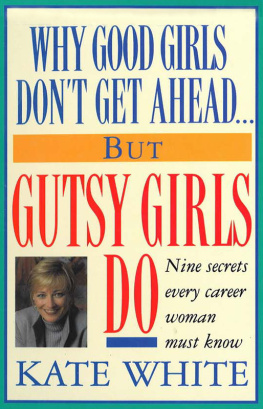

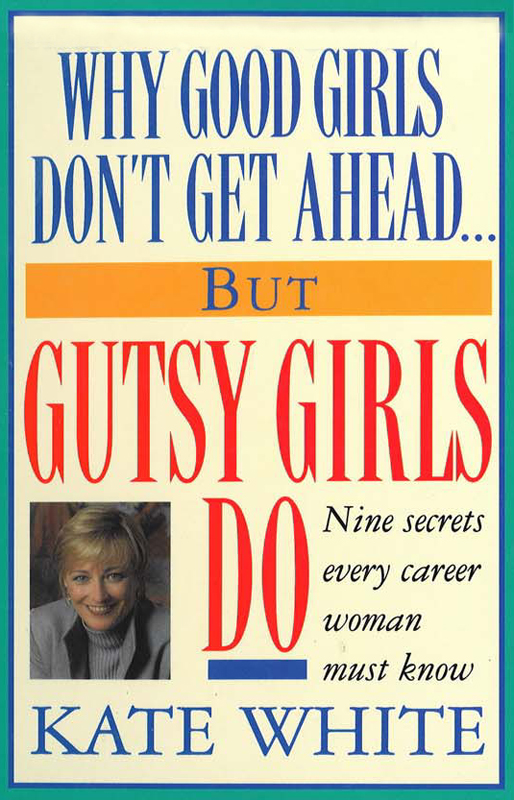

Copyright 1995 by Kate White

All rights reserved

Warner Books, Inc.,

Hachette Book Group,

237 Park Avenue,

New York, NY 10017,

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

A Time Warner Company

The Warner Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

First eBook Edition: December 2008

ISBN: 978-0-446-55479-4

Book design by Georgetta Bell McRcc

To Brad.

I'd like to thank all the gutsy girls who have inspired me throughout my life, including my mom, who always encouraged gutsiness (at thirteen she gave me Bernice Bobs Her Hair to read); my friend Andrea Kaplan, who said, Why don't you turn it into a book?; my fabulous gutsy agent, Sandy Dijkstra; and my wonderful, gutsy publisher, Maureen Egen.

The Myth of the Good Girl

T he day Julia Roberts's publicist telephoned my office and told me that Julia wondered what I had against her. I began to make an interesting discovery about myselfthough I didn't realize it at the time.

First, let me give you the background on how Hollywood's hottest star had come to hold me in the same regard she had for the stripper Kiefer Sutherland was dating during their engagement About a year before, as the editor-in-chief of McCall's, I'd commissioned an unauthorized cover story on Roberts, focusing on her mysterious hiatus from movies after she'd called off her wedding to Sutherland. It had sold like crazy on the newsstands Now, the first rule of magazine newsstand sales is that if something works, you do it againand that was my game plan exactly. The publicist had been furious about our first effort, and as soon as she got wind of the fact that we were planning yet another unauthorized cover story on her star client, she called me to protest. She said angrily that she'd always assumed that McCall's had high journalistic standards and wouldn't stoop to publishing a celebrity profile without interviewing the subject. She claimed that Julia had even asked her, Does the editor of McCall's have something against me?

Though most of our cover stories were interviews with celebrities, occasionally, when we were turned down by someone (as we had been by Roberts), we'd report the story using a variety of other sources. You'd be surprised at how many friends and relatives are willing to gab, though you also can discover that people have been warned to keep their mouths shut. In this particular case, the publicist was telling everyone, right down to the dolly grip operators on Julia's latest movie, not to talk to us, and so far this had resulted in a severe dearth of dirt. When I'd checked on the progress of the story one day, the researcher had looked up woefully from her desk and announced that the only new information she had was the fact that Roberts's nickname in high school supposedly had been Hot Pants. Oh great, I thought. There was cover line potential (IS JULIA HAUNTED BY HER STEAMY PAST?), but the article would be one paragraph long.

