Contents

Guide

ALSO BY PAUL STRATHERN

The Venetians

Death in Florence

The Medici

The Borgias

The chemists are a strange class of mortals, impelled by an almost maniacal impulse to seek their pleasures amongst smoke and vapour, soot and flames, poisons and poverty, yet amongst all these evils I seem to live so sweetly that I would rather die than change places with the King of Persia.

Johann Joachim Becher, Physica Subterranea (1667)

The elementes turned in to themselues, like as whan one tune is chaunged vpon an instrument of musick.

Coverdale Bible, Wisdom, xix, 18

Contents

Credits: AKG London, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9; AKG London/Erich Lessing, 7; Editions Seghers, Paris, 1; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gift, in honor of Everett Fahy, 1977), 8

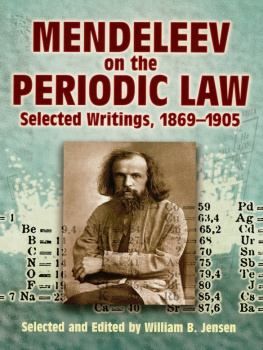

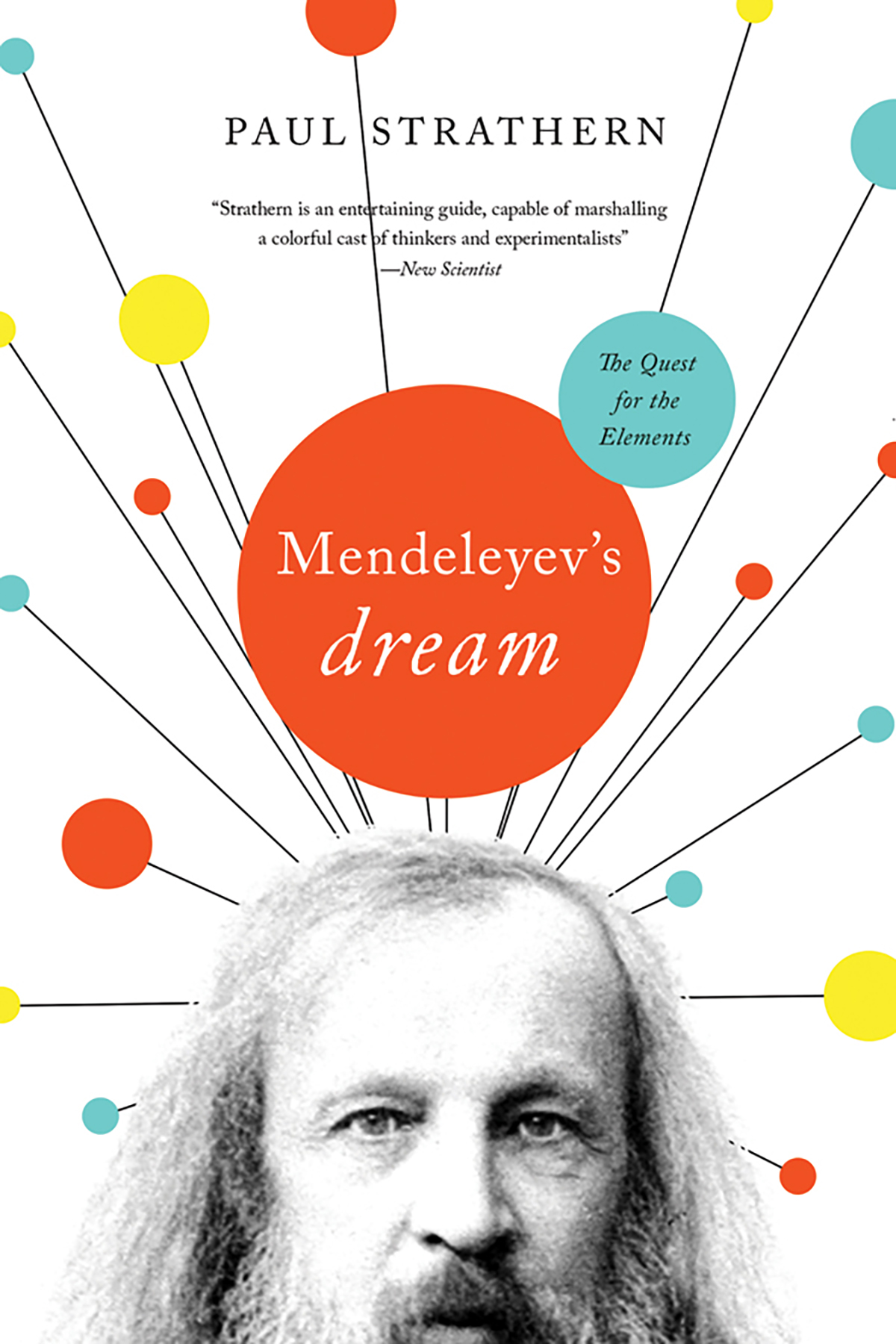

There is a faded photograph of the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleyev at work in St Petersburg, taken some time in the late nineteenth century. It shows a gnomic figure seated at a vast littered desk. Mendeleyev looks not unlike some Siberian shaman transposed to surroundings recognizable as the habitat of the shamans modern successor: the genius-professors study. He has a long white unkempt beard, which ends in three distinct points indicative of obsessively combing fingers during periods of absent-minded pondering. His unkempt white hair trails to his shoulders. Mendeleyev was in the habit of having his hair cut annually. At the onset of the warmer spring weather he would summon a local shepherd, who would attend to this matter with sheep shears. This is the famous shock of hair which once caused Mendeleyev to be described by the Scottish chemist Sir William Ramsay as a peculiar foreigner, every hair of whose head acted in independence of every other. Ramsay supposed Mendeleyev was from Siberia, judging him to be a Kalmuch, or one of those outlandish creatures.

