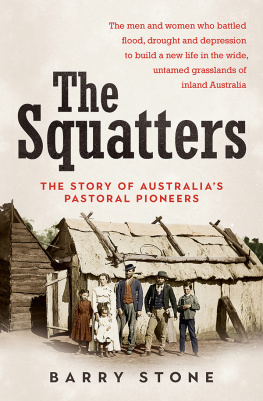

Also by Barry Stone

Secret Army (2017)

The Desert Anzacs (2014)

The Diggers Menagerie (2012)

The Almost Complete History of the World (with Joseph Cummins and James Inglis, 2012)

Scandalous (2012)

Mutinies (2011)

Great Australian Historic Hotels (2010)

Historys Greatest Headlines (with James Inglis, 2010)

First published in 2019

Copyright Barry Stone 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76029 153 2

eISBN 978 1 76087 017 1

Internal design by Midland Typesetters Australia

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Cover design: Luke Causby/Blue Cork

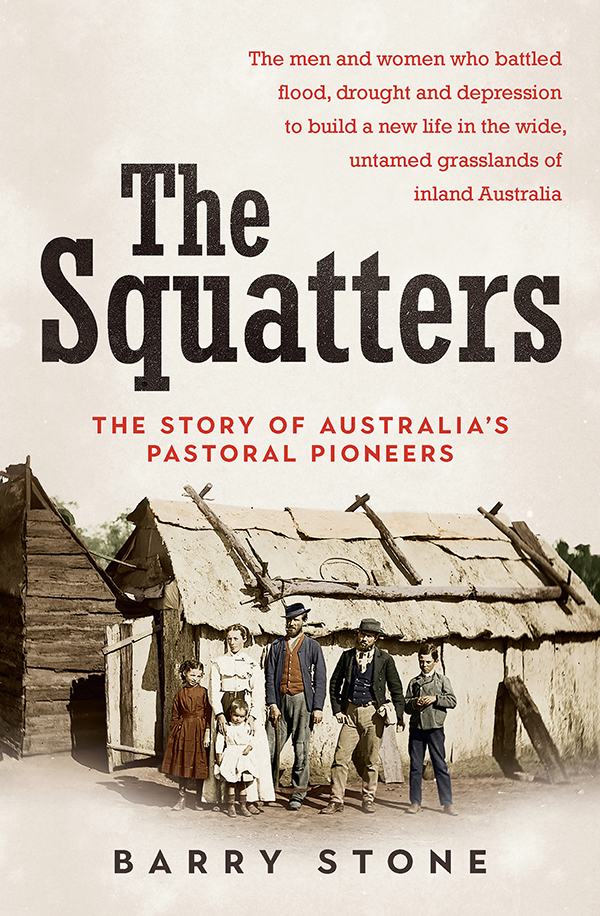

Cover photo: Family outside slab hut house, Gulgong; Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW

Dedicated to Yvonne, Jackson and Truman.

My beautiful family.

CONTENTS

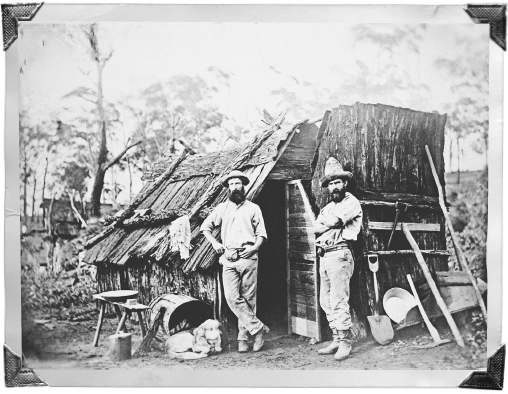

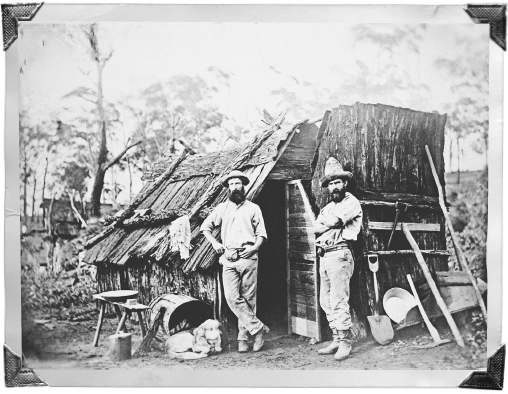

Workers outside their bark hut, Queensland c.1870.

Richard Daintree, State Library of Queensland

I remember a ball at the local town hall, where the scrub aristocrats took one end of the room to dance in, and the ordinary scum the other.

