Contents

A LL DESCRIPTIONS OF hipsters are doomed to disappoint, because they will not be the hipsters you know. Yet someday when hipsters no longer walk the earth, and subcultures have changed, and new aesthetics have evolved, with new terms of disapprobation and praise, the hipster of the period 19992010 will remain of historic interest and investigators at a later date will be at the mercy of whether or not we chose to record our impressions today.

I am reminded of a liberty a friend once took with me. Have you ever heard of Ali G? he asked. No, I answered. Great, just listen to me do his routines my impression of hims perfect .

Those of you who have encountered hipsters in real life, in other words, may surely complain of the characterizations in this book. But to those of you who are reading this in 2050, I can only say: Everything in this book is true, and its impressions are perfect.

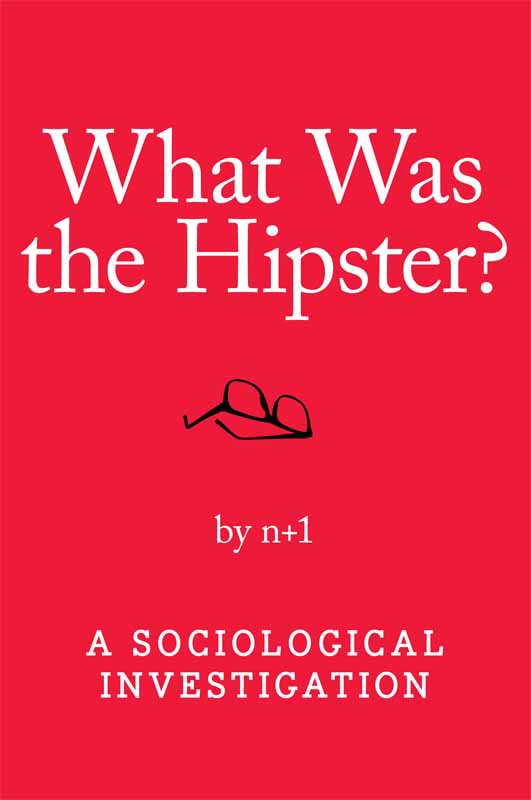

T HE PURPOSE OF What Was the Hipster?: A Sociological Investigation is to find out if it is possible to analyze a subcultural formation while it is still happening, from the testimony of people who are close to it. We used the collective knowledge of a very idiosyncratic group of people: readers of and writers for the journal n+1 , plus interested strangers, at a panel held at the New School; then, after the event, journalists and other critics to whom we gave the early transcripts, so they could challenge our approach and disagree.

Participants were welcome to exploit their own immediate experience and knowledge, their scholarly and analytic inclinations, and whatever bad motives and resentments they no doubt harbored toward ex-neighbors, rivals, or people who dress better or more expensively, to add to a record of a single stereotype and bogeyman the modern hipster who has environed us all for more than ten years, at the precise instant that this figure may be changing.

The metamorphosis of the hipster if it is real involves a word that has been used for insult and abuse gaining a neutral or even positive estimation in the culture. It accompanies the sense that hipster fashion has entered the mainstream as a set of style accessories repackaged for purchase in shopping malls across America, but also that the deeper social impulses that helped create the hipster as well as the vitally necessary impulses to impugn hipsters have gone global, mushrooming in Europe and Latin America, too.

It is not possible to say that the hipster is dead perhaps you know some, perhaps youve seen them eat and sleep but the fact that one begins to hear visitors to cafes in Williamsburg or on the Lower East Side describe themselves or their friends as sort of hipsters, you know, suggests it may be time to round up the original targets early history, and the words original hostile meanings, before it is too late.

