Acknowledgments

THANK YOU to Brandi Bowles and Amy Rost for your expert help getting this science out in the world and making this book a reality.

Thank you to my peer reviewers for your time and neuroscience expertise: Dr. Jessica Couch, Dr. Amy Ryan, Dr. Catherine Croft, and Dr. Carlita Favero, as well as Dr. Shannon Hardie and Dr. Jessica Janiczek.

Mom and Dad, thanks for your support throughout this project.

Seth, thank you for my children and for loving them so much. When we sit back down in Aberystwyth in 20 years, well know we did the absolute best we could do for these kids.

APPENDIX 1

Commonsense Neuroanatomy

Ten Building Blocks to a Human Brain

ITS EASIEST TO think about neuroanatomy as various problems that nature has presented and the ways the human body has solved these problems. Humans need a way of interacting with the world, and to do this we use our brains. To build a human brain, we need ten basic things.

Starting material. Humans have a natural process of carving out a piece of the developing embryo to become the brain and spinal cord, regulated by both genetic cues and signals from surrounding cells. This process, called neurulation, is the defining feature of early development: The embryo starts as a ball. Then as the cells differentiate into neural material, the ball lengthens out, and the future spinal cord appears down the embryos back.

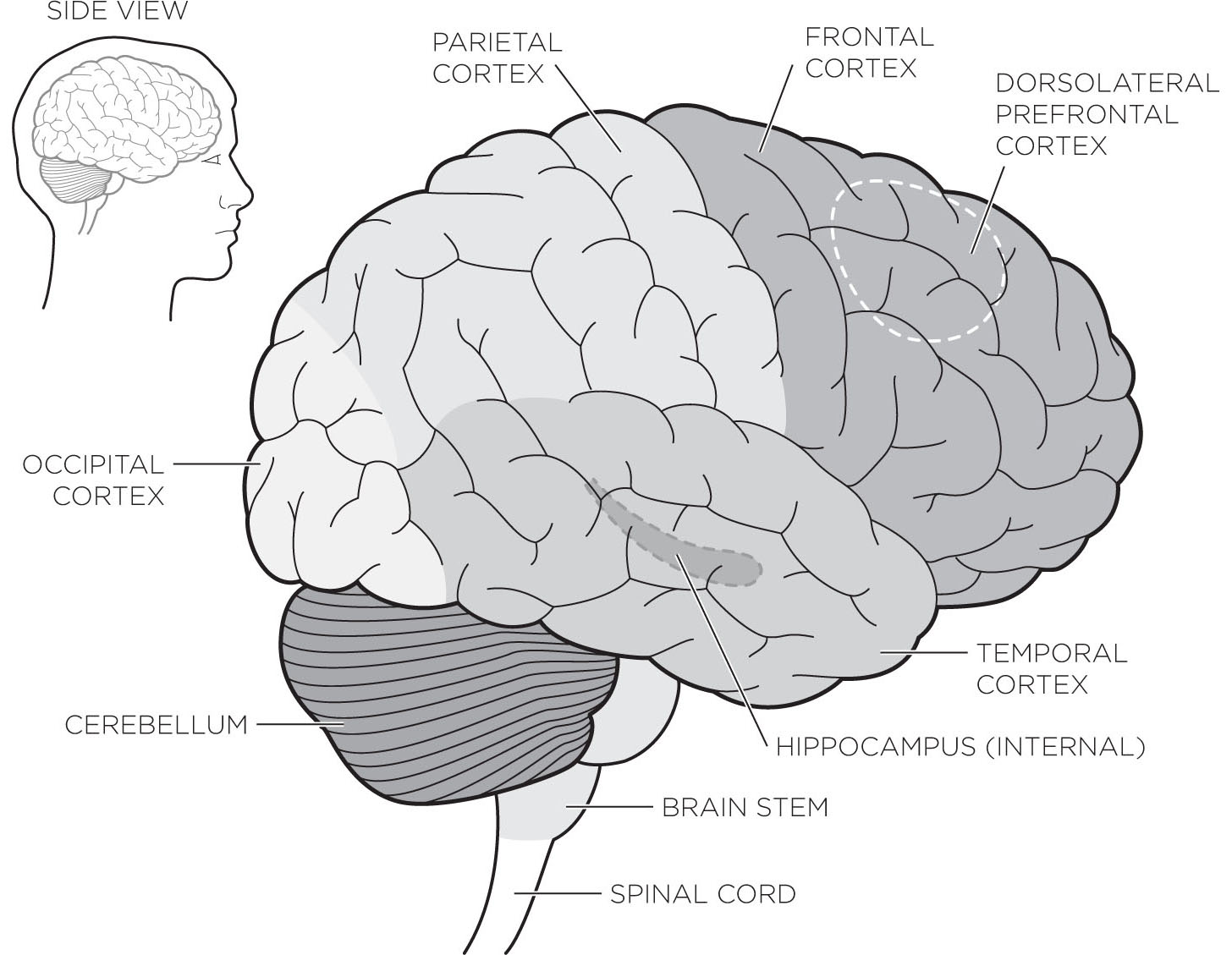

Basic functions: breathing and heartbeat. These unconscious activities are taken care of by the brain stem, the natural progression of your spinal cord as it fans out into your brain. Breathing allows you to pull oxygen into your lungs and then into your bloodstream, and the heartbeat allows you to pump the oxygen and nutrients around your body to your cells. In particular,

The ability to move. Motor control (control over movement) is taken care of mostly by the cerebellum, the small circular structure on the lower part of your brain that almost looks like a miniature brain in itself (see show us that the cerebellum is also involved in whole-brain activities, like cognition and emotion, through intricate feedback loops that link the cerebellum to the rest of the brain and facilitate communication. The simplest explanation of a feedback loop is that its like a circular relay race that never ends, and when you pass the baton, you also offer a bit of running advice to the next runner about how to hone their running skill to be more precise or effective. I tell you something, and in return, you send me back a message that can change the way I tell you things.