In the photograph Mendeleyev is concentrating over a piece of paper, writing with dip pen held between the very ends of his long fingers. The rest of the wide and irregular desktop is confusion. Pieces of paper upon pieces of paper, a mug on a saucer, a number of instruments of indeterminable purpose and, on shelves beneath the desk, haphazardly stacked files of scientific papers.

Mendeleyev at his desk

At Mendeleyevs back there is a bookcase containing three surprisingly ordered rows of bound volumes. In the midst of these a large labelled key hangs directly above his head like a kind of scientific halo, or exclamation mark. (Eureka!) And above the bookcase the patterned wallpaper of the period is covered with uneven rows of shadowy framed pictures, portraits of the great scientists of the past. From the upper dimness Galileo, Descartes, Newton and Faraday gaze down at the shock-haired figure scribbling away amidst the enveloping disorder.

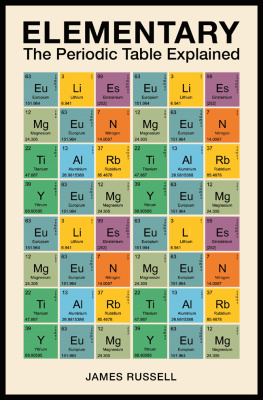

In 1869 Mendeleyev was puzzling over the problem of the chemical elements. They were the alphabet out of which the language of the universe was composed. By this time sixty-three different chemical elements had been discovered. These ranged from copper and gold, which had been known since prehistoric times, to rubidium, which had recently been detected in the atmosphere of the sun. It was known that every one of these elements consisted of different atoms, and that the atoms of each element had their own unique properties. However, some elements had been found to possess vaguely similar properties, enabling them to be classified together in groups.

The atoms which made up the different elements were also known to have different atomic weights. The lightest element was hydrogen, with an atomic weight of 1. The heaviest known element, lead, was thought to have an atomic weight of 207. This meant that the elements could be listed in linear form, according to their ascending atomic weights. Or they could be assembled in groups with similar properties. Several scientists had begun to suspect that there was a link between these two methods of classification some hidden structure upon which all the elements were based.

In the previous decade Darwin had discovered that all life forms progressed by evolution. And two centuries earlier Newton had discovered that the universe worked according to gravity. The chemical elements were the linchpin between the two. The discovery of a structure here would do for chemistry what Newton had done for physics and Darwin for biology. It would reveal the blueprint of the universe.

Mendeleyev was aware of the significance of his search. This could be the first step towards uncovering, in future centuries, the ultimate secret of matter, the pattern upon which life itself was based, and perhaps even the origins of the universe.

Seated at his desk beneath the portraits of the philosophers and the physicists, Mendeleyev continued to ponder this seemingly insoluble problem. The elements had different weights. And they had different properties. You could number them and you could group them. Somehow there just had to be a link between these two patterns.

Mendeleyev was professor of chemistry at St Petersburg University, and was renowned for his encyclopedic knowledge of the elements. He knew them as a headmaster knows his pupils the volatile bad mixers, the bullies, those easily led, the mysterious underachievers and the dangerous ones you have to watch. Yet try though he might, he could still discern no overall guiding principle amidst this whirligig of characteristics. There had to be one somewhere. The scientific universe couldnt just be based on some random collection of unique particles. That would be unscientific.

Mendeleyevs colleague A. A. Inostrantzev, who called in to see him on 17 February 1869, has left an account of this meeting. The account is somewhat imaginative and coloured by hindsight, but supplies some background details. Mendeleyev himself has also contributed various (somewhat differing) accounts of what he was doing and thinking at that time.

Apparently, for three days, almost without cease, Mendeleyev had been racking his brains over the problem of the elements. But he was aware that time was running out. That very day he was scheduled to catch the morning train from Moscow Station to his small country estate in the province of Tver. The professor of chemistry had a meeting with the Voluntary Economic Cooperative of Tver. He was due to address a delegation of local cheese-makers, to advise them on production methods, followed by a three-day tour of inspection of local farms. His wooden travelling trunk had already been packed and was standing in the hall. Through the window of his study the horse-drawn sleigh could be seen waiting in the street, the swaddled driver stamping in the snow, the forlorn nag wheezing white plumes into the frigid air.

But the servants wouldnt have dared to disturb Mendeleyev. His temper was notorious. On occasions he had been known to fly into such a rage that he would literally dance with fury. But what would happen if he missed the train?

The Russian psychologist of scientific discovery B. M. Kedrov, and other commentators on Mendeleyev, have speculated that the pressing thought of the train he was due to catch had an effect on Mendeleyevs mind. It may have been this which induced in him a glide of daydreaming inspiration On the long journeys from St Petersburg to Tver, Mendeleyev would frequently while away the time playing patience. After setting up his wooden trunk between his knees, he would lay the pack face downwards. As the silver birches, the lakes and wooded hills slid past beyond the window, he would begin turning the cards three by three. When he came to the aces he would remove them one after the other, placing each suit in line at the top of the trunk: hearts, spades, diamonds, clubs. Then he would continue turning the cards and one by one they would appear. King on the hearts, Queen on the hearts, King on the diamonds, Jack on the hearts Slowly the suits would begin descending down the trunk. Ten, nine, eight Suits, descending numbers. It was exactly the same as the elements with their groups and ordered atomic numbers!