www.headofzeus.com

For

Nancy and Jim

Aunt Mary

Phil and Steve

Contents

CHART

MAPS

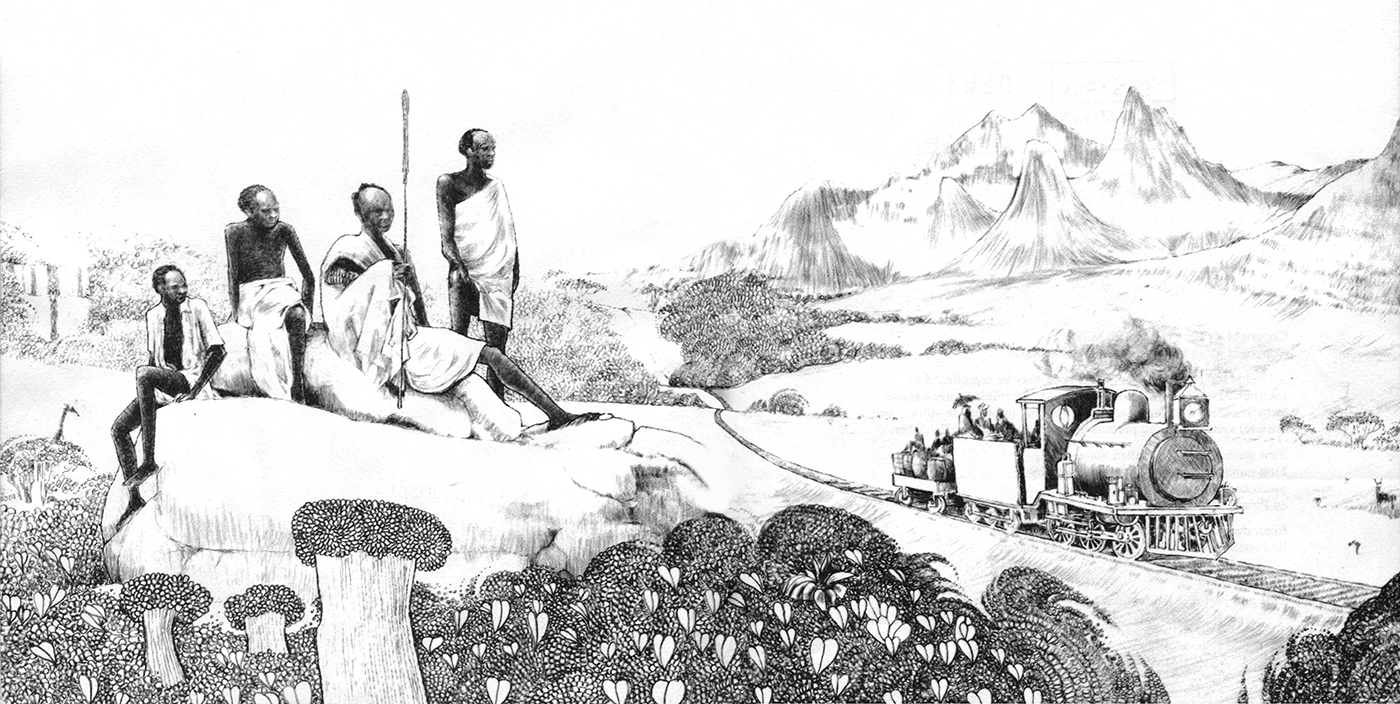

Chapter opening illuminations by John T. McCutcheon from his book In Africa (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1910)

