Springer Science+Business Media New York 2015

Christopher R. Shea , Jon A. Reed and Victor G. Prieto (eds.) Pathology of Challenging Melanocytic Neoplasms 10.1007/978-1-4939-1444-9_1

1. Gross Prosection of Melanocytic Lesions

Introduction

Accurate diagnosis of a challenging melanocytic neoplasm requires adequate (i.e., representative) clinical sampling of the lesion and careful microscopic examination of histological sections. Adequate microscopic examination of a lesion in turn depends on the proper transport, gross prosection, and tissue processing of the clinical specimen to assure optimum histology. These technical considerations also are important to preserve tissues for additional immunohistochemical or molecular diagnostic studies if required. As such, tissue handling is becoming an increasingly important variable as newer, more sophisticated molecular tests are developed to provide better diagnostic and prognostic information and to identify specific aberrations with actionable treatment options for individual patients. Many of the newer molecular diagnostic tests have been developed for use on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues []. The objective of this chapter is to summarize current best practice techniques for the gross examination and prosection of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded cutaneous specimens containing melanocytic lesions.

Biopsy/Surgical Techniques

Proper handling of tissues containing melanocytic neoplasms requires an understanding of the types of specimens commonly submitted to the laboratory for pathologic examination. Most cutaneous specimens can be divided into two broad categories: diagnostic biopsies and therapeutic excisions. Cutaneous melanocytic lesions often are sampled first by shave biopsy or punch biopsy to establish a diagnosis. Subsequent (or primary) therapeutic procedures may include deeper shaves (tangential excisions/saucerizations), larger punches, and deeper elliptical or cylindrical surgical excisions. Melanocytic lesions are seldom intentionally sampled by curettage because of diagnostic limitations related to tissue orientation in histological sections.

A considerable body of literature already exists concerning the benefits and limitations of frozen section diagnosis of melanocytic lesions treated by Mohs micrographic surgery in a clinical office setting and will not be further discussed in this introductory chapter. Similarly, diagnostic and therapeutic procedures (such as needle core biopsies, fine needle aspiration cytology, surgical de-bulking procedures, and regional lymphadenectomies) commonly used to evaluate extracutaneous deposits of metastatic melanomas are not included. The handling of sentinel lymph node biopsies related to the challenging differential diagnosis of metastatic melanoma versus capsular nevus is addressed in Chap..

Punch Biopsies/Punch Excisions

Punch biopsies of skin produce a cylindrical portion of tissue that is oriented perpendicular to the epidermal surface. Punch biopsies often are performed to diagnose inflammatory dermatoses because they allow histological examination of epidermis, superficial and deep dermis, and possibly superficial subcutaneous adipose tissue. Similarly, a punch biopsy may be used for a melanocytic lesion that is suspected of having a deeper dermal or subcutaneous component. Larger punches also may used to completely remove a lesion that was previously biopsied by a smaller diameter punch biopsy or by a superficial shave biopsy (see below).

Small punch biopsies should be used with caution when sampling a melanocytic neoplasm []. A single small punch biopsy may yield a nonrepresentative sample form a large atypical melanocytic neoplasm. Multiple smaller punches may be used; however, to map peripheral spread of a large lesion such as lentigo maligna that has previously been diagnosed by another biopsy.

Handling of a punch biopsy is straightforward. Punches intended to completely remove a lesion should be marked with indelible ink along the entire dermal surface including periphery and base, sparing only the epidermal surface. Specimens larger than 3 mm in diameter are bisected, and very large specimens, serially sectioned along the long axis (i.e., perpendicular to the epidermal surface). After routine tissue processing, histological sections cut perpendicular to the epidermis will thus have a perimeter marked by ink that defines the surgical margin (Fig. ).

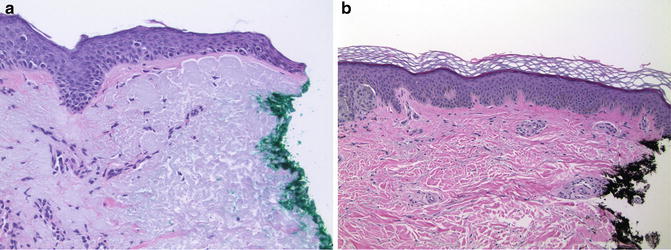

Fig. 1.1

Microscopic evaluation of peripheral margins. ( a ) Melanoma in situ involving the inked peripheral margin of a specimen (20). ( b ) Atypical nevus excised with a margin of un-involved skin (10)

Shave Biopsies/Shave Excisions (Saucerizations, Tangential Excisions)

Shave biopsies represent a sampling of epidermis and superficial dermis taken in a plane parallel to the epidermal surface. Deeper shaves may include superficial reticular dermis, but subcutis is almost never sampled by this technique. Deeper shave biopsies (tangential excisions/saucerizations) intended to completely remove a lesion are marked with indelible ink along the entire margin sparing only the epidermal surface. Depending on the size, shave biopsies may be bisected along the long axis or serially sectioned. The tissue is then embedded on edge so that the inked peripheral and deep margin is entirely represented in the histological section. Larger shaves may be divided between cassettes so that the tip (third dimension) margins can be evaluated independent of sections from the middle of the lesion.

Elliptical (and Cylindrical) Excisions

Excisions are, by definition, specimens intended to excise a lesion. As such, assessment and reporting of margins is usually required. Most excisions are elliptical; however, cylindrical specimens may be taken from certain anatomic sites where optimum lines of surgical closure are not clinically evident prior to the procedure. In this case, additional detached tips (dog ears) may be submitted separately, and should be treated as true tip margins. Larger excisional specimens often are oriented to identify a specific anatomic site on the patient such that a positive margin may be treated locally and less aggressively. Any surface lesion should be described noting its size, circumscription, color(s), and proximity to the peripheral margins.

Un-oriented specimens are marked with indelible ink along the entire peripheral and deep surgical margin similar to a shave biopsy. The ellipse (or cylinder) is then serially sectioned along the entire specimen (bread-loafed) to produce parallel sections perpendicular to the epidermal surface. Each section should be no greater than 23 mm in thickness to facilitate optimum tissue fixation and to allow examination of a larger area of surgical margin. Any lesion present on the cut surface should be noted, especially satellite lesions outside of the prior biopsy site in larger excisions.