Copyright 1990 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

Chichester, West Sussex

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Servos, John W. (John William), 1951

Physical chemistry from Ostwald to Pauling : the making of

a science in America / John W. Servos.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Chemistry, Physical and theoreticalUnited StatesHistory.

I. Title.

QD452.5.U6S47 1990 541.3'0973dc20 89-70256

ISBN 0-691-08566-8

ISBN 0-691-02614-9 (pbk.)

eISBN 978-1-400-84418-0

R0

Preface

EVERY AUTHOR will be familiar with that most common and difficult question, What is your book about? During the several years I have worked on this project, I have experimented with several answers. Perhaps the simplest and most satisfactory is that it is an inquiry into how and why a new scientific discipline took root, grew, and flourished in a particular social setting. The discipline is physical chemistry; the setting is America in the decades around the turn of the century.

But such a bald statement demands some explication. Why study the history of entities as disorderly, ill-defined, and common as scientific disciplines? Why select a science as technically demanding and politically inert as physical chemistry? Why focus on the United States when it is well known that this science had its origins in Europe? And why end the story in the early 1930s, a time when some would say that things were just getting interesting?

Ruthlessly honest answers would demand the acknowledgment of chance. Like many if not most books, this one went through several lives and was shaped by all manner of accidental factors that now can hardly concern a reader. But as any student of science knows, just because the context of discovery differs from the context of justification, it does not follow that justifications are unimportant. With this in mind, let me explain, as best I can, the scope and design of this book.

It is about a discipline, and by that I mean a family-like grouping of individuals sharing intellectual ancestry and united at any given time by an interest in common or overlapping problems, techniques, and institutions. There is much ambiguity in this definition. It says nothing about size, for example, or about the degree to which individuals must be related in order to qualify as members of the same discipline. Yet to be more precise would be to exaggerate the exactness of the phenomenon. Disciplines may enroll a few dozen scientists or thousands. They may be tightly focused on a few questions and techniques, or they may be so diffuse as to challenge the skill of the best textbook writer. Some are happy families, with little controversy over methods and goals. Others are fractured into many research schools, each with a different agenda, each evolving its own traditions of thought and work, and each competing for resources and recognition. A single discipline may be all of these things at various points in its history.

Disciplines are difficult to define, but they are important in the intellectual and social life of scientists and scholars, especially those in academe. We publish in disciplinary journals; we work in departments that reflect present or past disciplinary contours; we take and teach courses bearing titles like history of science and organic chemistry; we identify ourselves at cocktail parties and in biographical directories by discipline; our applications for grants and fellowships are read and evaluated by peers, meaning other members of our discipline. With few exceptions, the more actively engaged we are in the production and transmission of knowledge, the more powerfully disciplines influence our behavior and self-images. We are, of course, more than members of a discipline, but our professional lives revolve around these entities; they help us define our ambitions, successes, and failures.

Despite or perhaps because of this ubiquity, disciplines have not enjoyed a favorable press in recent years. They have been described as purely political entities dedicated to serving the interests of small elites and as repressive institutions that stifle creative impulses and impose artificial limits on the growth of knowledge. For some proponents of interdisciplinary education, the discipline is something to be overcome.

Yet the discipline not only confines, it also liberates. The successful discipline affords its practitioners social and intellectual security, institutional support, and a sense of direction and opportunity. Although a small elite may exert great influence within a discipline, it would be a grave mistake to assume that its motives must be nefarious, its goals self-serving, and its influence retrograde. The discipline is not dysfunctional; it is functional. There is a nearly universal tendency for scholars, even those who set out to break disciplinary molds, to organize themselves into such units.

The reason is not far to seek. Disciplines not only lend structure and meaning to lives, they also bring order and significance to knowledge. To appreciate this, it is necessary only to try to imagine a world that ignores them. Any glimpse of unity that a schooling without specialties might afford could hardly compensate for its barrenness and sterility. Few if any of us could flourish on the boundless sea that is knowledge without categories. With no reason to drop anchor here rather than there, with no coordinates or landmarks to mark and communicate positions, a word like exploration would lose all meaning. Specialization, which is as important to science and scholarship as to pin production, would be impossible. Disciplines may shrink our horizons, but they compensate by giving us means by which we can make our knowledge productive.

Disciplines play important roles in all kinds of intellectual activity, but nowhere are they as important as in the sciences. Essential to the sustained accumulation of facts, the elaboration of ideas, and the transmission of technique, disciplines are at least partly responsible for giving modern science its cumulative and progressive character. As Thomas S. Kuhn has suggested, it would be surprising if some form of progress did not result from the concentration of effort on selected problems. Disciplines are lenses that focus individual effort. Scientific disciplines, with their textbooks, journals, abstracting services, review articles, societies, and powerful sanctions against amateurs, are especially powerful lenses. They are strikingly efficient in identifying soluble problems and in bringing resources to bear on such problems.

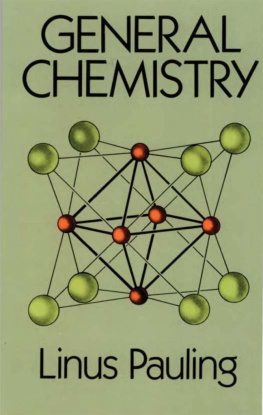

Of all the scientific disciplines one could write about, physical chemistry is perhaps not the first to come to mind. It is not as flamboyant as molecular biology or particle physics. Its practice does not command headlines or prompt Congressional inquiries; its concepts seldom attract popular attention; its story offers comparatively few opportunities to explore issues central to modern political history. Chemists find this discipline difficult to define; physicists sometimes look upon it as a trivial application of their subject; undergraduate chemistry majors tend to see it as the bane of their existencea forbidding hurdle standing between them and a degree. All will grant the usefulness of physical chemistry and the virtues of knowing it, but few develop much affection for it.