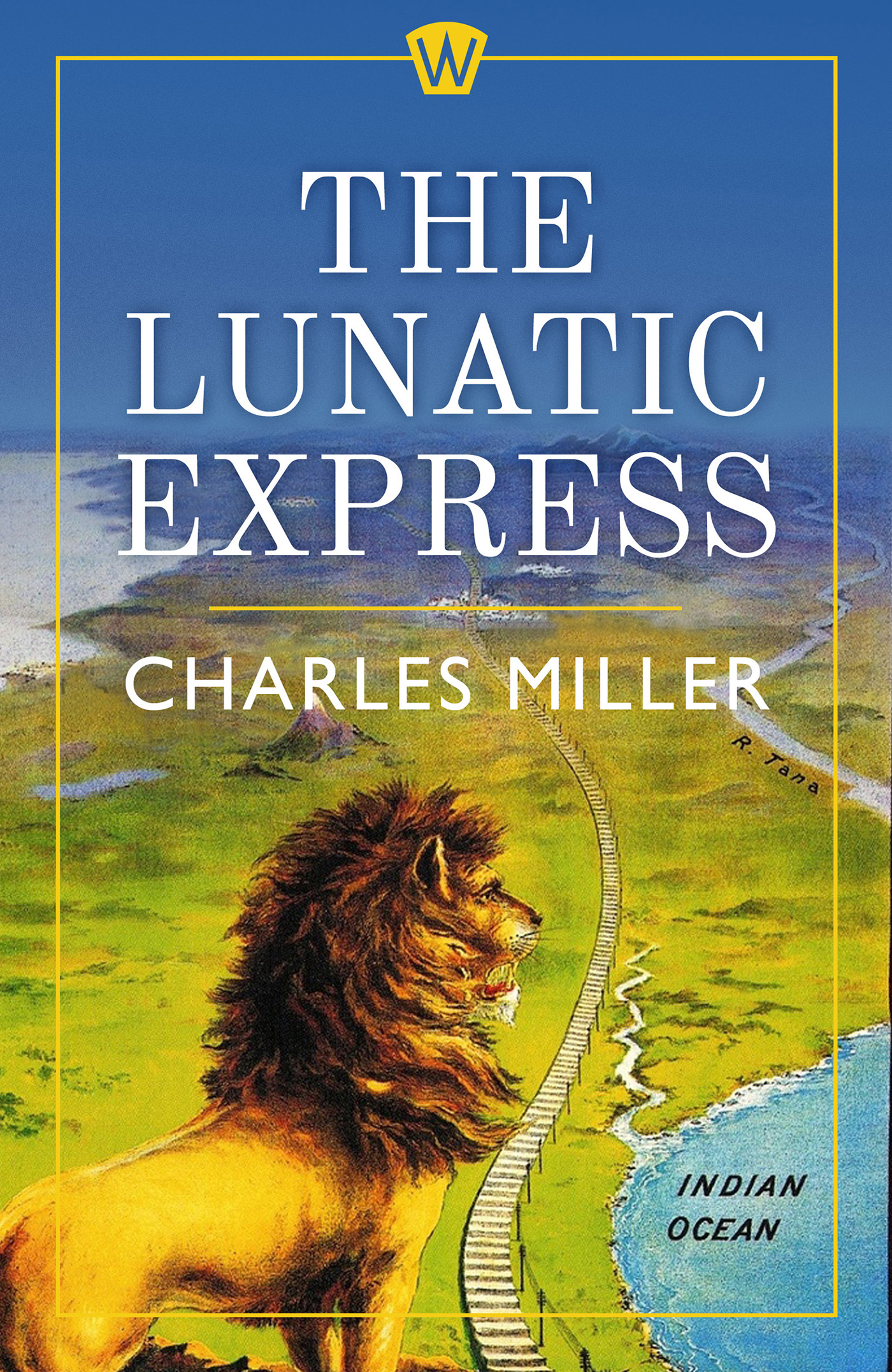

O N D ECEMBER 11, 1895, the British India Steam Navigation Companys two-thousand-ton S.S. Ethiopia crept at three knots beneath the dour battlements of Fort Jesus as she made one of her infrequently scheduled calls at the east African port of Mombasa. On the boat deck stood one of the few debarking passengers, a tall, trimly built man in his mid-thirties who carried himself with the diffident self-assurance of Victorian Englands upper class. His name was George Whitehouse, and he looked about him with interest as the Ethiopia s anchor chain rumbled out from its hawsehole. Shielding his eyes from the sun, Whitehouse took particular notice of the great fleet of Afro-Oriental sailing vessels which were crammed into the claustrophobic Old Harbor, and which now seemed to be huddled about his own ship like a plague of waterborne locusts. For the most part, these craft were huge Arab dhows from the Persian Gulf, but others quickly moved out of the throng and attached themselves, leechlike, to the Ethiopia s hull. They were cargo lighters and flimsy dugouts, manned by Swahili and Bajuni boatmen who wore sarongesque kikois and seemed engaged in a shrieking contest. When one of the dugouts made fast below the passenger gangway, Whitehouse clambered down and stepped awkwardly aboard.

The distance from shore was less than five hundred yards, but the leaking cockleshell had nearly swamped when Whitehouse finally jumped on to a flight of slime-coated concrete steps leading to the wharf at the edge of the town. Here, a small mob of ragged Arabs, Swahilis and Africans immediately began to clout and kick and claw and gouge and bite each other for Whitehouses gear. One man tried to make off with a Gladstone bag but was stopped when someone else kneed him in the groin and vainly demanded ten rupees from Whitehouse for apprehending the thief. Presently the feebler contenders were driven off and Whitehouse followed a bleeding, laughing procession of luggage bearers along the wharf to the foot of Vasco da Gama Street. This narrow alley was Mombasas principal thoroughfare, the only one, in fact, worthy of the name. It climbed a somewhat steep incline which Whitehouse was relieved to discover he did not have to negotiate on foot. The private British company which had administered east Africa before that region officially joined the Empire had laid down a dainty cobwebbing of rails in Mombasa to accommodate a sort of Toonerville pushcart service for the convenience of the citys few whites. Each vehicle, driven by African manpower, was a midget tramcar with a pair of back-to-back seats beneath a canvas awning; one could call it a trolley with a fringe on top. Such a carriage now awaited Whitehouse.

