www.headofzeus.com

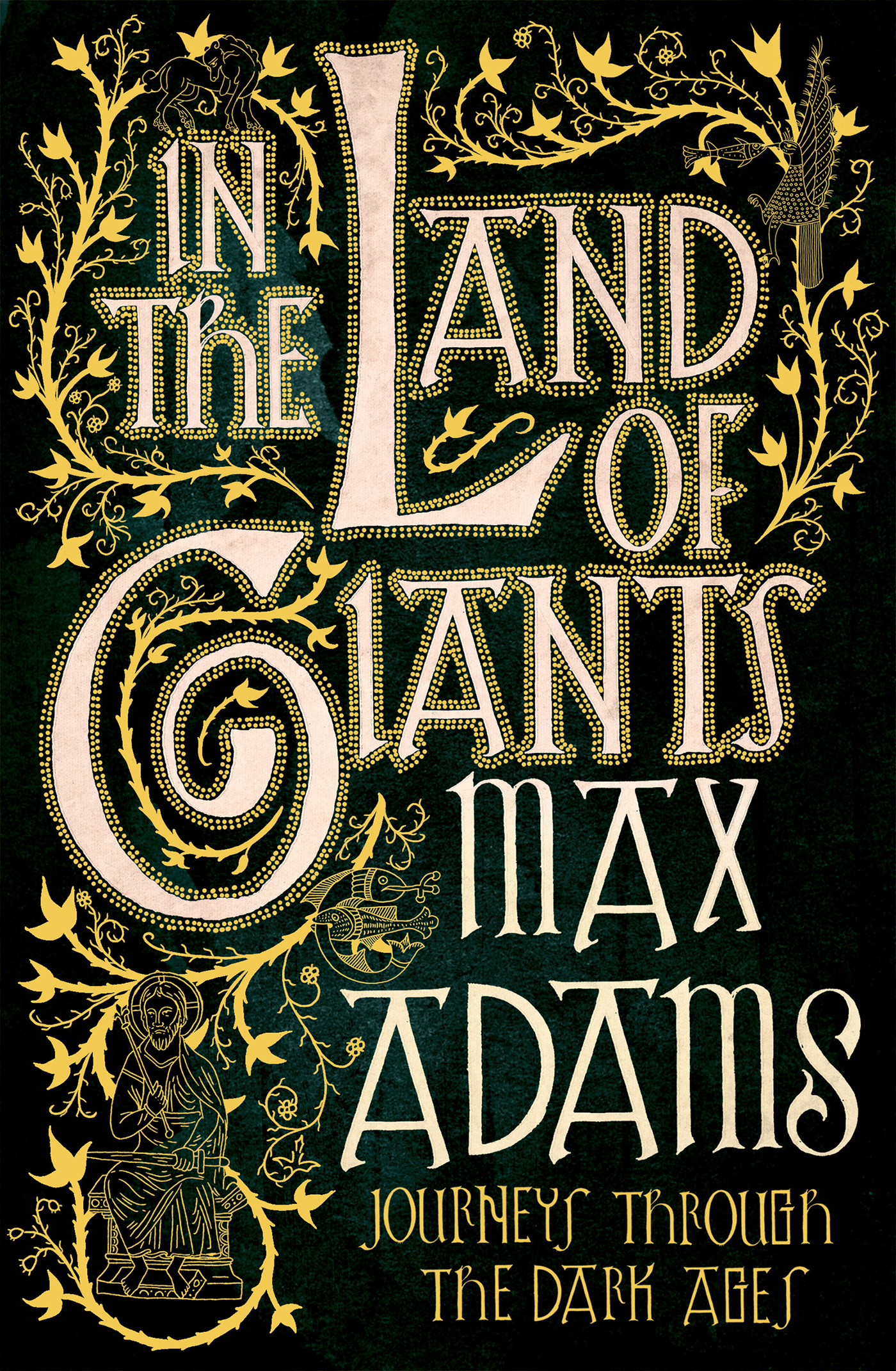

MEIGLE

F OR S ARAH , WITH LOVE

Wondrous is this stone wall, wrecked by fate;

The city buildings crumble, the works of giants decay.

Roofs have caved in, towers collapsed,

Barren gates are broken, hoar frost clings to mortar,

Houses are gaping, tottering and fallen,

Undermined by age.

KILMORY

Contents

A FEW WORDS of explanation are required. The ten journeys took place over seventeen months between October 2013 and March 2015. With two exceptions they appear in chronological order. The sea voyage on Eda Frandsen and the motorbike trip, both for logistical reasons, took place out of kilter. I have put them where I intended they should be and hope that the reader doesnt find the result disconcerting. The interlude walks took place as and when I could fit them in.

