Key Points

Skin embryology: the embryology of the both epidermis and dermis is described.

Epidermal development: the development of the epidermis beginning the third week of fetal life and its regulation is treated.

Skin structure: the structure and the ultrastructure of adult skin are detailed.

Introduction

Skin Structure

The integumentary system is formed by skin and several skin appendages (glands, hair, nails, and teeth) [).

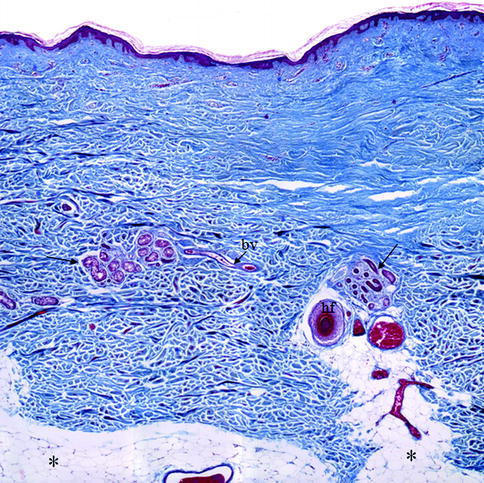

Fig. 1.1

Histological section of human skin. The human skin is composed by a superficial upper layer, the epidermis covering a deeper layer, the dermis. Inside the dermis, numerous glands ( arrows ), blood vessels ( bv ), and hair follicles ( hf ) are evident. Below the dermis is visible the subcutaneous fat ( stars ). Mallory trichromic stain. Original magnification 2.5

The two skin layers are interconnected with each other through epidermal-dermal junctions. These are undulating in section and formed by ridges of the epidermis, known as rete ridges, that project into the dermis. The junction provides mechanical support for the epidermis and acts as a partial barrier against exchange of cells and large molecules. Below the dermis, there is a fatty layer, the panniculus adiposus, usually designated as subcutaneous. This is separated from the rest of the body by a vestigial layer of striated muscle, the panniculus carnosus [].

There are two main kinds of human skin. Glabrous skin (non-hairy skin), covering the palms and soles, is grooved on its surface by continuously alternating ridges and sulci. It is characterized by a thick epidermis divided into several layers, including a compact stratum corneum; by the presence of encapsulated sense organs within the dermis; and by a lack of hair follicles and sebaceous glands. On the contrary, hair-bearing skin has both hair follicles and sebaceous glands but lacks encapsulated sense organs [].

The integumentary system has not only principally protection functions but also thermoregulation, respiration, and perception functions [].

Embryology of the Skin

The skin develops by the juxtaposition of two embryological elements: the prospective epidermis, which originates from a surface area of the early gastrula, and the prospective mesoderm, which is brought into contact with the inner surface of the epidermis during gastrulation [].

The epidermis originates almost completely from the covering ectoderm, and only few cells (melanocytes and Langerhans cells) migrate from other areas. On the contrary, the dermis develops from two different mesenchymal areas; the larger part arises from somatopleure (lateral mesoderm) and the smaller part arises from somites (paraxial mesoderm) [].

Development of the Epidermis

After gastrulation, the embryo surface emerges as a single layer of neuroectoderm, which will ultimately specify the nervous system and the skin epithelium [].

Fig. 1.2

The epidermis formation. Wnt signaling blocks FGF activity on the neuroectoderm that can express BMP proteins so developing the epidermis

Fig. 1.3

Development of the epidermis. ( a ) The covering ectoderm is formed by a single layer of cuboidal, undifferentiated cells; ( b ) the epidermis is composed by a second superficial layer called periderm; ( c ) the germinal basal layer originates a third middle layer, the intermediate layer, whose cells are characterized by the presence of microvillus projections at the surface of the periderm; ( d ) during the fifth month, the intermediate layer proliferates, forming one or more other layers. The periderm cells form numerous blebs and get away in the amniotic fluid (See more details in the text)

Between 8 and 11 weeks, the germinal layer actively proliferates and originates a third middle layer, the intermediate layer (Fig. ].

In the same time, like basal keratinocytes, intermediate cells undergo proliferation and/or differentiation. The loss of their proliferative capacity is associated with the maturation of intermediate cells into spinous cells [].

In the epidermis of the hand and foot, among granular and cornified layers, a thin additional layer, called bright (glossy) layer (stratum lucidum) for its refraction property, lies. This layer is formed by cells containing the fluid eleidin that replaces the granules. All the epidermis layers are formed by cells called keratinocytes because they contain keratin by 14 weeks [].

Epidermal cells must undergo growth arrest before they can initiate a differentiation program [].

The plane of union between epidermis and dermis is smooth until early in the fourth month when epidermal thickenings grow down into the dermis of the palm and sole. About 2 months later, corresponding elevations first appear on the skin surface. These epidermal ridges complete their permanent, individual patterns in the second half of fetal life [].

The Regulation of Epidermal Development

The process during which the unspecified surface ectoderm adopts an epidermal fate is defined as epidermal specification [].

Generally, keratinocytes take about 4 weeks to pass from the germinal layer to the outside of the body, and the epidermis structure depends on both their proliferation rate and differentiation processes. The fine balance among proliferation and differentiation is regulated by a complex system of interaction between many growth factors (Table ].

Table 1.1

Main growth factors involved in proliferation and differentiation of keratinocytes

Proliferative | Anti-proliferative |

|---|

EGF | TGF1 |

FGF | TGF2 |