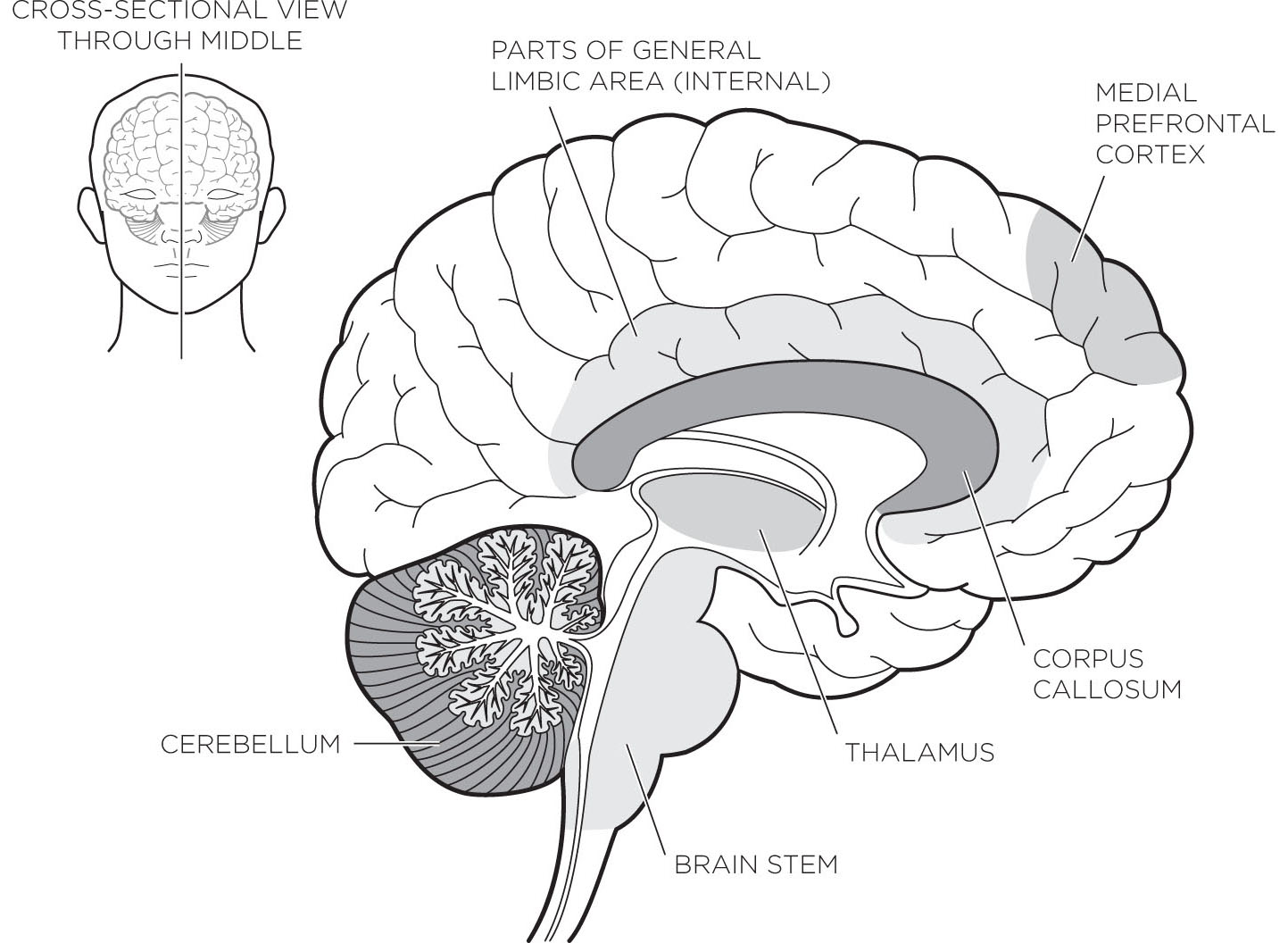

Figure A1.1 The brain and spinal cord make up the central nervous system. The brain stem handles basic functions like heartbeat and breathing, while the cerebellum specializes in balance and movement. The cortex can process and coordinate the activities of the brain stem and the cerebellum.