At the end of the book is a record of the mileages for each walk: these include accidental diversions and getting lost; all have been measured with a map wheel apart from the sea voyage, for which the data were kindly supplied by James Mackenzie; and the two bike trips, which I measured on the bikes milometer.

All the photographs in the book were taken on the journeys as described. Inline photographs illustrate the text where appropriate; the gallery sections are divided into themes, and readers are invited to make of them what they will. The family of the young boy who accidentally jumped into the frame of a photograph taken at Din Lligwy will, I very much hope, forgive me for including the image in the gallery. He seemed to evoke perfectly the spirit of the place.

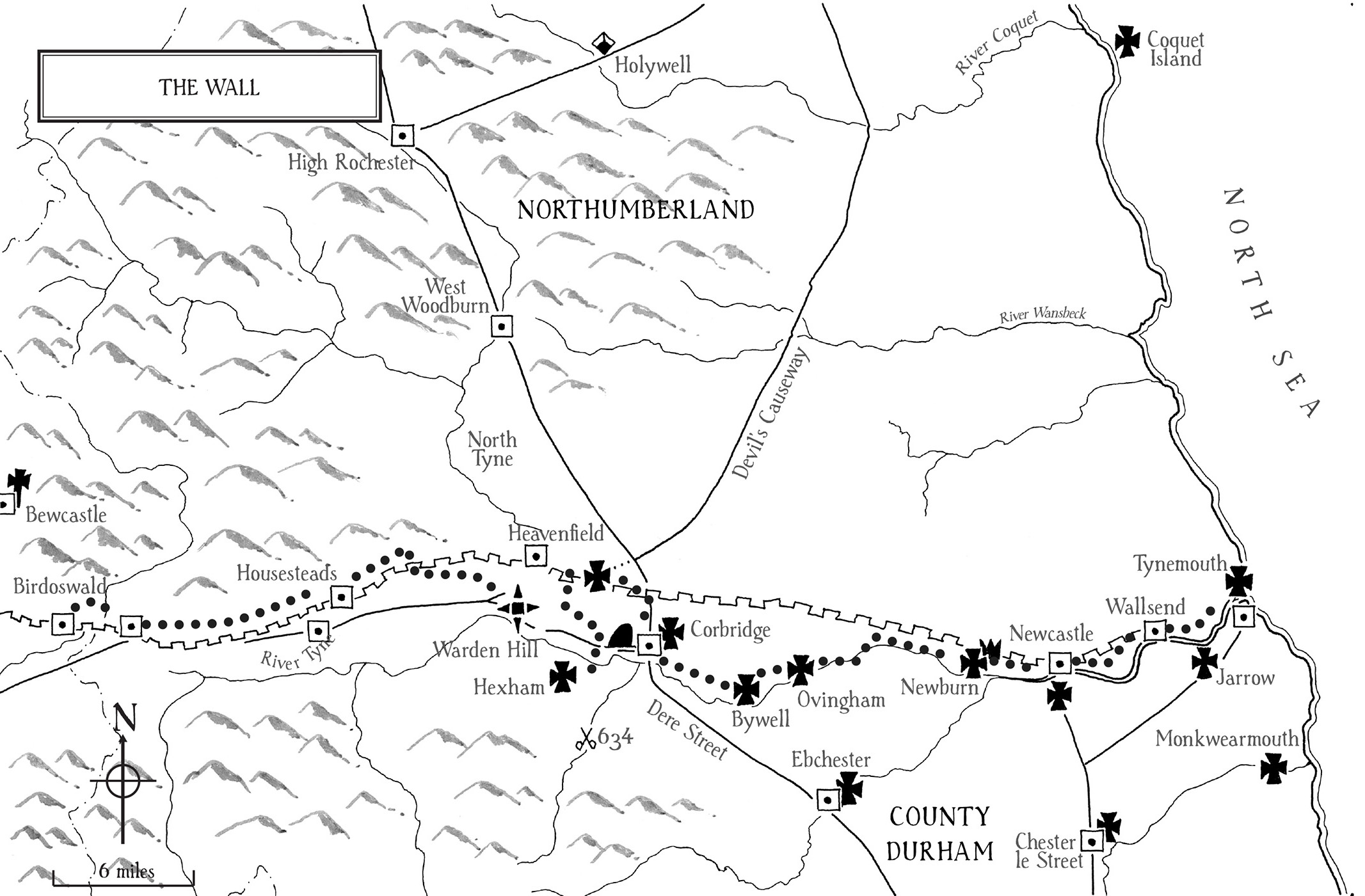

The maps are intended to give an idea of the routes taken and the distances covered each day. I have added some Early Medieval detail where appropriate. With one exception I have used as my base maps the very excellent Readers Digest Atlas of Great Britain , long since out of print but a jewel of cartography and a treasure of information.

