The Dynamite Club

The Dynamite Club

How a Bombing in Fin-de-Sicle Paris Ignited the Age of Modern Terror

John Merriman

With a New Preface

Published with assistance from the Kingsley Trust Association Publication Fund established by the Scroll and Key Society of Yale College.

First published in paperback in 2016 by Yale University Press.

Originally published in hardcover in 2009 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Preface to the Paperback Edition copyright 2016 by John Merriman.

Copyright 2009 by John Merriman.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Book design by Robert Overholtzer.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015951237

ISBN 978-0-300-21792-6 (pbk.: alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

F OR V ICTORIA J OHNSON

Contents

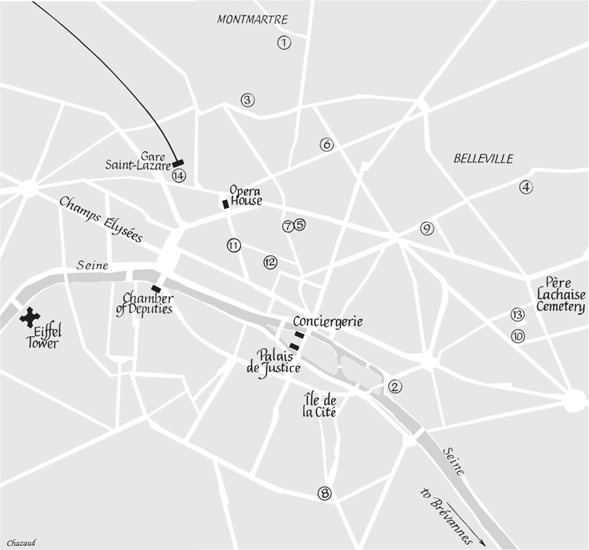

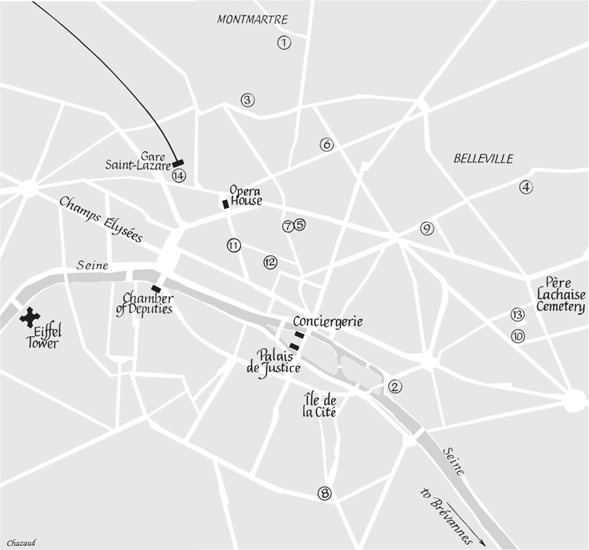

PARIS, 1894

Places Where mile Henry Lived and Worked

1. 101, rue Marcadet

2. 10, boulevard Morland

3. 31, rue Vron

4. Villa Faucheur, 13, rue des Envierges

5. 32, rue du Sentier

6. 5, rue de Rocroy

Other Addresses

7. Constant Martins Shop, 3, rue Joquelet

8. Offices of La Rvolte, 140, rue Mouffetard

9. Salle du Commerce, 94, rue du Faubourg-du-Temple

10. Home of lisa Gauthey, 167, boulevard Voltaire

11. Carmaux Mining Company, 11, avenue de lOpra

12. Police Station, 22, rue des Bons Enfants

13. Execution site, place de la Roquette

14. Caf Terminus, rue Saint-Lazare

Preface to the Paperback Edition

Terrorism Yesterday and Today

On the evening of February 12, 1894, mile Henry, a young anarchist, threw a bomb into the Caf Terminus near the Gare Saint-Lazare in Paris. This was the first modern terrorist act. It represented something new and frightening in the world: an attack on innocent people who just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Henry considered the bourgeois sitting in the Caf Terminus guilty by their very existence.