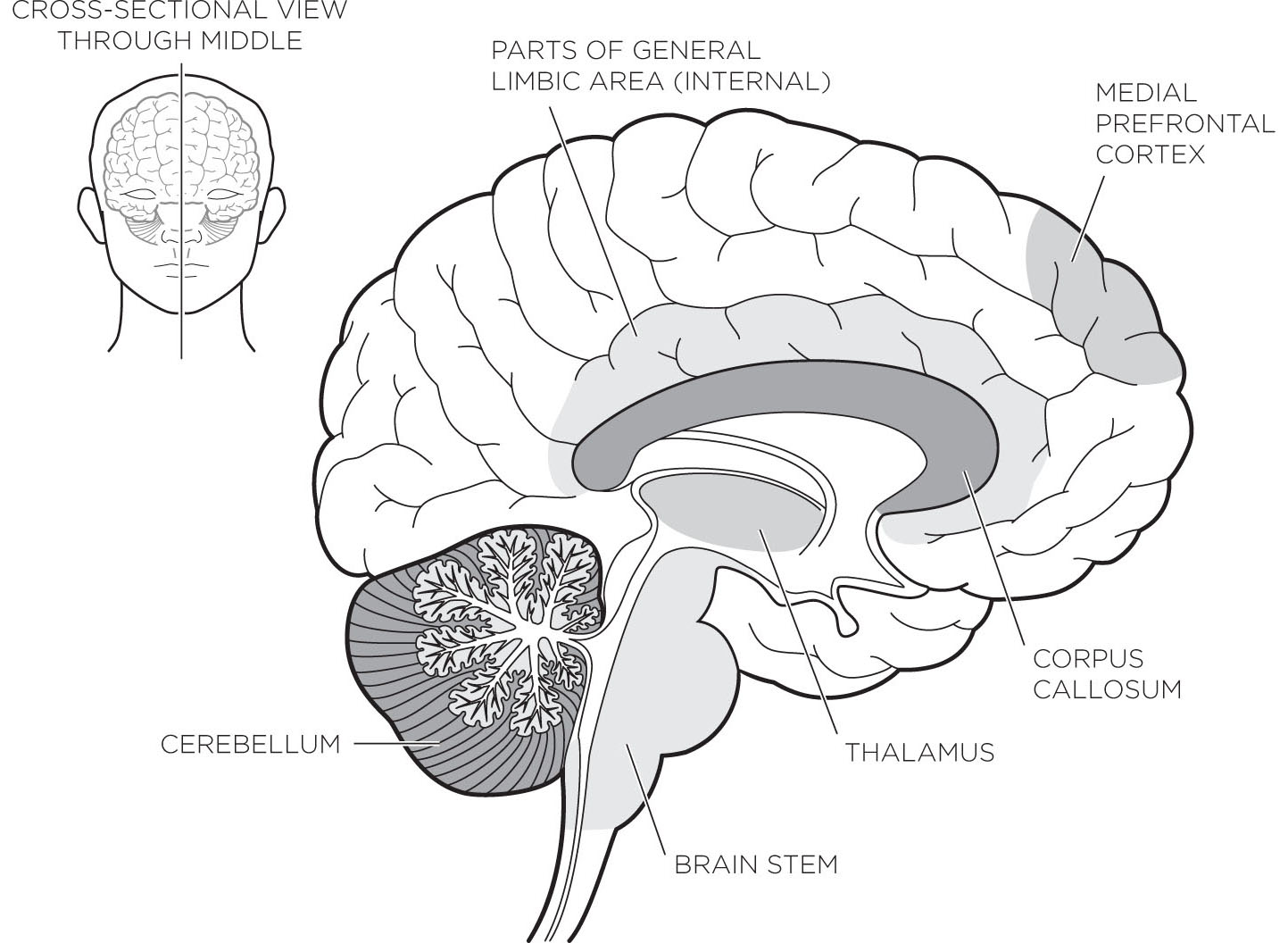

The ability to receive environmental input. Humans, and all animals, do this through sensory input. You have your five basic senses (taste, touch, smell, hearing, and sight), along with a sixth senseproprioception, or the ability to know where your body is in space. The input comes in through a variety of entry points, depending on the sense, is processed in a central location called the thalamus, and is sent to different areas in the cortex to be pondered. For example, touch information can come in from any part of your body, gets passed through the thalamus, and then is processed in the somatosensory (body-sensing) area of the parietal lobe in the cortex (located on the top of your head right below where you would wear a royal crown).

A way of actively sorting through information and deciding what to keep. We cant remember everything we experience each day. So we sort through it all in a very individual way by filtering our environment for things that are important to us: we pay attention to what were interested in, and we remember only what we pay attention to. All memories have meaning for us; otherwise, they wouldnt have been incorporated into our brains. Sometimes meaning is as simple as the items in a scenario that we paid attention tothe items we picked out as being somehow important in a sensory landscape filled with details. We go through a lifelong, daily process of picking out what is important to us in our environment. Other times, a memory has an emotional component to it that cements it in our minds. Sometimes the basic instincts that we have for survival dictate what we remember.

A way to store information. The most well-known memory structure is the hippocampus, which allows short-term memories to be consolidated into long-term memories based on what we pay attention to and rehearse. The hippocampus, along with areas in the cortex, is responsible for memory storage. But there are also many other ways the brain can remember things, such as procedural memory (how you remember to ride a bike) or learning though conditioning (knowing that if you touch a hot stove you will get burned), factual knowledge (remembering the name of your elementary school), and visuospatial memory (knowing the way to get from your house to work). All of this information is stored in different places in the brain.