At the very end of the book is a short section of recommended reading. Explanations of potentially unfamiliar words have been incorporated into the Notes (pages 43342) as appropriate.

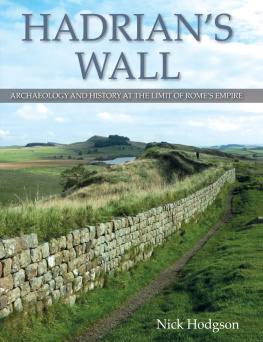

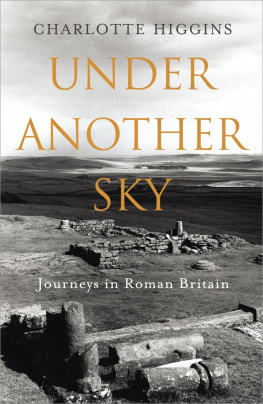

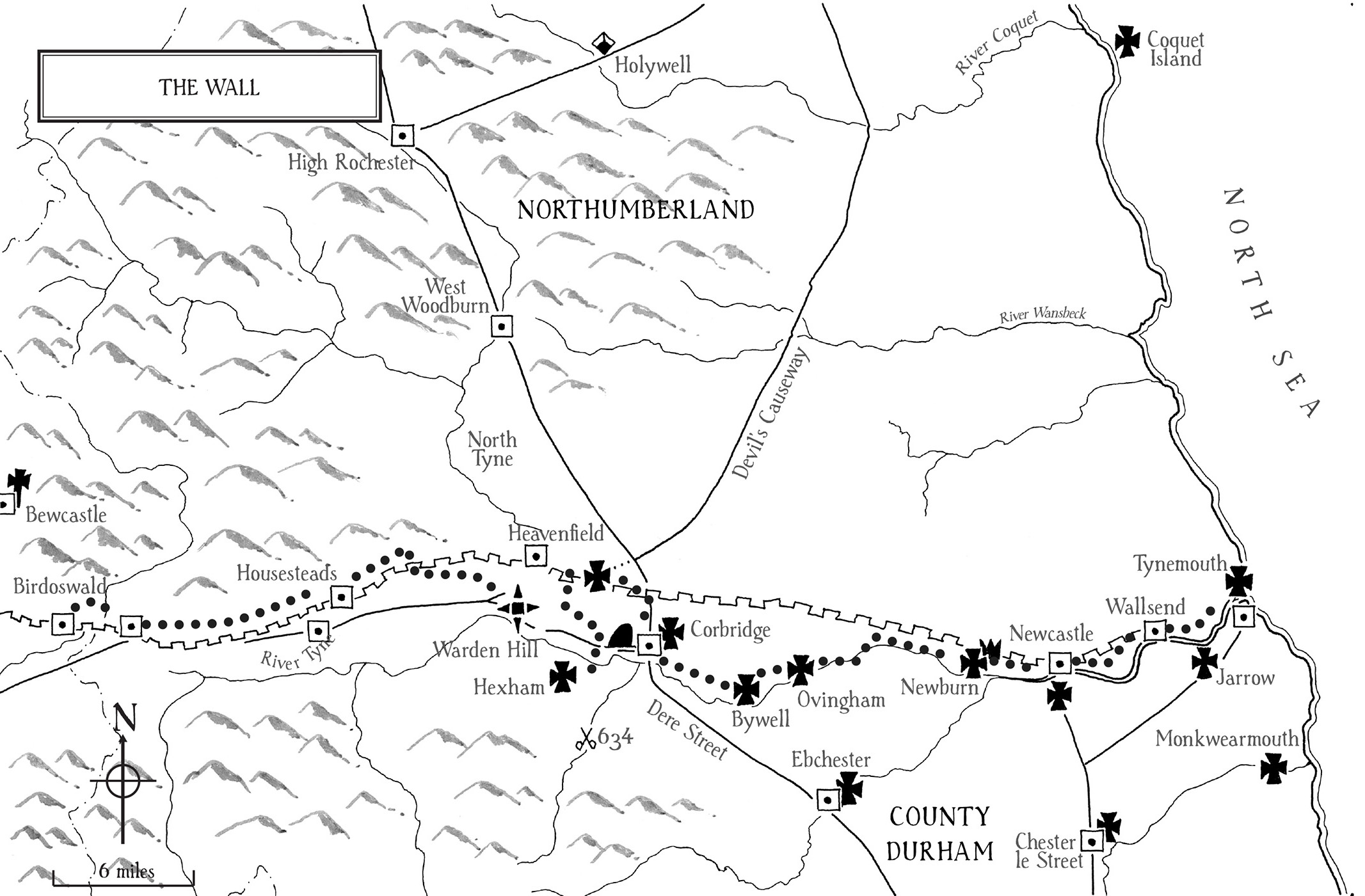

Hadrians Wall Birdoswald fortthe Dark Ages beginlife after the end of the Roman Empirenatives and legionsgranaries and mead halls St Patrick and ArthurGildas and Bede the Ruin a series of journeys