Henrys bombing differed from violent attacks that had taken place in Russia, for example, where the targets were tsars, governors, or military officials who were, for obvious reasons, identified with the state. For that matter, it was very different from a terrorist attack in our own time on the writers and cartoonists of the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo in Paris on January 7, 2015, which killed eleven people, or the murders in a kosher supermarket on the southern edge of Paris that occurred two days later, in which four Jewish hostages were killed. In another horrendous massacre, in June 2015, a young white supremacist slaughtered nine African Americans in a church in Charleston, South Carolina. These attacks, combined with the mass killings perpetuated by ISIS on behalf of its vision of an Islamic state in Syria and Iraq, and Boko Haram in Africa, tragically remind us that we live in a world increasingly victimized by terrorism.

There are essential differences between nineteenth-century anarchists and todays terrorists. Most obviously, their aims are very different. Anarchist terrorists and it is essential to remember that the vast majority of anarchists were not terrorists wanted to destroy the state. Islamic terrorists today want to impose a strictly fundamentalist religious state. In Iraq, terrorists took advantage of an extremely weak central government; anarchists reacted against states that were becoming ever stronger.

Yet mile Henry and the other anarchist terrorists of the late nineteenth century have some important things in common with the terrorists who plunged hijacked airliners into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001. These commonalities found in the lessons of history and the origins of modern terrorism can help us in deciding how to react to and defend against modern terrorism.

First, in the late 1990s, Osama bin-Laden announced that henceforth he would attack American civilians, not just military targets and leaders, as a way of striking at the U.S. government. Of course civilians had been targeted in such attacks before, but bin-Laden was making it clear that U.S. policy in the Middle East (and elsewhere) justified, in his view, the declaration of a religious war against U.S. civilians, as well as soldiers and political leaders.

Second, both the anarchist terrorists and Islamic fundamentalists today cut across social lines. In France during the early 1890s, French anarchist bombers were social outcasts. Most anarchists in France, Italy, and Spain were artisans or industrial workers, and some in Italy and Spain were peasants. Those who carried out anarchist attacks during this first wave of terrorism were, for the most part, poorly educated. In stark contrast, Henry was a middle-class intellectual. The same is true of the perpetrators of more recent waves of terrorism. Many Russian revolutionaries were of modest social origins, yet both Mikhail Bakunin and Pyotr Kropotkin had backgrounds in the nobility. Bin-Laden was the offspring of an extremely wealthy Saudi family.

Third, mile Henry and his predecessors sought revolutionary immortality. These militants hoped to inspire others with their heroic martyrdom, much like the Japanese kamikaze pilots of World War II and the suicide bombers of today.

Fourth, both sets of terrorists target a powerful enemy, a structure they set out to destroy, while at the same time terrifying, at a minimum, a specific population. Kill one to warn a hundred, goes a Chinese proverb from the sixth century. These enemies tend to be the state and capitalism (along with the pillars that support them, the army and the church) for the anarchists, and the West and particularly the power of the United States for many terrorists today. In both cases, the enemy is seen as oppressing ordinary people, whether by imposing the strictures of government and economic inequality in the late nineteenth century or by posing a threat to Islam, at least as it is defined by fundamentalists.

Fifth, dynamite and bombs became weapons of choice, more accessible ways to penetrate the defenses of well-armed states. Propaganda of the deed anarchists and modern terrorists (and, for that matter, guerrilla fighters in nationalist movements) have found

Sixth, terrorists fervently believe in their ideology, and remain confident that their numbers will grow and that eventually they will win. This gives an apocalyptic, even millenarian, aspect to terrorist movements. Some of the terrorists who carry out violent attacks today, as in the nineteenth century, are young people determined to change the world in a way that suits them. mile Henry was executed at age twenty-one. Youth was characteristic of the Russian Socialist Revolutionary terrorists during the first decade of the twentieth century.