T he ideas in this book were distilled from thousands of interactions and conversations Ive had with people Ive encountered over the years. And for each one of you, Im deeply grateful.

Much of the content in this bookand much of my current teaching, writing, coaching, and consultinghas its origin in the workshops that my teammates and Ive created to help people build better relationships. These teammates are among the most amazing leaders and friends in my life. Thank you to (in alphabetical order): Lisa Bohn, Leigh Carlson, Katie Franzen, Beki Grissom, Chris Hurta, Deirdr Jansen Van Rensburg, Amy Kranicki, Karis Reichert, Deb Shurtz, and Chrissie Steyn.

Thank you to the early readers of this manuscript who offered fantastic critique, coaching, and feedback. They are (in alphabetical order): Shane Farmer, Scott Gibson, Sue Hood, Sandy McConkey, David Mitchell, Sarah Riebe, and Deb Shurtz.

Deep gratitude to my dear friend, Dr. Andy Hartman, who not only read the manuscript and offered his professional insights, but also regularly encourages and coaches me through all that life brings.

A special word of thanks to the remarkable team at Nelson Books. As a first-time author, Im grateful for the extra doses of patience and direction provided by Jessica Wong and Sujin Hong. To my agent, Chris Ferebee, I thank you for your wisdom, guidance, and expertise, which led to the publication of this book.

The lions share of my gratitude goes to my life partner, primary editor, and wife, September, who has read this book, reread it, and then read it again. With each reading, she has offered monumental suggestions, rewrites, and edits. My work and this book would not have been possible without her ability to take another persons ideas and put them into intelligible words.

S cott Vaudrey is a retired emergency department doctor and pastor. He received his MD from the University of Washington in 1988, and MA in transformational leadership from Bethel University in 2005. After transitioning from medicine to ministry, he served as a pastor for sixteen years, helping people navigate their relational challenges. Today he splits his time between executive coaching and speaking to staff teams, businesses, nonprofits, and churches around the country about how to improve relationships and create thriving team cultures.

Scott and his wife, September, live in the northwest suburbs of Chicago. They raised five children and have three grandkidsand counting.

CONTENTS

Guide

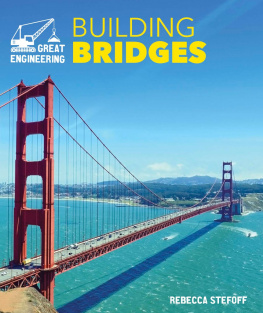

K nowing when to build a bridge (accepting) and when to set a boundary (protecting) is the trickiest part of navigating difficult relationships. And that is what this book is all about.

Imagine your twenty-nine-year-old son lives in your basement, plays video games all day, drinks too much, eats your food, works at a part-time minimum-wage job, and doesnt pay rent. His vocational aspirations seem limited to completing the next Grand Theft Auto mission, improving his Call of Duty infantry skills, and fine-tuning his Iron Man costume for the next Comic-Con. When do you set a boundary by insisting he either pay rent or move out? You may fear that setting a boundary too soonfor example, before he has time to find full-time employmentwould be unloving, but hes not even trying to look for a better job. Youre tormented by the questions: What kind of parent kicks their child out? Who wants that on their conscience?

Imagine your new mother-in-law constantly criticizes you and makes crazy demands on you but not on your spouse or anyone else on her side of the family. Your spouse is used to her behavior and doesnt notice whats going on. But you know you need to set a boundary, and you probably need to ask your spouse to take a more decisive role in protecting you. The question is when. If you set a boundary too quickly, you might alienate your new in-laws, cause added stress to your new marriage, be viewed as a prima donna by your relatives, or ruin the upcoming family barbecue. Who wants that kind of pressure?

Imagine your boss is demanding and insensitive. Although you love the work, you find yourself becoming increasingly resentful and unmotivated. You have a sense that you should say something, but the holidays are coming up and everyone is really busy. Plus, you think you might be up for a promotion soon. Do you risk being stuck in the same role forever or do you say something and risk getting fired? Who wants to enter the holiday season job hunting?

Imagine your friend is going through a hard time. Due to this, your relationship seems to be cooling, and your friendship feels distant. You know she is hurting, but at the same time, youre feeling hurt by the distance. You want to build a bridge of acceptance and move closer, but she is stressed, and you dont want to add to the burden by having a heavy, heartfelt conversation. Plus, you dont want to seem needy or risk being rejected further. Is now the right time to talk?

Imagine your spouse has a problem with anger or substance abuse. His well-established pattern looks like this: blow it, lie about it, get caught, apologize, and promise to do better next time; repeat. You set a boundary some months ago to protect yourself emotionally, and potentially physically, by telling him to move out. Now he seems to be taking responsibility for his life and changing his destructive behaviors. He has joined a twelve-step program, is seeing a therapist, and has not had an angry outburst or abused substances in months. Is now the time to start building a bridge of acceptance by letting him move back home? When is the right time to shift from setting a boundary (staying separated) to building a bridge? Is it too soon to give the relationship another chance? If he fails again, your kids will be heartbroken, and youll possibly lose their respect for letting it happen, not to mention youll be heartbroken too. Who wants that burden?

Having close relationships is tricky. German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer captured this reality in his parable the porcupines dilemma, which is paraphrased as follows:

A band of porcupines gathered on a cold winters day. To find relief from the coldin fact, to avoid freezing to deaththe porcupines began to huddle closer together. Their shared warmth brought relief from the chill in the air, but the sharpness of their quills caused each other pain. Soon, the discomfort brought about by close proximity caused the porcupines to move further away from one another. This brought welcomed relief from the painful pokes and stabs. But soon the porcupines began to grow cold.

This dilemma illustrates the tension of intimacy and relationships. If we want to have relationships with others, we must develop and hone our ability to move closer to others, despite the danger of their quills. But there are times we must learn to move farther away, despite the risk of experiencing the cold. This metaphor highlights the necessity of establishing an effective balance between building bridges (accepting) and setting boundaries (protecting).

Relational pain is common to us all. I certainly dont argue this reality. Yet I often behave as if this is only true at a theoretical level. If Im honest, what I really believe is that relationships are difficult for other people. When I experience relational pain, I cry foul; I am shocked and indignant, convinced that there must be some cosmic mistake.

Eugene Peterson, author and theologian, captured this tension beautifully:

We somehow have ended up a country full of Christians who consider suffering, whether it comes in broken body or in broken heart, a violation of their spiritual rights. If things go badly in body, or job, or family, they whine and complain endlessly.