an issue, on one particular feature of that particular language. For instance, what does it actually mean for Russian to be related to English? How do non-alphabetic scripts, such as those of India and China, do the same job as our twenty-six letters? If Belgium and Canada have trouble keeping the linguistic peace, how do multilingual countries such as Indonesia manage? How did tiny but colonial Portugal spawn a major world language and why didnt the Netherlands? Why do Japanese women talk differently from men? And how did this book gain the author two Vietnamese nieces?