Henry Lawson, The Hero of Redclay, 1900

In July 1789, a Cornish farmer turned convict named James Ruse came to the end of his term of imprisonment. Guilty of the theft of two silver watches and other assorted property, he had been transported to New South Wales with the First Fleet a year and a half earlier, on board the three-masted cargo ship Scarborough. Four months after his term expired Governor Arthur Phillip, realising the importance of self-sufficiency for the new colony, permitted Ruse to work an acre of cleared land at Rose Hill near Parramatta. Having no animals, Ruse was forced to hoe the ground himself, into which he sowed bearded wheat and maize. In the absence of manure, he energised his soil with potash from the timbers he burned, and composted it with its own weeds and grasses. He produced such a healthy, albeit small, harvest that in February 1791 he declared himself self-sufficient. A few weeks later he was awarded a grant of 30 acres, a grant that became known as Experiment Farm. It was the first land grant in Australian history.

Food production was a constant preoccupation for the early British settlers. Arriving with no knowledge or experience of Australian soils, the land around Sydney Cove was thought to be only a shade shy of barren compared to the fertile English soils theyd left behind. By the Christmas of 1791, however, arable lands either side of the Parramatta River, including the land under cultivation at the Rose Hill farm, were increasingly being worked by emancipists (pardoned convicts) who were offered land grants so they could grow their own food and help lessen the colonys dependence on government stores.

Initially tents were the settlers most common form of accommodation, but these soon gave way to slab huts, which in turn were replaced by dwellings of sandstone and clay. The colonys first track, from Sydney to Parramatta, was finished in 1791, and three years later a road was laid to the Hawkesbury River and an early unsuccessful attempt to cross the Blue Mountains was made. Port Stephens was surveyed in 1795, and the following year came another try at crossing the seemingly impenetrable Blue Mountains, this time by the explorer George Bass.

The colony was growing with the arrival of every ship. Growing, too, was its need for food.

There were seven horses, 87 chickens, eighteen turkeys, nineteen goats, 35 ducks, 29 geese, five rabbits and 44 sheep on the First Fleet when it arrived in January 1788. Brought over solely as a food source with no thought given to the significance of their fleeces, the sheep were killed. Other factors combined to make the food situation in the new colony progressively more tenuous. In September 1788, the first crops failed to germinate because the seeds had overheated on the long sea journey. Beef and pork rations had already been cut, and fish was increasingly being used as a substitute source of nutrition.

In October 1788, HMS Sirius was sent to Cape Town in South Africa for more supplies. The ship arrived back in May 1789 with 56 tons of barley, flour and wheat. But by the end of the year rations for every Man, from the Governor to the Convict had to be reduced by two-thirds, although extra rations were given to gamekeepers and fishermen, those whose job it was to procure food. Work days were scaled back to a mere six hours of toil. The colony was edging perilously closer to famine.

There were also cattle on the First Fleet, but when a de-horned bull, a bull calf and four cows purchased in South Africa during the voyagethe new colonys entire stockwandered off from their yardage in what is now the citys Botanic Gardens, their disappearance was considered nothing less than a calamity. And not only for the luckless Edward Corbett, the convict hired to guard them who was later hanged for the theft of a smock. The itinerant beasts were not seen again until 1795, when a scouting party, spurred on by Aboriginal rock drawings depicting a familiar, de-horned animal, forded the Nepean River at Camden, climbed a small hill near Menangle, and to their astonishment saw a contented herd of 40 grazing cattle. By 1801, that same herd, now wild, had grown to between 500 and 600 head, and by 1804 had swelled to several thousand. Over time the herd disappeared, either having been slaughtered or blended with privately owned stock brought on later ships.

In 1801, that great pioneer of the Australian wool industry, John Macarthur, sailed to England to convince British wool manufacturers that New South Wales merino fleeces were the equal to the best in the world, which at the time were coming from Spain. His timing was fortuitous, as he arrived when wool manufacturers were fighting to repeal laws prohibiting the use of water-powered spinning and weaving machines. Macarthurs promise of fresh supplies of fine-grade wool led to those laws being abolished, paving the way for a serious ramping up of productionand demand. In the age before refrigeration, meat was unable to be exported and cattle were raised only for domestic consumption, so Macarthur was in no doubt as to which industry the colonists in New South Wales should be developing.

The land was beginning to forge a new identity. In 1804, the name Australia was used for the first time by Matthew Flinders. Three years later came Macarthurs first wool exports to England. In April 1809, Scottish colonial administrator and British Army officer Lachlan Macquarie was appointed governor of New South Wales, and under his eleven-year rule the colony transitioned from a penal colony to a free settlement. Soon after his appointment Macquarie announced the establishment of five new townsRichmond, Castlereagh, Pitt Town, Wilberforce and Windsor. Even then, whatever lay beyond the Great Divide of the Blue Mountains remained a mystery to the colonists.