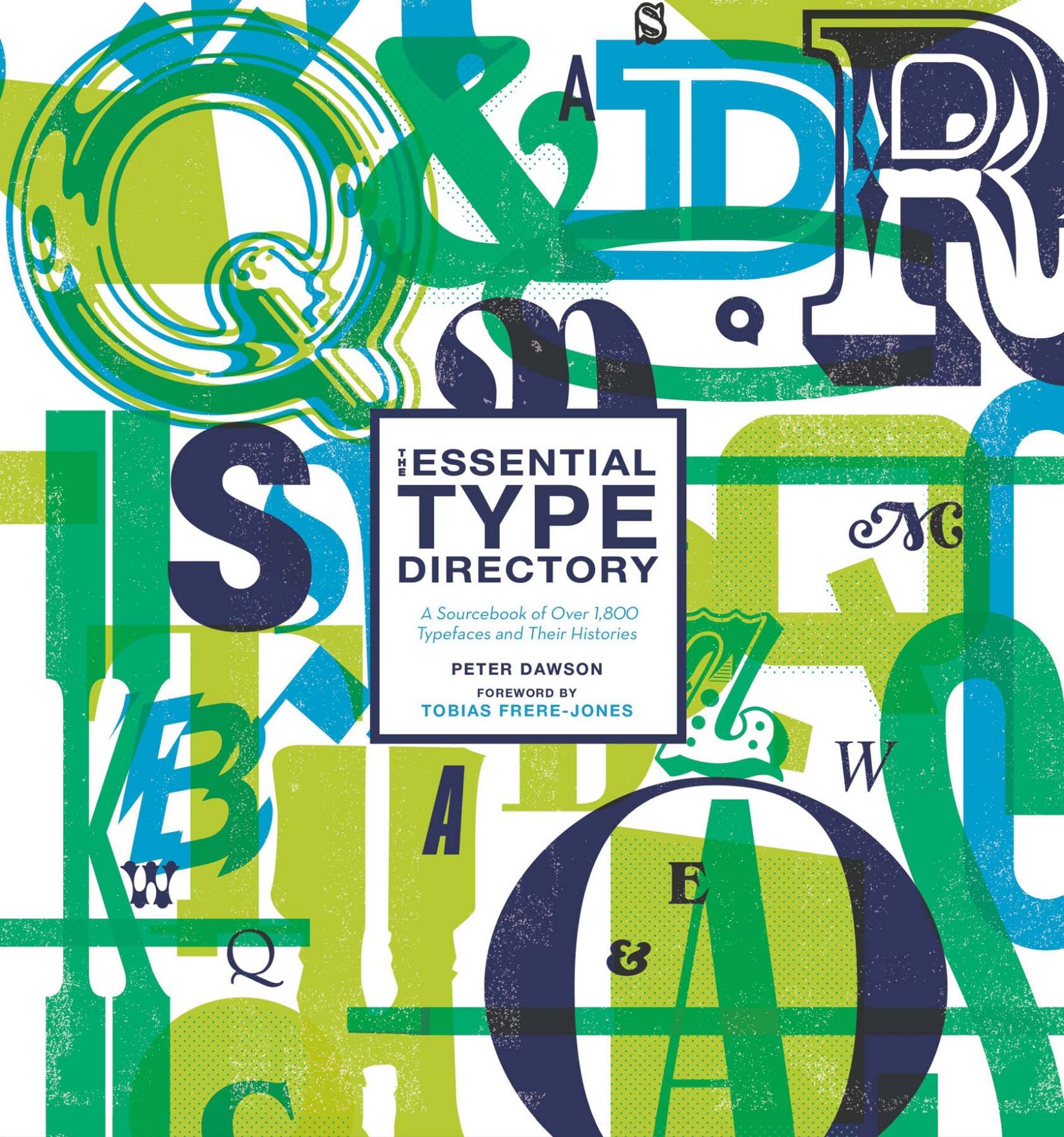

Copyright 2019 by White Lion Publishing

Cover design by Celeste Joyce

Cover copyright 2019 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Book art direction: Peter Dawson

Book design and layout: Peter Dawson, Katie Holmes, Alice Kennedy-Owen, gradedesign.com

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

www.hachettebookgroup.com

www.blackdogandleventhal.com

Simultaneously published in the UK by Thames & Hudson.

First US Edition: December 2019

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers is an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.HachetteSpeakersBureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

LCCN: 2019940029

ISBNs: 978-0-7624-6817-1 (hardcover); 978-0-7624-6851-5 (ebook)

E3-20191120-JV-NF-ORI

Foundry Profiles

Designer Profiles

For Frederick

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

T = top; B = bottom; M = middle, L = left; R = right; BL = bottom left; BR = bottom right; TL = top left, TR = top right.