Despite such roadblocks, I knew that eventually we'd end up with something. In the long run, this type of story often turns out to be the juiciest and most fun to work on because you've got to be more creative and resourceful.

Unfortunately Roberts and her publicist weren't seeing the fun in all of it. This was hardly the first time I'd had trouble with a cover subject. I once had to kill a cover story on a television star because the photographs came back making her look about as glamorous as a spokesperson for National Tartar Control Month. We heard from the star's publicist that she was very, very miffed. But this was the first time that I had been chewed out personally on the phone. Several days after the conversation with the publicist, I got a letter from her reiterating her annoyance. It was clear that Julia would certainly never agree to an interview with McCall's, and neither would any of the publicist's other clients. In fact, it almost sounded as if she was going to warn off all of Hollywood. Did this mean that I'd better get Marie Osmond and ha Zadora on the phone fast because they'd be the only women I'd be able to recruit for a cover?

As I was packing up to leave the office that night, my assistant looked up at me and asked, Does it bother you to get a letter like that? Aren't you worried that she might really do something?

No, it doesn't bother me, I laughed. And I meant it.

A few years before it would have bothered me. In fact, it might have even tortured me to know that someone was really mad over something I'd done and might say rotten things about me to other people. I liked being liked and hated not being likedand I probably would have walked around for the next few days with a sense of dread, like the kind you experience when you are in the Federal Witness Protection Program. But those feelings just didn't happen anymore Somewhere along the way I had stopped worrying about what people thought about me.

MY MOMENT OF DISCOVERY

About a week later, a friend of mine in the company steamed into my office and handed me an article from the trade magazine Executive Female called Why It Doesn't Pay to Be a Good Girl. The piece had been written by a woman who once had worked for me at another magazine and I assumed that was why my friend was showing it to me. As I glanced through it, however. I discovered, much to my amazement, that I was the focus of the story.

In the article the writer described herself as the quintessential good girl, someone who had always done what she was told, tried to make everyone like her, and taken on as much work as possible. She'd assumed that one day she'd be rewarded for such noble efforts. But much to her shock she'd seen many of the spoils she thought she deserved go to women like me. The author claimed I was the antithesis of a good girl, someone who broke the rules, didn't give a damn what people thought, made quick, bold decisions, and delegated all the grunt work to others (keeping control of the delicious, exciting stuff for myself). She said, with regret, that I had become her role model.

At first I thought, She's got it all wrong. I'd certainly heard psychologists talk about the concept of the good girl, the kind of woman who worries so much about pleasing other people that she neglects her own needs. Years before, I'd even written an article for Mademoiselle on the subject. If anyone had asked, however, I probably would have said automatically that I was a good girl myself.

But the more I considered it, the more I could see for certain that I was not a good girl. I was decisive, almost fearless, and I didn't spend time worrying about other people's opinions of me. That, after all, was why I hadn't agonized over the comments of Julia Roberts's publicist. I also realized that it was the reason for much of the professional success I'd had in the past few years.

Once, I had been a good girl. In fact, it's safe to say I'd been one for a huge chunk of my life. But over timeand especially during the past six yearsI had changed rather drastically. What was I now? There seemed to be only one phrase for it:

I had become a gutsy girl.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOU FOR A MINUTE

If you bought this book, you probably responded on a gut level to the words good girl in the title. It's an expression that most women react to viscerally because we heard it over and over as we were growing up. Every time we jumped in a puddle with our party shoes on or cut off our doll's hair with nail scissors or blew bubbles into our milk or clobbered our little brother with his own weapon after he'd repeatedly tortured us, we were told. Be a good girl, or Good girls don't do that.