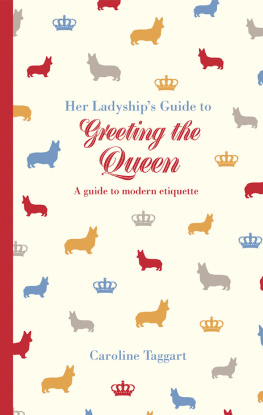

HOW TO GREET

THE QUEEN

and other questions

of modern etiquette

HOW TO GREET

THE QUEEN

and other questions

of modern etiquette

CAROLINE TAGGART

For Ros,

who understands Her Ladyship

better than anyone

An Introduction to Her Ladyship

Her Ladyship emerged from genteel obscurity in 2010 with her Guide to the Queens English, in which she took readers by the hand and led them soothingly through the minefields of basic grammar, clichs and confusables. Since then she has published her views on Running Ones Home and The British Season, with advice ranging from getting grass stains out of cricket whites to the unwisdom of wearing heels so high they prevent you, heaven forbid, from walking or from curtseying elegantly.

Caroline Taggart has been Her Ladyships amanuensis since the beginning. In her own right she is also the author of the best-selling I Used to Know That, The Book of English Place Names, The Book of London Place Names and most recently a venture into the world of cake, A Slice of Britain. She is also co-author of the highly successful My Grammar and I (or should that be Me?).

Acknowledgements

Her Ladyships friends are always a rich source of anecdote when she is conducting her research: special thanks this time to Lorraine, Airdre, Ana and Rebecca for their contributions, and to the various strangers on whom she has eavesdropped, particularly the badly behaved ones. Thanks also to Kristy, Peter and the team at Anova and the National Trust.

Contents

INTRODUCTION

Nothing more rapidly inclines a person to go into a monastery than reading a book on etiquette. There are so many trivial ways in which it is possible to commit some social sin.

QUENTIN CRISP (190899)

Mr Crisps fears may be exaggerated, but there is no denying that choosing how to behave in unfamiliar situations is one of the many minefields with which modern life abounds. Etiquette has been defined as the customs or rules governing behaviour regarded as correct or acceptable in social life or, more fancifully, the key that opens the doors to greater social happiness. Its easy to think of it as old-fashioned at best and absurd at worst: after all, etiquette books from bygone days include such antiquated advice as what drinks to serve at afternoon whist parties (Sherry and claret cup can be provided in addition to tea and coffee) or the correct way of raising a top hat (The unmannerly habit of touching the hat, instead of lifting it, is an indication of sheer laziness and a lack of gallantry).

Until as recently as sixty years ago, in the days when young debutantes still made their curtsey to the reigning monarch, etiquette was drilled into the head of every child to whom it was likely to have the remotest relevance. When the time came for them to go out into the world, they would know the correct approach to every occasion, whether they were writing a letter to a friend or being presented to a visiting Ambassador. But as more and more informality has seeped into most aspects of life, so we have lost the training that produced that almost instinctive polite behaviour. To a large extent, many of us would say, this doesnt matter, because we give fewer afternoon whist parties and raise fewer top hats, write fewer letters and meet fewer Ambassadors than our grandparents did. But it does mean that every now and again when we are invited to a smart wedding, for example, or come into contact with the Royal Family we are unsure what is expected of us. It is partly to help the nervous to cope with occasions such as this that Her Ladyship offers the advice in this book.

Mention of the Royal Family reminds her that its members are probably more carefully drilled in etiquette than anyone else in Britain today, although some of the younger element seem to be pushing back the boundaries between them and us and taking a more flexible approach to their own roles. Where relevant, therefore, throughout the book Her Ladyship will consider the Royal Aspect whether traditional or modern of dealing with a potentially awkward situation.

Etiquette is not confined to replying to invitations, arranging the glasses on the table for a ceremonial dinner and dressing appropriately for Henley Regatta. Some of the rules governing these matters have remained the same for generations; they may seem to the jaundiced modern eye to have no rational explanation, except that they have always been so. But the other aspect of etiquette is the sort of simple good manners that relies on consideration of other peoples wants and feelings; and this needs to adjust in order to cope with modern circumstances. It has been said that manners resemble language and fashion in that they adapt themselves effortlessly to social change; Her Ladyship would add that every now and then there comes along a social change that requires the invention of a new set of rules. (The fact that the Duke of Cambridge feels able to take part in an impromptu rock concert in a way that one can hardly imagine the late Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother doing shows that even Royal etiquette can and does change with the times.)

For example, the book quoted above on the subject of top hats was published in 1926. Its author, Lady Troubridge, although comprehensive in her coverage of the etiquette of the day, would have included no comment on a situation in which Her Ladyship found herself recently. She was queuing in the cafeteria of one of the major London art galleries. The woman two places in front of her, in the process of being served, answered her phone and began to talk animatedly. She completely ignored the young man behind the till, not even looking at him when she handed over her money. She managed to waggle a few fingers in thanks as he gave her her change, but went off with her tray without the tiniest blip in her telephone conversation.

It was a typical example of modern rudeness, though to be fair to the woman, she did begin by apologising (to her caller) for having missed a previous call. At least, Her Ladyship acknowledged, she had had the courtesy to turn her phone to silent in the gallery.

Her Ladyship was pondering this when she reached the head of the queue. Just as the same young man was taking her order, one of his colleagues appeared and started talking about what time he was finishing work that evening. Her Ladyship was served without there being a blip in that conversation either.

To Her Ladyships way of thinking, these were both examples of staggering discourtesy. What prevented the woman from saying, Could you hold on a moment? Im just getting some tea or the young man saying to his colleague, Wait a second, please, Im serving this customer? The answer, in both cases, is lack of consideration for the other person involved, which is the simplest and most fundamental definition of bad manners.

Next page