Page 2. T: Bespoke typeface for Umbro by Commercial Type for the England football team kit; BL: Promotional print for Skate Agora, using Druk by Commercial Type, design by Solo Design Studio, Madrid; BR: Editorial design by Yevgeniy Anfalov using Mineral by BB-Bureau.

Page 3. T: Identity and branding for the London-based Redchurch Brewery, employing Separat by Or-Type, design by Bibliothque; B: Poster series by Design by Atlas for Museu del Disseny using Graphik by Commercial Type.

Page 4. Optical/geometric type system Nine by MuirMcNeil.

Page 5. TL: Albertus as used by Barnbrook studio in the book David Bowie Is; TR: Program promotional design by Emigre; BL: Lost & Foundry typeface collection by Fontsmith; BR: BB-Bureaus ZigZag in use for Antigel Festival 2014, design by Pablo Lavalley.

Page 6. T: Preparatory workings for Dalton Maags Blenny font; BL: Pembroke serif by Jeremy Tankard Typography; BR: Empirica by Frere-Jones Type.

Page 7. TL: FS Benjamin by Fontsmith; TR: The innovative History type system by Typotheque employed in shop window display, design by Pentagram NYC; BL: Berthold Akzidenz Grotesk employed on architects Tim Meins website, design by Sons & Co. / Timothy Kelleher; BR: Chapeau type specimen by Milieu Grotesque.

Page 8. T: Wayfinding and information graphics by Design by Atlas for Museu del Disseny using Graphik by Commercial Type; BL: Detail showing DieseWoche poster employing Univers, designed by Otl Aicher for the 1972 Munich Olympics; BR: Habitar poster by Atelier Pedro Falco using Akkurat Pro.

Foreword

by Tobias Frere-Jones

Looking back on the recent history of type design, its tempting to see a story of technology, liberating makers, and users alike. In the last few decades, the tools for making digital type became available to anyone with a computer and enough patience. Designing a typefacelet alone preparing it for the marketplacewas a lengthy and daunting task. Throughout most of the 20th century, this had been an industrial-scale undertaking (literally). It was thrilling to watch the old ways being usurped and swept away. As it turned out, that was really the smaller part of the story.

The quieter and more profound change has been in education. Those slow, onerous ways of making type were also the venue for training young designers. No school taught these very particular skills, so the young and eager would learn on the job, as they had for centuries. Techniques were closely guarded from competitors, with most designers (punch-cutters for many years) declining to publish any detailed guide to their craft. It was a black art, and deliberately so.

But in the digital age, access to tools begat the demand for skills. And now typeface design is a regular feature of design programs around the world, with a few schools in Europe and the United States even offering degrees or certificates in this very specialized discipline. The spread of type education has brought digital type to its more mature state. And now there are more trained type designers than at any point in history. This discipline has never been so thoroughly populated.

But the question is often posed: why do we need more typefaces? Depending on how you hear it, the question may imply not only a redundancy but an ongoing dilution: the more we make the less it means. But the opposite is true. That diversityeven in fine shadesis a source of strength. If we all used the same type, that choice would become meaningless and wed lose a chance for expression.

We can (and should) discuss the associations the type will accrue through use: the typeface that was used for this ad campaign, this political candidate, that movie poster. But it glosses over an important point: these choices, any choices, have the chance to mean more because other designers used something else. That constant refresh of inventory is the foundation of power. As long as the flavor is distinct and the execution is sound, typefaces will support one another regardless of style. Not in spite of their differences but because of them.

Gathering typefaces from the last centuries as well as the present day, this book hopes to consider that expanding world.

I had my first forays into working with type in my youth, when I spent my later school studies honing my skills to become a commercial illustrator. My ambition was to illustrate graphic novels. Designing posters and graphic ephemera, I used type mainly in the form of hand drawings with a liberal dash of Letraset dry-transfer lettering. At such a tender age, I was not fully aware of the existence of typeface designers or typefaces as a commercial craft and industry.

I was formally introduced to typography and typefaces during my first year of studying for a degree in Graphic Design at Kingston University, Surrey, UK, when my lecturer, the designer Eugenie Dodd, asked me to complete a typographic project. It was a momentous moment as I realized that a whole world of typefaces and their infinite possibilities lay before me. I changed tack in my studies and never looked back. Gone was my ambition of becoming a comic-book illustrator as my attentions turned to becoming a typographic graphic designer.

More than twenty-five years later, I am writing the introduction to Type Directory, having enjoyed a career that has been more like a vocation. I love my role and, more importantly, I am still learning. Over the years, I have used numerous typefaces on a wide variety of projects and have always admired the creative ingenuity, dedication, craftsmanship, and attention to detail of the unsung heroes of the world of type design. These highly skilled members of the creative community past and present number in their thousands. Many are revered as icons in the typographic world thanks to their creative genius and unassuming daily passion. What are invariably their labors of love enable those who work with type to have their creations read in print or online across the world.