THE WALL

J UST AFTER DAWN on a late November day the North Pennines air is rigid with cold. A thick hoar of frost blankets pasture and hedge, reflecting white-blue light back at an empty sky. The last russet leaves clinging to a copse of beech trees set snug in the fold of a river valley filter lazy, hanging drifts of smoke from a wood fire. The sunlight is a dreamy veil of cream silk.

I am surprised when I come suddenly upon the Wall. I have not followed the neat, fenced, waymarked route from the little village of Gilsland which straddles the high border between Northumberland and Cumbria, but struck directly across country and, with the sun in my eyes, I do not see Hadrians big idea until I am almost in its shadow. Sure, it stops you in your tracks. It is too big to climb over (that being the point), so I walk beside it for a couple of hundred yards. The imperfect regularity of the sandstone blocks is mesmerising, passing before ones eyes like the holes on a reel of celluloid. This film is an epic: eighty Roman miles, a strip cartoon story that tells of military might, squaddy boredom, quirky native gods, barbarian onslaught, farmers, archaeologists, ardent modern walkers and oblivious livestock. I am somewhere between Mile 49 and Mile 50, counting west from Wallsend near the mouth of the River Tyne. The gap in the Wall, when I find it, is made by the entrance to Birdoswald fort. Birdoswald: where the Dark Ages begin.

There is no one here but me on this shining day. The farm that has stood here in various guises for around fifteen hundred years is now a heritage centre. On a winter weekday I have Birdoswald to myself. Just me and the shimmering light and the odd chough cawing away in a skeletal tree. In places the stone walls of this once indomitable military outpost still stand five or six feet high. Visible, in its heyday, from all horizons, the Roman fort layout was built on a well-tested model: from above, it is the shape of a playing card, with the short sides facing north and south. Originally designed so that three of the six gates (two in each long side, one at either end in the centre) protruded beyond the line of the Wall, the fort was not so much part of a defensive frontier, more a launching pad for expeditions, patrols and forays in the lands to the north. Rome did not hide behind its walls; the legions did not cower. Any soldier from any part of the Empire would have known which way to turn on entering the gate; where the barrack rooms would be; where to find the latrines and bread ovens; how to avoid the scrutiny of the garrison commander after a late-night binge or an overnight stay in the house of one of the locals. Uniformity was part of the Roman project.

Any native on any frontier would get to know the layout too. The British warrior might, in those first years of the Walls existence during the 120s, try to attack it; when that failed he would herd his livestock through its gates to his summer pastures and pay a tax on his sheep or cattle. British women would barter their homespun goods for ironwares or posh crockery; one day their sons might be recruited into its garrison. The Brittunculi or Little Britons, as a Vindolanda tablet suggests they were called by their imperial betters, might grow to like the idea of the Empire.

Outside Birdoswald fort, to the east, the frosted surface of a smooth, grassy field conceals the magnetic traces from geophysical mapping of a small village, or vicus , which grew up alongside. These vici were native British settlements, clinging like limpets to their military protectors, supplying them with goods and services and probably with children, wanted or unwanted. Much the same thing happens in frontier provinces today. You see it on documentaries filmed in the dodgier parts of Afghanistanonly there the Taliban regards such integration or fraternisation as a capital crime. When the Western troops leave, and they are leaving as I write, one fears for the safety of the inhabitants. When Rome came to this frontier, she came to stay.

To the south, the line of the Wall, and this fort, are protected by the deep, sinuous gorge of the River Irthing, the western of two rivers which between them create the TyneSolway gap linking east and west coasts. This gap has been a lowland route through the Pennines for many thousands of years. Two generations before Hadrian the Romans built a road along this line, known in later times as the Stanegate, so that they could rapidly deploy troops along its length. Much of that road is still in use, or at least passable. And long after Hadrian, General Wade had his redcoats build a road following much the same route and for much the same reasonin his case to keep Jacobites at bay. The gap between the headwaters of the Rivers Irthing and South Tyne is narrow: no more than four miles. Near Greenhead, just to the south-east of Gilsland, is the watershed boundary, the pass, a choke-point through which modern road and railway, ancient Wall and eighteenth-century military road must squeeze.