We dedicate this book to significant others:

Bob Bechtle

Michele Respaut and Michle Sarde

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The idea for this book originally took shape in conversations between Shari Benstock and Isabelle de Courtivron. Sharis vision has remained indispensable to its successful completion and we would like to acknowledge with deep appreciation her invaluable support and advice.

Our contributors friends and colleagues stayed faithful to the project throughout its sometimes rocky history. Without their commitment, their hard work, and their unswerving belief in the value of collaboration and partnership, there would be no book.

Many others have supported and aided us in this venture. Much of the final MS preparation took place at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology during the summer of 1992. Kim Reynolds, Zachary Knight, and Bob Aiudi in the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures were invaluable to us. Special thanks go to Bob who tirelessly and cheerfully led us through the labyrinthine passageways of computer technology. Philip Khoury, Dean of Humanities and Social Sciences at MIT, provided financial support at a critical moment. Ruth Perry and Susie Sutch read and commented on early drafts of the introduction.

Finally, our experience of working together on this book has reconfirmed our belief in collaborative endeavor as both fruitful and fun.

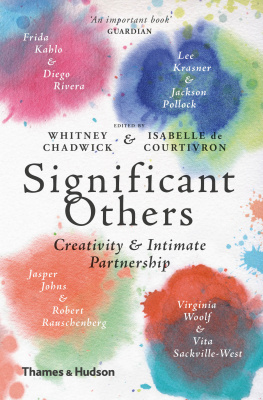

Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include:

The Militant Muse: Love, War and the Women of Surrealism

Portrait of the Writer: Literary Lives in Focus

Seeing Ourselves: Womens Self-Portraits

Women Artists: The Linda Nochlin Reader

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

Contents

Anne Higonnet

Whitney Chadwick

Isabelle de Courtivron

Lisa Tickner

Louise Desalvo

Susan Rubin Suleiman

Hayden Herrera

Judith D. Suther

Nol Riley Fitch

Bernard Benstock

Jonathan Katz

Ronnie Scharfman

Anne M. Wagner

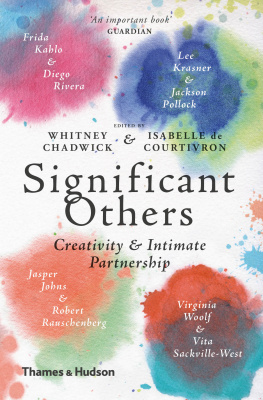

This book is a collective attempt to tackle the questions of gender and creativity from a different vantage point. Traditional biographies and monographs have typically described creativity as an extraordinary (usually male) individuals solitary struggle for artistic self-expression. We decided, instead, to explore the complexities of partnerships and collaborations, painful as well as enriching. We chose to focus on couples (whether different or same-sex) because couples are endlessly fascinating in the diversity of their interactions. And we further chose to limit ourselves to couples in which both partners were either visual artists or writers in order to have a shared creative context within which to explore differences arising from gender, sexuality, age, race, and class. Finally, we wanted to be restricted by neither the anecdotal nor the theoretical. With these parameters in mind, we asked the following question of the thirteen contributors to this book: if the dominant belief about art and literature is that they are produced by solitary individuals, but the dominant social structures are concerned with familial, matrimonial, and heterosexual arrangements, how do two creative people escape or not the constraints of this framework and construct an alternative story?

We expected the answers to this question to establish a decipherable pattern of constraint and prejudice, of male genius and female absence. But the essays that came back to us from our contributors surprised us. While fully taking into account the limitations of gender stereotyping, their essays provided us with a renewed sense of wonder at the endless complexities of partnership itself.

These stories can be told anew today as a result of a generation of theoretical writings that have taught us to view gender and creativity through new frames. The work of many scholars has been crucial in this respect. For over twenty years, literary and art critics have been motivating us to read with fresh eyes. More recently, a new wave of writings has focused on groups, interactions, friendships and mutually enriching influences, which blur our existing notions of heroic individuality. Literary scholars Ruth Perry and Martine Brownley, for example, have explored a process that they call mothering the mind, which retrieves from silence and absence those who helped create the conditions, the inspiration, and the atmosphere for their partners artistic production. Another mode of investigation has led to a closer scrutiny of those creative women who were formerly considered disciples and imitators of great men, and it has brought their stories and their art to life, at times with persuasive subtlety, at others accompanied by powerful indictments. Setting the record straight, which began with Nancy Milfords poignant biography of Zelda Fitzgerald in 1970, has more recently liberated Frida Kahlo, Camille Claudel, Berthe Morisot, and others, from the shadows of their spouses, teachers, lovers and mentors. A new generation of biographers has asked unprecedented questions about the reciprocal influence of couples such as Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, or Georgia OKeeffe and Alfred Stieglitz and in doing so, has taken us a long way toward the dismantling of earlier stereotypes. Phyllis Roses discussion of five Victorian couples in Parallel Lives (1983), and Shari Benstocks account of a community of women writers in Paris in the early years of the twentieth century, Women of the Left Bank (1986), opened our eyes to the complex social formations that shape creative lives. More recently, Patricia OTooles The Five of Hearts: An Intimate Portrait of Henry Adams and His Circle (1990) and Humphrey Carpenters The Brideshead Generation: Evelyn Waugh and His Friends (1990) are among the works which have extended our awareness of the rewards and costs of intimate friendships. In that same spirit, a number of the contributors here point to the ways that couples like Anas Nin and Henry Miller, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West, Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, Simone and Andr Schwarz-Bart, Lillian Hellman and Dashiell Hammett, and Robert and Sonia Delaunay redefine previous gender and sexual stereotypes, and point toward models of far more fluid, equitable and enriching partnership.

The essays in Significant Others suggest that although most of the artists and writers concerned have not escaped social stereotypes about masculinity and femininity and their assumed roles within partnership, many have negotiated new relationships to those stereotypes. Perhaps because as feminist scholars we have until recently focused on the social constraints, we have not fully understood the richness of the private interactions that operate within relationships. Our contributors pay equal attention to the theory underlying the social concepts of masculinity and femininity and to the real social and material conditions which enable, or inhibit, the creative life. The lives of Camille Claudel and Auguste Rodin, for example, remind us that in assessing their careers we must pay attention to social constructions of sexual potency or madness,

Next page