Visit our website at www.papress.com.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews.

Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Special thanks to: Madisen Anderson, Janet Behning, Nicola Brower, Abby Bussel, Erin Cain, Tom Cho, Barbara Darko, Benjamin English, Jenny Florence, Jan Cigliano Hartman, Lia Hunt, Mia Johnson, Valerie Kamen, Simone Kaplan-Senchak, Stephanie Leke, Diane Levinson, Jennifer Lippert, Kristy Maier, Sara McKay, Jaime Nelson Noven, Esme Savage, Rob Shaeffer, Sara Sternen, Paul Wagner, Joseph Weston, and Janet Wong of Princeton Architectural Press Kevin C. Lippert, publisher

MY EXPERIENCE IS WHAT I AGREE TO ATTEND TO, William James wrote at the dawn of modern psychology. And yet however perennial this insight may be, it is only a partial truth. Our experience is shaped as much by what we agree to take in as it is by what we refuse what we choose to leave out and both are only partly conscious choices. Our attention filters in a fraction of what goes on around us at any given moment and filters out, thanks to millions of years of evolution, the vast majority of the shimmering simultaneity with which the life of sensation and perception unfolds. This highly subjective, selective, imperfect filtration of reality guarantees that however many parallels two human beings may have between their lives, however much common ground, the paths by which they navigate their respective landscapes of experience will be profoundly divergent.

