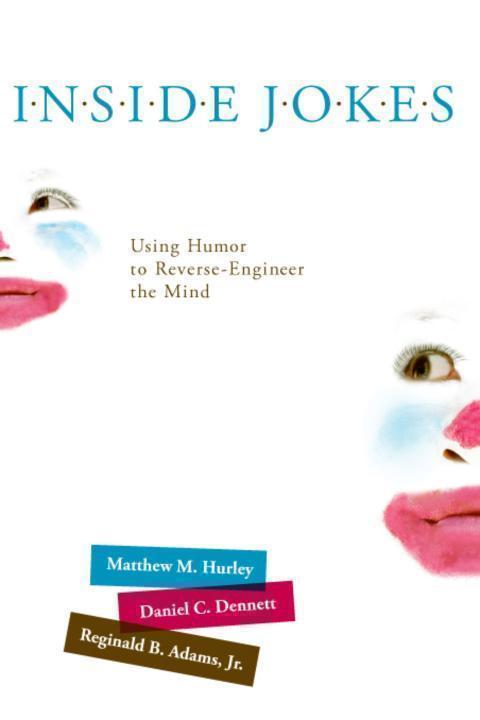

Matthew M. Hurley - Inside Jokes: Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind

Here you can read online Matthew M. Hurley - Inside Jokes: Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 0, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Inside Jokes: Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:0

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Inside Jokes: Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Inside Jokes: Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Inside Jokes: Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Inside Jokes: Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind

Matthew M. Hurley, Daniel C. Dennett, and Reginald B. Adams, Jr.

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

ix

1 1

In April 1975, Martin Gardner reported, in his Scientific American magazine column "Mathematical Games," that a new computer chess program invented at MIT "had established, with a high degree of probability, that pawn to king's rook 4 is a win for White." Tragedy! If this were so, the noble game of chess would be killed for all time, no more challenging than tic-tac-toe. Even if the algorithm purportedly discovered by the program was tediously complicated, something no human chess-player could hope to memorize, the mere knowledge that there was a mindless recipe for winning any game of chess would drain all the glory, all the art, out of the contest. Who would want to devote years to honing skills, enduring grueling tournaments, hunting for exquisite new strategies, all the while knowing that there was an easier way to win, a cheap trick that could not be thwarted? Nobody knows how many readers were taken in, but surely Gardner's unwelcome news struck at least momentary dread in the hearts of some chess-lovers, before they tumbled to the date and chuckled with relief. April Fools'!

Late one night a few years later, the sex researchers William Masters and Virginia Johnson, authors of Human Sexual Response (1966), were analyzing their voluminous data on orgasm and noticed a subtle but striking pattern: they had discovered, to their amazement, that the uttering of a simple verbal formula, a string of words (in any language) that exhibited an arcane pattern based on the Fibonacci series, would bring any normal postpubescent human to orgasm within a minute. They rechecked their data, ran just a few confirmatory experiments, and then ... destroyed their notes, salted their data with misleading falsehoods to conceal the pattern from future eyes, and took a solemn vow not to reveal the secret they had uncovered. Thanks to their heroic sacrifice, sex as we know it lives on.

In early 2010, Hurley, Dennett, and Adams put the finishing touches on their evolutionary/neurocomputational model of humor and wondered if, just possibly, they had cracked the mystery that had baffled intrepid analysts and researchers for several millennia: it seemed they might have not only uncovered the neural mechanisms of humor but in the process devised a foolproof recipe for generating humorous stimuli of all varieties, from slapstick to witty retorts, from dirty jokes to high comedy. Set the dial and turn the crank and out comes Oscar Wilde, Charlie Chaplin, W. C. Fields, P. G. Wodehouse; nudge the dial and turn the crank again and out comes Steve Martin, Jim Carrey, Dave Barry, Gary Larson... Reductionistic science has triumphed again, and humor, as we know it, will soon be dead.

OK, we lied about Masters and Johnson. And we lied about the humor recipe. Not only does the theory in this book not uncover such a recipe, it shows why it is extremely unlikely that anybody-or any bank of computers-will ever find one. Art really is different from science, and comedy is art, like music and, well, art. Art does involve a kind of technology (techne in Greek, technique that one can master), but all the technique in the world only takes the would-be artist partway; our model helps explain why this is so, why the neural mechanisms engaged by humorand they are, at bottom, "just" fantastically complex mechanisms, no wonder tissue involved at all-are quite systematically tamperproof. Nobody can prove that there will never be an algorithm for perfect chess; it is known that chess, which is a finite game, is officially vulnerable to brute-force, exhaustive, algorithmic solution, but it is also clear that no physically possible computer could complete that algorithmic search. That does not rule out the (tragic) possibility that there is a discoverable shortcut. Similarly, nobody can prove that there is no shortcut to humor, but the vast space of possible humor is much, much larger and more complicated than the space of chess, and changing all the time, so nobody should be too worried. Still, we appreciate that many people will confront our book with mixed emotions: curiosity-why on earth is there humor at all? how could it work?competing with the hope that mystery will triumph, that nimble art will scamper out of the path of the lumbering juggernaut of science yet again. We share those mixed emotions and are happy to report that, if we are right, both will be gratified. We will explain why humor exists, how it works in the brain, and why comedy is an art. Let's begin with the first of these questions.

She made them pajamas and bed socks of Swiffer cloth, and the next night while they slept she hid lots of candies around in their rooms, under the beds, under the piles of toys and clothes. In the morning when the children discovered the first of these candies, they went on a gleeful rampage, piling and sorting their belongings in the hunt for all the candies. By noon they were stuffed with candy-and their rooms were as orderly and clean as Martha Stewart's front parlor.

That may be an unlikely story, but we propose that Mother Naturenatural selection-has hit upon much the same trick to get our brains to do all the tedious debugging that they must do if they are to live dangerously with the unruly piles of discoveries and mistakes that we generate in our incessant heuristic search. She cannot just order the brain to do the necessary garbage collection and debugging (the way a computer programmer can simply install subroutines that slavishly take care of this). She has to bribe the brain with pleasure. That is why we experience mirthful delight when we catch ourselves wrong-footed by a concealed inference error. Finding and fixing these time-pressured misleaps would be constantly annoying hard work, if evolution hadn't arranged for it to be fun. This wired-in source of pleasure has then been tickled relentlessly by the supernormal stimuli invented and refined by our comedians and jokesters over the centuries. We have, in fact, become addicted to this endogenous mind candy in much the way long-distance runners become addicted to the endorphins their strenuous efforts pump into their blood streams. Humor, we will try to show, evolved out of a computational problem that arose when our ancestors were furnished with open-ended thinking.

This book grew out of Matthew Hurley's dissertation at Tufts University, completed in 2006, supervised by his two coauthors, Daniel Dennett and Reginald Adams, Jr. Since then it has undergone substantial revisions and enlargements, but the central novelties are Hurley's and the essential details of the theory remain unchanged since its earlier dissertational form. Humor has been a major research interest of Adams for years, and he led the way into the vast literature on humor for his coauthors, correcting myopic interpretations and misapprehensions, and holding their feet to the fire when their ideas were less clear and precise than they should be. For Dennett, this project discharges a promise unkept for almost twenty years. Here, at long last, is "a proper account of laughter" (and amusement) that "moves beyond pure phenomenology" (Consciousness Explained, 1991, pp. 64-66) that he can endorse wholeheartedly.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Inside Jokes: Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind»

Look at similar books to Inside Jokes: Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Inside Jokes: Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.