Acknowledgments

Friends: had I ever known before the richness, the importance of friends in my life? They have become like my nuclear family. They supported me like bookends for months. They made me laugh, they endured my tears, they reminded me that I was me. It was at times a bumpy ride, but they traveled with me every step of the way: Andree Abecassis, Howard Aaron, Joan Clayton, Richard Goldstein, Anthony and Lenore Hatch, Rhoda Herrick, Phyllis Hunt, Cynthia Kayan, Sarah Ravis, Steve Seligman, Myrna Shevin, Mort and Rita Silverstein, Don Sloan, Mort and Barbara Spiegel, Roger Straus, Kathy and Jim Gurfein, and Jerry Traum. To all of you: my thanks.

And to my Mother and Father, for bearing the darts that came from this painful emergence of me, so long delayed. For loving me through it all, for being strong and brave enough to understand, thank you with all my heart.

And to my brother, Ed Loeb, and Melinda, and to David, Jason, Michael, Erin, Andrea, Jessica, Shelby, Laura, Jamie, Matthew, and Alec Loeb: My thanks for your love and understanding.

And to Edy and Abbe, of course.

To Lucianne Goldberg and Mort Janklow, my thanks for their encouragement and help.

To Buz Wyeth of Harper, my gratitude, for his faith in me.

And to my editors: Elisabether Jakab and Burton Beals, who proved that it was possible to do what I wanted to do and then made me do it right, my most sincere thanks.

And those tender people in the hospital, the friends I made there among the patients and staff who touched my life so profoundly: my thanks.

And Jim, my dear Jim, I thank you so very much for your poems, for your love, for being you.

And to Jim Fox and Kevin Fay for more reasons than I can mention here.

Finally, to Peter Dunn, who has helped me through the roughest patches, and helped me to hear the music, long after the dance has ended.

Without Eric Kampmann and Margot Atwell this new edition of my memoir would never have been possible. After reading an out-of-print edition of Dancing, Margot Atwell, Associate Publisher of Beaufort Books, decided that my book had something to say and a story to tell that would matter to readers of a new generation. The gods smiled on Dancings fortunes when Eric Kampmann, President of Beaufort Books, agreed.

To everyone at Beaufort Books, notably Sarah Lucie, who manages to handle a thousand and one things effortlessly while maintaining a sunny smile, my thanks.

Having Margot Atwell and Eric Kampmann enthusiastically bring their own creative passion to every step of Dancings new life has been beyond any writers fondest dream. My heartfelt thanks to Margot for her belief in my work, and to Eric, for making this new incarnation of my memoir possible. I deeply appreciate their support, their creative advice, and the enthusiasm and savvy professionalism they bring to each of their efforts.

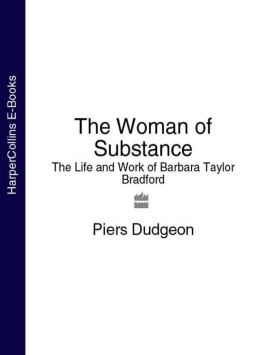

About the Author

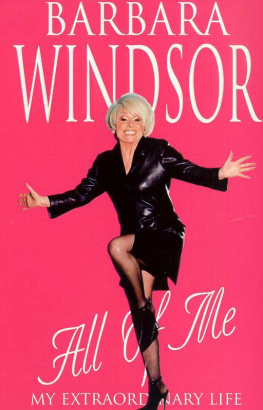

Barbara Gordon has had a long career as a documentary filmmaker at CBS and PBS, and was a writer for NBCs Today Show. She is the winner of three Emmy awards for her work as a documentary film writer and producer.

Her first book, Im Dancing as Fast as I Can, was translated into nine languages, became an international bestseller, and received a nomination as finalist for outstanding autobiography by the American Book Awards.

Long out of print until this current edition, Dancing had sold more than two million copies.

Ms. Gordon is also the author of a novel, Defects of the Heart, and Jennifer Fever, a non-fiction work that explores the social and psychological intricacies, perils, and pleasures in relationships between older men and younger women.

Barbara Gordon was born in Miami, Florida, attended Vassar College, and is a graduate of Barnard College. She currently lives in New York City. She continues to lecture and is presently at work on a book of nonfiction.

Afterword

During the last several years, I have had to rely heavily on various members of the mental health establishment. I have encountered over twenty different therapists, been in two mental hospitals, had countless medications thrown at me, and amassed a staggering number of bills. I have been diagnosed schizophrenic, manic-depressive, cyclothymic personality, borderline psychotic, agitated depressive, hysterical, and just plain neuroticto name a few of the labels this broad brush of scientific endeavor has pasted on me. I have been overmedicated, over-analyzed and underanalyzed. I have been given suicidal advice. But somehow along the way I have met a few wise and tender people. Too few.

All this is to say that psychiatry, because it probes the dark recesses of the human psyche, is a fragile science. And it is terrible to make the discovery, after a series of unfortunate circumstances, that you have also been a victim of the individual and collective ignorance of a profession that, because it is essentially unmonitored, attracts into its ranks a brand of charlatan that wouldnt dare practice in other branches of the medical establishment. A person with no more than everyday neurotic symptoms can handle the greed, the stupidity, the immaturity and the outright mistakesincluding wrong diagnoses and prescriptions for inappropriate medicationsof these inept practitioners. Although he shouldnt have to. But when you are ill, relying on them is like trying to read a book by the light of a firefly.

I managed to survive. But Im not generous enough of spirit to forgive or to forget the brutality of such a system. The road to recovery from mental illness is so interminable, so fraught with its own ups and downs, that fighting incompetence en route is intolerable excess baggage.

And that is at least one reason I have written this book. At first, I had no wish to tell anyone what had happened to me. I have always despaired of people who look for private salvation in the public marketplace. My book began as something to do when I got out of the hospital, something to help me process the overload of data that I had gathered about myself. But then I began to wonder: Was I alone? Was I the only average functioning neurotic who had almost ODd on a tranquilizer? Could I have been that unique, that docile, that nave? I couldnt be.

Still I scorned the idea of going public. It was too private, too painful, too embarrassing. People wouldnt hire me again, love me again, laugh with me again. I knew about the prejudice and suspicion that greet a mental patient wherever he goes. If I kept quiet, that wouldnt happen to me. But it did. And suddenly it was very important to write about what happenedto stop the whispers, the unreturned phone calls, the unanswered letters. I had to clean the air, my air. And if along the way I could unfog someone elses atmosphere, that would be my dividend, my reward.

I had another concern. It was my realization that almost everyone I met in the hospital had been a patient of a psychiatrist outside, and that they all had taken large amounts of mindaltering drugs, generally on the advice and with the consent of their doctors. The number of Americans being given large doses of tranquilizers by their internists, obstetricians, dentistslet alone psychiatristsis staggering. But they arent just medicines. They are drugs that can be anesthetics of the emotions. And their sudden withdrawal can precipitate psychosis and, in some cases, death. Because of my strong feelings about medical mismanagement, because of the prevalence of drug abuseand the softcore prescription-pad variety is drug abuse all the sameI felt I had to tell my story.

I have lived in the cellar of my soul, unable to feel warmth, unable to love, unable to cry, to taste, to smell. I have looked in the mirror and my own reflection shrugged back at me as if to say, I dont know who you are either, Barbara. I think I know who I am now. But have I reached any decisions of cosmic importance? Not really.