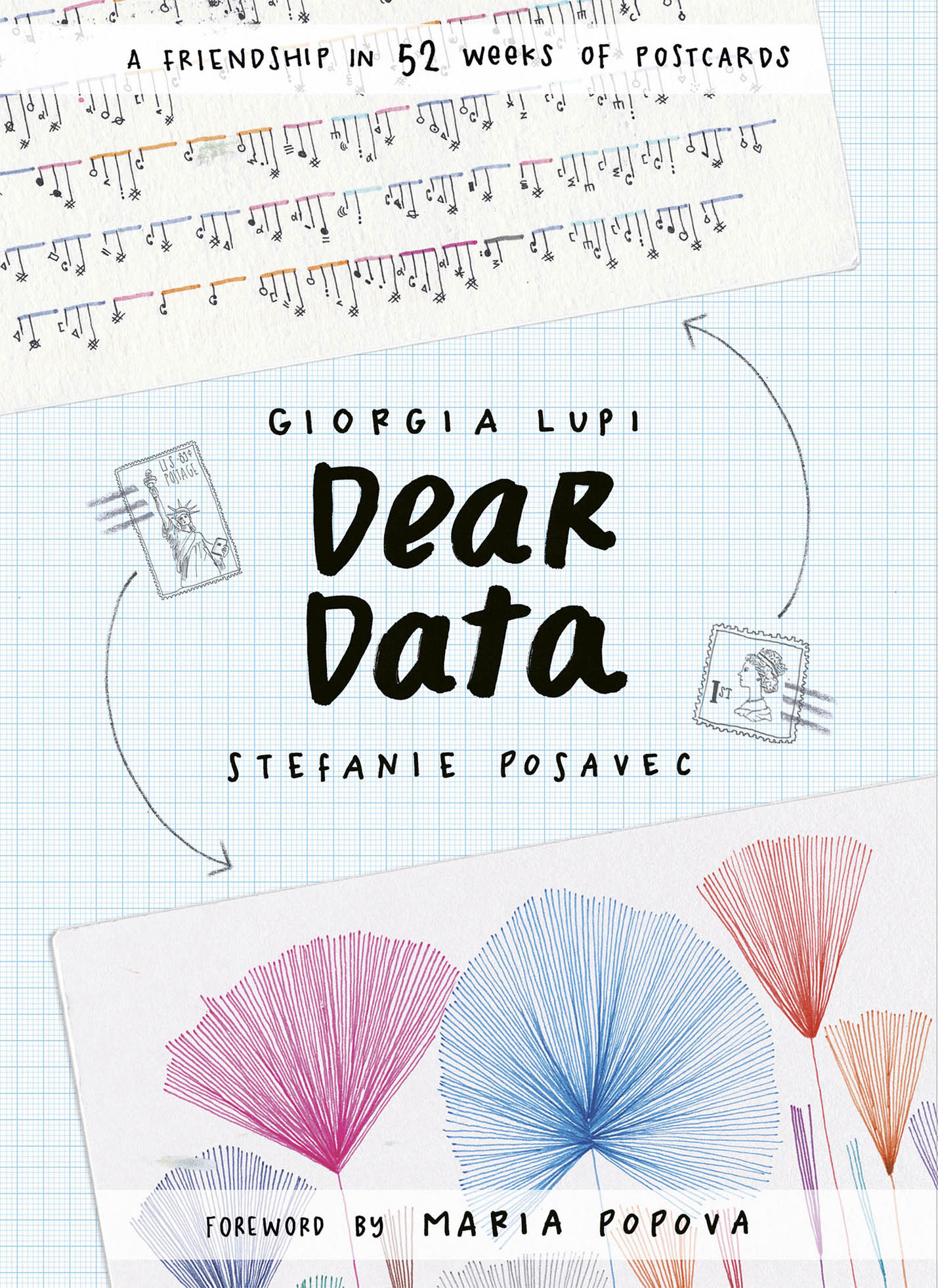

In their year-long visual correspondence project, Giorgia Lupi, an Italian woman living in New York, and Stefanie Posavec, an American woman living in London, capture the inherent poetry of that subjective selectivity. Each week, they jointly selected one aspect of daily life from sleep to spending habits to mirror use and depicted their respective experience of it in a hand-drawn visualization on the back of a postcard, then mailed it to the other. Out of these simple diurnal observations emerges the complexity of the human experience nonlinear, contradictory, and always filtered through the discriminating yet imperfect lens of attention.

The creative constraint of the unifying themes only amplifies the variousness of possibility within each parameter. Despite the substantial similarities between the two women both are information designers known for working by hand, both are only children, both have left their respective homeland to move across the Atlantic in pursuit of creative fulfillment, and they are the exact same age their attentional orientation toward each weeks chosen subject is completely different, both in substance and in style. They deliberately used different visual metaphors and information design techniques for each weeks theme, producing an immensely pleasurable duet of sensibilities side by side, Posavecs signature spatial poetics and Lupis mastery of shape and colour elevate one another to a higher plane of meaning and delight.

A twenty-first-century testament to Virginia Woolfs celebration of letter-writing as the humane art, the project radiates a lovely countercultural charm. Ours is the golden age of Big Data, where human lives are aggregated into massive data sets in the hope that analysis of the aggregate will yield valid insight into the individual an approach no more effective than taking an exquisite poem in English, running it through Google Translate to render into Japanese, and then Google-translating it back into English the result may have the vague contours of the original poems meaning, but none of its subtle magic and vibrant granular beauty.

Lupi and Posavec reclaim that poetic granularity of the individual from the homogenizing aggregate-grip of Big Data. What emerges is a case for the beauty of small data and its deliberate interpretation, analog visualization, and slow transmission a celebration of the infinitesimal, incomplete, imperfect, yet marvelously human details through which we wrest meaning out of the incomprehensible vastness of all possible experience that is life.

MARIA POPOVA is a reader and a writer, and writes about what she reads on Brain Pickings (brainpickings.org), which is included in the Library of Congress archive of culturally valuable materials. She has also written for The New York Times, Wired UK, and The Atlantic, among others, and is an MIT Fellow.

EVER SINCE WE WERE YOUNG, WE HAVE BEEN fascinated with collecting and organizing information from the world around us.

Stefanie remembers going to baseball games with her father, helping him fill out baseball scorecards, slowly compressing inning after inning of the game into pencilled notations on two sides of paper, and feeling excited at being able to capture a moment in time into something that could be neatly tucked away and re-lived at another date.

Giorgia remembers how, as a child, she loved to collect and organize all kind of items into transparent folders that she would then tag with maniacal care. Coloured pieces of papers, little stones, pieces of textiles from her grandmothers tailor-shop, buttons, sales receipts and many more formed her collections, and she remembers the pleasure of categorizing her treasures according to their colours, sizes and dimensions and drawing tiny labels to specify how to read them.

It was only later when we became adults that we realized we were collecting data, and that data was something that we could communicate with while working as information designers.

Unknowingly living almost parallel lives, when we bumped into each other at an arts festival we realized how similar they were. We were each living in a foreign country (Giorgia moved from Italy to New York, and Stefanie, who grew up in Denver, Colorado, now lives in London), we were the same age and were both only children. But, most importantly, we were visual designers who both loved drawing, and specifically drawing with data.

This book is the story of how we, Giorgia and Stefanie, became friends through revealing to each other the details of our daily lives. But we didnt do this by chatting in cafs and bars or on social media. Instead we started an old-fashioned correspondence with an unusual twist. Each week, for a year, we sent each other a postcard describing what had happened to the other during that week. But we didnt write what had happened - we drew it. And we didnt try to draw about everything that had happened to us: we selected a weekly theme.