For Fay Young

This eBook edition published in 2013 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2010 by Birlinn Ltd

Copyright Ray Perman 2010 and 2013

Excerpts from the work of Kathleen Raine are printed by permission of the literary estate of Kathleen Raine.

The moral right of Ray Perman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

eBook ISBN: 978 0 85790 078 4

ISBN: 978 1 78027 120 0

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Version 2.0

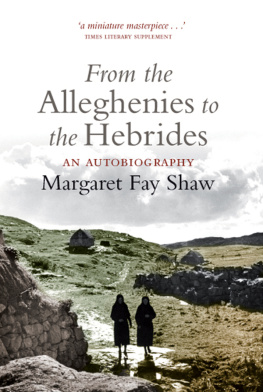

List of Illustrations

Foreword: The House of Contradictions

The owl-lamp on the Steinway grand, quartos

Of Schubert, Mozart, Moores Irish Melodies,

The carved funny animals, the barque under glass,

The curious mirrors of carved bones

Made by the French prisoners in Edinburgh Castle,

Books on birds and minerals, cases of butterflies,

The family miniatures on ivory, piles

Of the New Yorker, Paris Match, The Scotsman,

The friendly bottles, ash-trays, cigarettes,

The cat-clawed Chippendale and the dog-haired cushions, photographs

Of Uist and Barra and of distant friends, all this

Learned and happy accumulation, held together

By the presence of John and Margaret Campbell.

The poet Kathleen Raine, waiting to play her card, recorded a small part of the vast clutter that greets visitors to Canna House and found clues to the character and past of the buildings owners. Many items were probably in the same positions they had occupied 28 years earlier when she had first visited the island. They are still in place today an eclectic collection made over long lives of curiosity, inquiry, action and compassion.

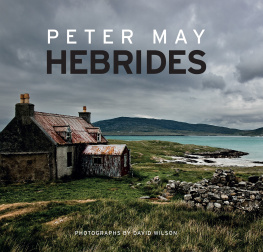

I first saw that room in 1977, the year before Raine wrote those words. Arriving in Canna by boat from Mallaig on a clear spring day, it made an impression like no other place I had been an island of contrasts. On the north side, cold blue shadows cast on the sea by 600 foot cliffs. On the south, warm sunlit meadows of vivid green. Organ-pipe columns of hard basalt granite, soft beaches washed by a clear sea one of white sand, another of black.

The man who had fallen under the islands spell 40 years before and against formidable odds had bought it and nurtured it, was waiting for me on the pier. John Lorne Campbell, leaning on a shepherds stick, was dressed in a shabby tweed jacket and a black beret that appeared too big for him. While other passengers started to walk along the unmade road, John ushered me into an incongruous blue Volkswagen Beetle for a journey of just a few hundred yards to the front of the imposing stone mansion visible from the water. He answered my questions tersely, but otherwise made no conversation.

You cannot see Canna House from its gate. A dark tunnel of Escalonia bushes, which have been allowed to grow so they meet overhead, hides the view until, emerging into the sunlight, the house is square before you. Leading the way up short steps and through an oak door with a dolphin knocker, John Campbell hung his beret in the porch alongside several other hats which included a conical straw sun-shield of the type worn by Chinese workers in paddy fields and a solar topee, the pith helmet beloved of the British Raj. I found later that John wore different hats for different tasks. On the floor was a croquet set, in a corner fishing rods, nets and a pendant flag from the top of a buoy.

I had only seconds to take in the enormous two-handed broadsword leaning in the corner of the hall, the glass cases standing on a cupboard one containing an aneroid barometer continuously recording atmospheric pressure on a roll of paper, the other a stuffed Spoonbill. A red and white ships lifebelt leant against a far wall. A printed sign on a door ordered: Quiet. Hangover Zone. We passed quickly through the dining room, which would have been elegant with silverware on a mahogany sideboard, white marble fireplace and portrait of a red-coated general presiding over the table, were it not for the carved and broken slabs lying on the floor of the window bay, like toppled tombstones.

I was greeted by Margaret, the antithesis of her husband: he tall, upright, reserved; she small, warm, welcoming. But John had not paused and I followed him down two steps to a large room with windows facing the garden. There were then, as there are now, filing cabinets, boxes and piles of papers on a large rectangular surface, which on closer inspection proved to be a billiard table with a wooden cover over the baize. The far wall was covered with charts of the seas around the island still there, but now yellowing. There was another stuffed bird, a capercaillie, a stack of the satirical magazine Private Eye, a fax machine, a telephone and a photocopier. John, I learned later, loved technology. He was what would be called today an early adopter. This was before the internet age, but with a typewriter, fax and copier he was connected to the world.

I was a journalist come to get a story on ferry policy. Dr Campbell, as I always called him, was campaigning vigorously against the Small Boat Scheme, a proposal to replace the ferry which provides the island with its lifeline to the mainland with a service of light craft run from a nearby island. It had set him against not only his neighbouring proprietor on Eigg, but an array of bureaucrats and politicians.

He was clearly energised by the fight, eager to explain his argument. As a Financial Times reporter, I was trained to demand precise numbers and verifiable facts. I had expected anecdote and prejudice from the eccentric laird of a remote island. Instead I got a folder of official documents, transcripts of evidence, and details of the class of passenger certificate required for a vessel crossing the Sound of Canna (which, John explained, has more exposed seas than those on the more sheltered side of Rum facing the mainland). He had tabulated the exact number of days during each of the past few years on which the ferry had been unable to sail because of bad weather.

Listening to him and reading the evidence I became convinced that not only would the Small Boat Scheme be a disaster for Canna, but that by backing it, the Highlands and Islands Development Board was going against its own policy. How could they not see this themselves? I asked. The answer was damning: Because they are not practical men.

The John Lorne Campbell I first got to know was nothing if not a practical man. At the age of 70 he was still a working farmer and fisherman, running a business in a location which presented daily challenges that town and city-dwellers never have to face. I learned only later that he was also a scholar who had devoted a second lifetime to the Gaelic language and a third to the study of butterflies and moths.

In the years that followed, I got to see more of the house. To sit where Kathleen Raine had sat, not playing cards but listening to Margaret playing the piano, John the flute and visiting musicians the violin and cello. To see the books, not just the library (the Hangover Zone) of books, papers and recordings, but in every room and on shelves lining every corridor and landing. The more I learned, the more I became intrigued by the puzzles.

Next page