A way to get the information back out. Memory retrieval is the ability to access information over time. We cant retrieve the information unless we remember it, and we remember it only if weve paid attention to it in the first place. The task of remembering something uses different brain circuits than memory formation does.

The ability to change and adapt. With neuronal communication, the old way of doing things must be discarded at times for a new system, and this is called learning. Learning requires concerted collaboration between multiple brain areas.).

Figure A1.2 We have looked at the higher brain processing centers in the cortex, but we arent able to see many internal brain structures unless we cut the brain in half right down between the eyes and look at it from the side. Viewed this way, you can see that some of the brain areas responsible for gut instincts and emotions, such as the limbic system, are indeed lower in the brain. You can easily see the central thalamus that routes incoming signals to the right cortical areas for processing. But some brain structures remain hidden, such as the hippocampus (responsible for memory formation) and deeper parts of the limbic system. In self-regulation, there is constant interplay between limbic areas and cortical areas.

That is not to say that the amygdalas only role is to modulate fear. It is, like all brain structures, intricately linked to other functions, including regulating memory and social interaction.

The ability to sometimes stop emotional responses. Our first emotional response isnt always our best option, but it makes us undeniably human. Controlling the emotional input coming up from the limbic system is the key to sound judgment, self-control, and what we call mature behavior. This ability is housed in the cortex, particularly the prefrontal cortex, and allows us to modify our actions to fit with what is socially acceptable and in line with our own goal-directed behaviors.

APPENDIX 2

Epigenetics

The Intersection of Nature and Nurture

THE SCIENCE OF INTERACTIONISM, named epigenetics, is an unfolding explanation of how nature and nurture cooperate. Environmental events can turn genes on or off during development and adulthood. Epigenetics is one of the coolest discoveries of the last few decades. Its the idea that nature and nurture can interact with each other within your body. Your experiences can actually change which genes are turned on in your cells. And while your genetic makeup is always the bottom line, if genes arent turned on, then they wont have much effect on you.

Next page