The Vasco da Gama Street branch of the line wound its way upwards between two closely packed rows of buildings: warehouses, Government offices and coral-lime residences occupied mainly by Mombasas wealthier Arab and Indian families. These homes stood two or three storeys high. Their windows were barred and shuttered, and their arched doorsmade of mvule, a rocklike indigenous timberhad ham-sized iron padlocks to guard against breaking and entering. From the upper end of the cramped boulevard rose a diminutive sun-bleached minaret toward which the tramcar clacked laboriously in a formidable traffic jam.

Whitehouse could not decide whether the density of this throng was more arresting than its color. Collisions were barely avoided with lurching Swahilis who wore gaudy kikois or nightshirt-like kanzus and brightly striped vests. The tramcar was continually nudged by white-robed Arabs perched on bobbing Muscat donkeys that were slightly smaller than Great Danes. Sometimes there would be a halt of five minutes or longer, as a string of heavily laden camels, driven by a bean-pole Somali in a brilliantly-hued wraparound cloak, plodded across the tracks ahead. Female garb seemed to glow. Indian saris ran a silken spectrum. The Swahili women were swathed in enormous envelopes of Manchester cotton bearing all manner of gaily printed patterns: caged lions, pineapples, horses, palm trees, monkeys on poles. Even the women who glided by in the grim black buibuis of purdah suggested the carrying out of exotically sinister errands. Tiny gold studs flashed from nostrils, ankles and necks. Bald heads of both sexes, shaved for cleanliness and coolness, reflected the intense glare of the sun. Everyone seemed to be eating a betel-nut sandwich; the nut was encased in a green leaf and the chewers spat big gouts of scarlet juice into the street, itself long stained in that hue. The smell of fresh human excrement rose from open drains to challenge Whitehouses breathing. Beggars with corkscrew limbs and missing faces thrust their dirt-caked bowls from a hundred hidden doorways. The scene was one of torpid vitality, bespeaking Asia more than Africa.

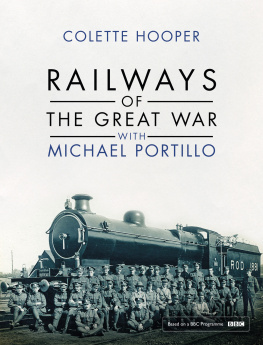

The Mombasa rapid transit line. At left: Police Inspector W. R. Foran.

East African Railways Corporation

Not far from the minaret, Vasco da Gama Street crested the bluff, some sixty feet above the Old Harbor. Whitehouse gave the tramcar driver a handful of pice and made his way to the Customs House where he would pass through the wringer of the bureaucracy which had already taken root in Englands newest colonial possession. Within five minutes he found himself almost awash in perspiration. His white linen trousers, waistcoat and jacket hung from his body like wet dishrags; his cork topee and red flannel spine pad were sodden lumps of blotting paper. This was not caused entirely by the sun; thanks to the Indian Ocean monsoon, the heat in Mombasa, even during December, could seldom be called intolerable. But Victorian Englands greatest contribution to discomfort in the tropics, the corrugated iron house, easily did the work of a Turkish bath. Whitehouse noticed that the Goan customs clerk sat behind a lectern-like desk with a forty-five degree slope which allowed his sweat to cascade freely to the ground without smearing the ink on the quadruplicate entry forms he filled out.

Leaving the Customs House, Whitehouse walked to another corrugated iron kiln a few hundred yards away. Designed to resemble a bungalow, it stood beneath an outsize Union Jack. This was the Mombasa residence of Sir Arthur Hardinge, H. M. Commissioner for the British East Africa Protectorate, who normally made his headquarters on the island of Zanzibar. Whitehouse was made welcome here with the few amenities that the indigent administration of a remote colonial outpost could afford. They were few indeed. Rare was the European in Mombasa who served his guests a steak dinner, all local beef having been butchered from camels which had died in the streets. Vegetables, even when boiled, presented a risk to untrained stomachs. Tea was deprived of its flavor with tinned milk. But one could at least have a good wash; Whitehouse squeezed into a galvanized tin tub, not much larger than a bucket, and sloshed himself down with tepid muddy water. Another luxury awaited him on the veranda: a tray bearing a choice of whisky and Holland beer. Whitehouse decided on the latter. Like all malt drinks shipped from Europe down the Red Sea, this beer had been spiked with a chemical preservative which tended to act like the blow of a closed fist. But it was no less refreshing.