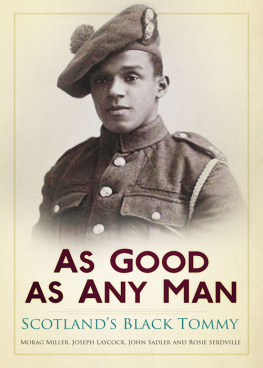

Arthur William David Roberts (18971982)

One hundred years have passed,

Still the blame goes on,

No black no white,

No good no bad,

There stood glory,

There fell fate,

Where was sense,

Where was shame,

But never forget,

Those who gave,

Their todays,

For our tomorrows,

Nor those who lived,

And bore the scars for life.

Roy Laycock: 1914 (2012)

CONTENTS

This book could never have been written without the detailed research and background work undertaken by Morag Thomson Miller and Roy Laycock. It is their dedication and diligence that has steadily built up Arthurs story from the time of its chance discovery. Thanks are also due to Chloe Rodham for the maps, Ian Martin, curator of the Kings Own Scottish Borderers Museum in Berwick, Murray Miller, Laura Smith, the owners of Arthurs memorabilia, Doreen Thomas, Darryl Gwynne and family, Lauren Crooks, Ian McCracken, Rita Thomas, Craig Fleming, Tony Sharkey, Steve Wallwork, Marc Rath, James Beal, Sarah Taylor, Janet Hiscocks, the Bristol Archivists, Karen Greenshields, Ruth Alexander, Izzy Charman from Media, Allison ONeill, Jim and Isa Wilson, personal acquaintances of Arthur, Alan Bullas, for photographs, Glasgow Registry Office, The Mitchell Library, Glasgow, Thos Robertson, Wendy L.T. Miller, Christine Hughes, Jane Rafferty, Sandy Leishman, Bob Steele, Pat Docherty, Frank Leonard, Gus McPherson and Jean Mackenzie, staff at the Glasgow City Archives, Jim Fleming, and, finally, to Mark Beynon and the editorial staff at The History Press for another successful collaboration.

***

I should like it to be clearly understood that in writing this miniature book of sketches, I lay no claim whatever to possess any literary abilities (Arthur Roberts).

Likewise, any errors or omissions are entirely the responsibility of the joint authors.

Rosie Serdiville, John Sadler, Morag Thomson Miller and Roy Laycock

October 2013

INTRODUCTION:

THE FORGOTTEN

In the autumn of 2004, two young people purchased a house in Mount Vernon, a residential suburb of Glasgow. They had no expectation of undiscovered treasure but there, in the uncleared attic, they found it. Behind a Dansette turntable they discovered a cardboard box. And in that box was Arthur. Arthur William David Roberts, who had died over twenty years previously and whose life story, like a time capsule, had lain forgotten ever since. Here, in his diaries, pictures and memorabilia, was the record of his life. At the core of Arthur lay his war experience; the record of a man who had lived through the cauldron of Flanders during the Third Battle of Ypres in 1917:

For so short an army career, I think I may safely say, my life during that period was as varied, and eventful, as most private soldiers of a similar length of service. A soldier during war time if capable is pushed into many breaches whether fit for the front line or base. I have been fit for both; consequently I have filled many breaches. The last sentence will perhaps lead the reader to think I am possessed of great capabilities, and this belief may be strengthened when I say that I have been company-runner, batman, guide, dining-hall attendant, bugler, cycle-orderly, dispatch clerk, bomber, motor mechanic, telephone orderly, aircraft-gunner, hut-builder, stretcher-bearer, and one or two other things. Now it has been unintentional, if I have seemingly blown my own horn about my military accomplishments, but I think this book, written as frankly as I could write it will exonerate me from any imputation of self-aggrandisement.

The strange thing about it is, that according to my discharge, my military qualifications are Nil. At that rate, I think nothing short of being a Commander-in-Chief, allows me to have a military qualification.

There is yet another very strange thing, but this also puzzles me. I have volunteered for detachments, sniping jobs etc., but when the orderly sergeant was looking for volunteers for church parade, Pte. Roberts was talking scandal in the latrine, or was attacked with a generous fit, and was carrying water for the cooks.

Should the parade be compulsory, the same Pte. fell in the extreme rear, trusting to luck that the church hut or tent, would not hold the lot.

The story is a remarkable one. Arthur Roberts was born in Bristol in 1897 of mixed-race parents. David Roberts (Jenkins), his father, a ships steward, hailed from the Caribbean. His mother, Laura Dann, was a West Country lass. By the time of Arthurs birth, the family had dropped the surname Jenkins. At some point in the early twentieth century it appears Arthur and his father moved to Glasgow, where the young boy was educated. Remaining at school well beyond the normal leaving age of 14, it is clear from the quality of his prose that he was a highly intelligent and articulate young man. The photographs show us a bit of a dandy: he looks directly and confidently out at the world, a young man of style, who invites our interest traits that would be apparent all his life.

The adult Arthur was a marine engineer who worked for some of Glasgows largest and most important engineering firms: Harland & Wolff and Duncan Stewart (later Davy United). He volunteered in February 1917, first with the Kings Own Scottish Borderers, then, in June of that year, with 2nd Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers.

Arthurs story is not just another set of Great War memoirs, adding to the considerable volume that already exists, but a unique record from the viewpoint of a mixed-race soldier. Relatively few black soldiers served in a front-line role with Scottish regiments in the First World War. The conflict consumed many lives in Scotland and her proud regiments garnered many laurels won at a very high price. Arthur Roberts does not dwell on his race or cultural identity he is very much an individual, both participant and wry observer, slightly detached, while clearly not, in any way, excluded.

Accounts by black soldiers are very rare in Scottish literature. And yet Arthurs narrative is very much a Scottish experience, regardless of the writers origin. It is extremely well written and beautifully illustrated; the writer was an accomplished artist. It is more than just a war memoir, it is a fully rounded account that has been ably illuminated by Morag Thomson Miller and Roy Laycock, who have painstakingly researched the subjects life history. They know Glasgow intimately as natives and a great part of Arthurs story is his life as an adopted Glaswegian:

I first actually entered the trenches on the dawn of 9th June, 1917. I can tell you, after our gruelling march [described in the diary], I was a physical wreck. That night as I plumped down in a dugout, I was so tired that without taking off my equipment, I almost immediately fell into a trance. All the Kaisers horses and all the Kaisers men could not have put the wind up me that night. No, I was too far beyond the stage of self-preservation. Sleep and welcome oblivion was wanted. I believe I should not have cared if I had been told I should never wake up again.

Every year, Remembrance Day on 11 November becomes a more self-conscious event now almost Disneyfied in the contemporary slush of sentimentality. No future generation will have the privilege of hearing, in person, the voices of those who served, as the last known survivors have died. This marks a watershed, when the conflict passes beyond immediate consciousness, past a memory of fathers and grandfathers, and grows increasingly remote.

Next page