H IPPIE A TERM of abuse invented by hipsters or beatniks of the postwar generation for little hipsters, who just liked to dance and smoke pot but knew nothing about jazz or politics or poetry became available to mass media in the mid-1960s, thus attracting new, young converts to the lifestyle, until the different sorts of younger people now correctly called hippies (who had known themselves as freaks, or heads, or possessed no name) accepted it, too, and even found it useful as an identifier (You dig, its like a hippie shirt.).*

* This, anyway, is the story familiarly told. See Charles Perry, The HaightAshbury: A History (New York: Random House, 1984), 5-6, a pop account based on an impressive wealth of interviews with key protagonists. One additional description from Perry of early, pre-1965 hippie derogation and style may be notable because of its surprising echoes with the charges against modern hipsters: Another grievance was that while Beats were always down and out, the hippies seemed to have money.... What was unique to hippies was their attitude an expansive, theatrical attitude of being cool enough to have fun. They called themselves dudes and ladies rather than cats and chicks. Unlike Beats in their existential black and folkies in their homespun and denim, they wore flashy Mod clothes.... Hippies were scattered around in other places in the country, too [besides San Francisco, their birthplace], mostly near college campuses. This certainly sounds a lot like present-day hipsters, and it clearly precedes the later identification of hippiedom with the politics of the anti-war and peace movements.

Could we be at a point with the hipster as significant as that one? Presumably not. Surely a subcultural moniker cant be of immense importance twice. The word hipster comes out of the distant American past, as the name for a previous, truly significant subculture. A main line of our investigation into contemporary hipsters takes up the central concern of that earlier figure, the 1940s and 1950s-era hipster namely, race, as blackness and whiteness, source of knowledge and ground of resistance, from before the Civil Rights era through our supposedly post-racial era and asks how the old name came to be taken up again.

Hipsterism as an identifiable phenomenon also very clearly has to do with particular fashions, and fashion micro-trends, which are notoriously hard to explain. The question of which exterior markers are essential to the hipster, and where they came from and what they mean, clearly drives people most to distraction in these pages. Yet one begins to get hints, thereby, of what is at stake in matters of distinction, and self-love, and superiority around such differences and, maybe more importantly, how supposedly inexplicable fashion details (like the trucker hat or ironic T-shirt), at their origins, actually signified very obvious, precise, and near-articulate things about who one fantasized oneself to be, or apologized for, or envied especially as these fashions duplicated elements of the past, allowing forms of communication and reinforcement of ideology. Thus fashion details may be more explicable than they seem. One begins to wonder if, more generally, the claim of their arbitrariness is a matter of mystification, and a refusal to trace them to their first wearers or proponents.

We proceeded in our investigations as follows. On a Saturday afternoon in spring 2009, an initial symposium and discussion took place, announced in advance and advertised to the public, at the New School in Manhattan. This book reprints the original papers offered for discussion though the centerpiece of this book is clearly the lengthy floor debate and discussion that followed. We have resisted the impulse to correct mistakes by the panelists (though a few factual errors are annotated).

Two of the more extensive reportorial accounts of the event follow, in a section called Dossier, giving a feeling for how the effort was initially received. In the months after the panel, the editors sent transcripts to commentators who we believed might question or dispute the proceedings so far, opening the topic up in new ways. The section with their remarks is titled Responses. At this point, the organized investigation should spill over into the readers domain you, the reader, will have your own sense of where an inquest into the hipster will need to go next, and where you, yourself, disagree. A final section of Essays, however, offers more considered and detailed articles on particular sub-topics of the field, or expansions into the hipsters contact with the world beyond him taking up the hipster Other (a.k.a. the douchebag), hipster race, hipster gender, hipster aesthetics, and the hipster future.

F OR ONCE, HERE is analysis of a cultural phenomenon not learned from TV, or pre-digested. Thank god for that: when one investigates the record of any subculture, one sees how thoroughly past moments get summed up and misrepresented by intellectual annexations, money-making efforts, second-order media replicas, and latecomers. As if hipsters were Norman Mailer, the hippies were Woodstock, punk were the Sex Pistols, or grunge were Kurt Cobain! Yet each of these manufactured phenomena, because of their superior access to wider publicity strategies and capital (and film , crucially, alongside recorded music the most important medium of subcultural transfer), became instrumental in the reproduction of genuine impulses of resistance and hope across generations.

Next page